Powlasthya kula shiromani, Shiva charan is sharana bhaktagrani

Did Raavan Really Have 11 Heads?

Inspired by the 12th-century Kamba Ramayanam by Tamil poet Kamban, Valmiki’s Ramayana and Shashi Raj Kavoor’s play Ekadashanana, a dance performance boldly challenges the traditional portrayal of Raavan.

Saamagana sushiromani, athmalinga sambhavita mahimagrani

Dhasha Disha Digvijaya maanitha, Dashagreeva parishobitha

Chathurveda parangata, Chaduranga virajit

Kailasa giri dharana buja Shekara

Shree Shree Shree Lankadipati Raveneshwara

(The best in the clan of Pulasta, the greatest devotee of Shiva

Maestro of Samaveda, the one who got the Atmalinga

Conqueror of all directions, the one who flows with 10 heads

Scholar of the four Vedas, the winner of battles

The one who lifted the Kailasa mountain on his shoulders

Victory to the king of Lanka—Ravaneshwara)

Popularly regarded in most parts of India as a demon god with 10 heads, Kannadiga artiste Surya Rao chooses the untold tale of Raavan’s 11th head, to lead the opening sequence of his enthralling multimedia format dance-drama production ‘Ravana: The Untold Story of the Eleventh Head’.

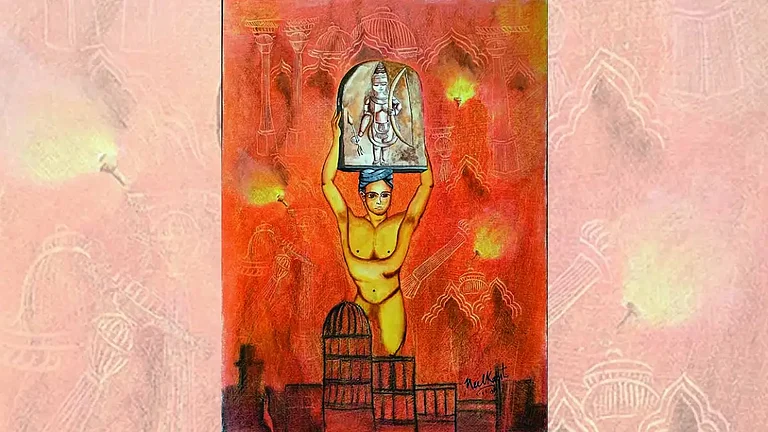

Inspired by the 12th-century Kamba Ramayanam by Tamil poet Kamban, Valmiki’s Ramayana and Shashi Raj Kavoor’s play Ekadashanana, this performance boldly challenges the traditional portrayal of Raavan. It provokes curiosity about the mysterious 11th head of this multifaceted figure while also extolling the protagonist’s virtues.

But is there really an untold story about Raavan’s 11th head, concealed in lesser-known scriptures or obscure folk tales? The audience in a tony, suburban Mumbai theatre on a rainy Sunday evening eagerly awaits with bated breath, for an onstage revelation to this almost mystical question.

In the solo 40-minute act blended with elements from traditional dance forms, namely Kuchipudi, Bharatnatyam and Yakshagana, Rao plays the protagonist, Raavan, spending his last night on earth after an embittered slugfest on the battlefield with Rama. Standing at the gates of Vaikuntha, Raavan contemplates the defining moments of his life before embarking on to his final avatar. Conflicting voices echo in his mind: one urges him to fight Ram, another advocates surrendering for a chance at swarga loka (heaven), while a third shames him for the bloodshed of his own kin. Amidst this din, he reflects on the years he has spent on Earth.

He recalls meeting Ram, his ultimate foe—for whom he even conducts a yagna in Lanka, despite being fully aware that Ram has arrived to slay him. As an ardent devotee of Shiva and the only Brahmin scholar in Lanka, Raavan officiates the ceremony, tying a holy thread to Ram’s wrist and granting him the auspicious moment to start the war, marking the arrival of his own death. He reminisces about his passion for music and his invention, the Rudra Veena, that he devised to please Lord Shiva. The melodies drawn from the veena remind him of his courtship with Mandodari, a nymph cursed to live as a frog until he kissed her. He also thinks of his sister Shurpanakha, now disfigured and humiliated, and the pain that fuelled his vow for vengeance against the humiliation.

