A real-life Simmba! It’s a moniker Cyberabad commissioner of police V.C. Sajjanar appears to have earned from twitterati after the Telangana police recently gunned down four men accused of raping and killing a woman veterinary doctor.

From <em>Inquilab</em> To <em>Simmba</em>, How Bollywood Has Glorified Extra-Judicial Killings As A Heroic Act

Cyberabad Commissioner of Police VC Sajjanar, who gunned down four men accused of raping and killing a woman veterinary doctor in Hyderabad, won kudos for his Bollywood-styled act of a 'supercop'

Minutes after news broke of the ‘encounter’, the 1996-batch IPS officer was hailed by many on social media platforms as a ‘supercop’ for having executed a Simmba-like operation against the alleged rapist-killers within days of the ghastly crime. Some went so far as to suggest that the police might have watched the movie before venturing out.

Were similarities between the reel and the real so acute? In Simmba, the leading man—a policeman played by Ranveer Singh—kills a rape accused in custody, ignoring the justice delivery system. The Telangana cops have been charged with having committed a similar offence. The jury is still out on it being a case of life imitating art, but there is no denying the fact that Bollywood has unabashedly glorified extra-judicial killings as a macho, heroic, therefore necessary, way of dispensing speedy justice that the ‘system’ unaccountably tarries over. From Inquilab (1984) and Gangaajal (2003) to Ab Tak Chhappan (2004) and Simmba (2018), many a movie has projected law-breaking protagonists as heroes waging a lonely fight against an unjust system from within.

But can a movie like Simmba, or for that matter, Dabangg (2010) or Singham (2012), where unlawful acts of a trigger-happy cop are exalted, influence a real-life policeman into taking the law into his own hands? Not on your life, avers film-maker Maann Singh Deep. “Real cops do not get inspired by their reel counterparts,” says Deep, who has produced movies like Gunehgaar (1995), Jurmana (1996) and Raja Bhaiya (2003). “On the contrary, producers, directors and screenwriters get ideas from real-life incidents in a policeman’s life.”

Deep, who claims to have had a close association with so-called encounter specialists of the Mumbai police, says his contacts have often told him amazing stories about the force’s anti-criminal activities. “I was often inspired to incorporate those incidents in the scripts of my films,” he says. “But never did I hear of any policeman getting swayed by anything that he might have seen in a film.”

Deep admits that audiences are influenced by certain aspects, like fashion adopted by top stars, but for sensitive subjects like police encounters, directors themselves draw inspiration from real incidents, then take cinematic liberties.

Screenwriter Rajat Aroraa concurs. “What is shown onscreen is more often than not a reflection of what is happening in society,” says Aroraa, who has scripted blockbusters like Once Upon A Time in Mumbaai (2010), The Dirty Picture (2011) and Kick (2014). “For instance, Prakash Jha’s Gangaajal (2003) was based on a true incident (Bhagalpur blindings). But no such incident took place after the film’s release.”

According to Aroraa, cinema and society are like shadows of one other. “The Hyderabad police encounter is not the first of its kind in India. Mumbai witnessed quite a few in the past, which later inspired movies,” he points out.

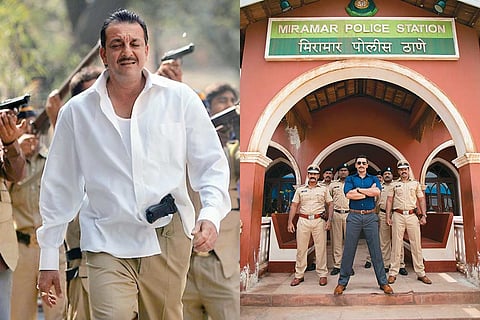

Sanjay Dutt in Shootout at Lokhanwala; right, Ranveer in Simmba.

Just like the Hollywood trend of the antagonistic cop was established by Dirty Harry (1971), starring Clint Eastwood, the Bollywood cop movie took off after the mega success of Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer (1973), which cemented Amitabh Bachchan’s enduring angry-man image. Its success led almost all leading actors of the time to play upright policemen. The newish trend, revolving around a tough hero such as a policeman (often in dark shades) who has no qualms about staging a fake encounter to kill outlaws, came about with the rise of gangster flicks at the turn of the millennium. In the next two decades, films like Encounter (2002), Risk (2007), Shagird (2011), Department (2012,) Shootout at Lokhandwala (2007) and Shootout at Wadala (2013) tackled extra-judicial killings as their central or sub-plots. The most popular was the Nana Patekar-starrer Ab Tak Chhappan, which was based on Daya Nayak, the controversial encounter specialist of the Mumbai police. In the past decade, stars like Salman Khan, Ajay Devgn and Ranveer Singh starred in big-ticket extravaganzas such as Dabangg, Singham and Simmba, where they took out outlaws with impunity despite being custodians of law.

National Award-winning writer Vinod Anupam believes that movies on extra-judicial killings are merely an extension of Bollywood’s penchant for anti-establishment cinema. “Content-wise, Indian cinema does not appear to be enamoured of democratic traditions. It always targets the weakest link, be it the legislature, the judiciary or the executive,” he says. “Here, cinema caters to average people. If they believe that a person accused of committing a heinous crime should be shot dead, the film tries to show exactly that. In no way does it try to challenge the intellect of audiences.”

Cinema, therefore, becomes the voice of people who are dissatisfied with the existing system, Anupam states. “Everybody likes to see justice being delivered instantly. Even in Rang De Basanti (2006), the only solution offered to end corruption is to shoot the culprit even if he is the defence minister,” he says. “Way back in the 1980s, in the Amitabh Bachchchan-starrer Inquilab, the protagonist enters the Vidhan Sabha to open fire at corrupt politicians.”

Social scientist Gyandeo Mani Tripathi points out that cinema brings to the fore the latent aspirations, desires and feelings of audiences. “Audiences clap when they see something which they are not capable of doing,” he says. “That is why filmmakers play to the gallery.”

Tripathi says that glorification of encounter killings onscreen does influence moviegoers, especially youngsters. “It may even influence policemen.... But it will not be proper to blame cinema for any Hyderabad-like incident. Cinema, after all, plays a tiny part in our lives.”

As of now, there is no let-up in Bollywood’s interest in the good cop-bad cop trope. Rani Mukherjee is playing police superintendent Shivani Shivajirao, out to get a serial rapist in Mardaani 2, which is releasing next week. A week later, Salman Khan will be back with Dabangg 3, where he reprises his playful ‘policewala goonda’, Chulbul Pandey. Akshay Kumar returns early next year as a cop in Sooryavanshi. These cops will not play by the virtuous rulebook as their yesteryear’s counterpart. They would rather bare their murky souls in the pursuit of justice. It is only a matter of time when a movie based on the Hyderabad encounter will hit the screen.