In Hindu mythology, Raavan is killed annually on Vijayadashmi or Dussehra, symbolising the triumph of good over evil. Traditionally portrayed as a villain in Tulsidas’s Ramayana and Ramanand Sagar’s popular televised version of the epic, he is often overshadowed by Ram’s calm elegance. However, Rao’s performance au contraire offers a fresh perspective, introducing Sundar Raavan—a handsome, majestic, noble king. With a beatific smile and powerful, controlled dance moves, Rao brings to life a multifaceted Raavan, as a learned scholar, musician, lover and warrior.

“Ram became a God after killing Raavan. If there was no Raavan, there would be no Ram,” says Rao with a twinkle in his eye, while explaining the philosophy behind the play.

Inspired by Yakshagana folk theatre, which he began performing at the age of four in Karnataka’s Hubli district, Rao, alongside scriptwriter Keerthi Kumar, presents a captivating interpretation of Raavan as a young, valorous yet flawed hero. Yakshagana, originating around the 15th century among farming communities in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, combines song, classical dance, costumes and improvised dialogue. Traditionally performed from November to May, these nightlong shows depict various episodes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata and other mythologies.

Rao has always been fascinated by Raavan’s character, which has lingered in his mind since childhood, drawn by the large headgear, colourful makeup and elaborate costume. “I used to imagine how a man could walk with 10 heads,” says Rao. It was only later that his mother and grandmothers revealed the mystery, explaining that the 10 heads are figurative, symbolising the diverse traits of 10 individuals within a single body.

“He had a multifaceted personality and had several great qualities. He was not just an evil demon, who abducted Sita. He was a master in all the 72 art forms; he was a physician and knew about medicine. The various perspectives in scriptures and folk tales have shaped our thoughts in bringing this production on stage,” adds Kumar.

Yakshagana scholars emphasise that performers of the folk art recreate stories rather than simply translating them into literary forms of stories and songs. This approach leads to new, more intriguing interpretations of characters like Raavan, Shurpanakha, Vaali, Kamsa and Duryodhana, typically seen as wicked. In Yakshagana, these figures are depicted as flawed humans facing curses, often portrayed as pratinayaks or anti-heroes. In their narratives, Raavan often emerges as a feminist and champion of the downtrodden, while Shurpanakha advocates for women’s liberation and Vaali is celebrated as the protector of forests.

“Yakshagana is a dynamic form of a living theatre. Here, actors have the liberty to establish a character with intelligence through debate and narration,” says veteran artist and scholar Malpe Laxminarayana Samaga. “This allows actors to impersonate characters with intelligence and minds of their own, including the ones with negative aspects.”

In Yakshagana, characters from the Mahabharata and Ramayana are portrayed in nuanced shades, reflecting satvic, rajasik and tamsik gunas (pure, energetic and vengeful values). Some exhibit more goodness than evil, while others embody a worldly or spiritual perspective, according to Kumar. Demons and asuras are seen not as purely evil, but as cursed souls repenting for past misdeeds.

This tradition of depicting anti-heroes incorporates virodh bhakti or something that challenges the hero’s inherent divinity. Notably, Raavan experiences a moment of divine revelation on the battlefield when Ram reveals his true form as Vishnu. At this pivotal moment, Raavan bows in reverence to Vishnu’s Vishvaroopa, acknowledging the divine grace, yet chooses to fight when Ram returns to his human form.

“Ultimately, the picture we get is that Raavan is not completely wicked. Yakshagana, like Shakespearean literature, port rays characters with a little bit of goodness and wickedness. No human is completely bad or good,” says Samaga.

He further surmises that philosophically, Yakshagana showcases the large-heartedness and open thinking prevalent in Indian mythology, which pushes us to look for goodness even in the most evil people. “After watching Yakshagana performance, the narration makes many people reconsider Raavan as a hero,” he says with a smile.

At the end of Rao’s spellbinding performance, the audience remains seated, eagerly anticipating the revelation about the 11th head. A moment of epiphany strikes the theatre as Rao and Kumar reveal that the 11th head represents “Raavan’s inner conscience”. Through this head, the protagonist articulates his actions and justifies his decision to confront Ram, leaving the audience in awe.

Could it be that Raavan abducts Sita not out of lust but to lure Ram to Lanka, fully aware that his death is destined at Ram’s hands? The murmurs in the audience spark various interpretations. And yet, there is one particularly loud confession from the audience, which is met with thunderous applause. It is a voice that confesses: “It has made us respect Raavan.”