Full text of the 19th Justice Sunanda Bhandare Memorial Lecture —Representation of Women in Indian Cinema and Beyond— by Sharmila Tagore at the India International Centre (IIC) on November 27, 2013

'Popular Stereotyping'

Time and again, our films underline the supremacy of man. Modernity is reduced to a matter of packaging. A modern woman is defined by her westernized attire. She looks modern but when it comes to making informed choices, she chooses the conventional.

Even 65 years after our independence, we find that India’s progress towards establishing an equitable society has been slow and disappointing. Discrimination against women thrives and cuts across religion, caste, rich, poor, urban-rural divides. Today, in 2013, and so many legal provisions later, things are arguably better than before; yet certain things remain unchanged. Secure in their solid economic and social foundation, men are men, and we are the other. Today, women realize that unless certain fundamental issues that affect gender equality and justice are addressed, women’s empowerment will remain at the level of rhetoric.

While education, employment opportunities and social networks have given some women like us a voice, many women still continue to suffer injustice silently in the name of family, honour, tradition, religion, culture and community. So ingrained are certain modes of thinking that bias is not even perceived as bias, not even by the women themselves.

As Uma Chakravarti says, all of us carry within us a sense of the past which we have absorbed over the years from mythology, popular beliefs, tales of heroism, folklore and oral history. This medley of ideas, which is patriarchal in nature, has a strong hold on our collective consciousness and forms the basis of our understanding of the status of women in the past. These perceptions are also continuously brought forward and constituted and reconstituted anew. Centuries of imbibing such ideas probably resulted in son preference in the Indian family, particularly in the north. While reviewing the book Religion, Patriarchy and Capitalism, Rajesh Komath says, and I quote,

‘This entrenched mindset furthers the idea of female infanticide, considering girls as an economic burden. The dowry system and the notion of the girl child belonging to her husband (a kind of tying up of a woman to a man) treat women as an expensive commodity in her own family. Even at a time of societal progress in terms of science and technology, there seems to be no real benefit to the woman. Rather, what is observed is a reverse societal dimension.’

Traditionally, we as a nation have tended to view a woman either as devi (goddess) or as property of man but never as an equal. Treating a woman as a devi is pretty ingenious because then she has to be on a pedestal and conduct herself according to the noble ideals a patriarchal society has set for her. Women seem to like being on that pedestal and despite their inner urges cling to this ideal of being perfect at great personal cost. So, in spite of the outstanding advancement of both men and women, mindsets have been slow to change. And these mindsets have influenced our cultural spheres, and have been celebrated in festivals like karva chauth, raksha bandhan, Shiv ratri, appealing to a man’s ego in protecting and indulging the women in his family. So it is not surprising that a mass, popular, highly visible media like cinema, particularly Hindi cinema, has perpetuated these cultural myths.

Apur Sansar

Since then, societal attitudes towards films have changed dramatically. Today we are the largest producers of films in the world. Our films have made undeniable progress in technical terms, in production values, but when it comes to the portrayal of women I feel the changes are merely cosmetic. Sometimes I think that the phrase ‘the more things change the more they remain the same’ was coined precisely for this. Films continue to brandish an image of women which is largely decorative and secondary. Of course, there are exceptions. Parallel cinema, some regional cinema presents women in an entirely different, more equal, and more realistic light. But it is mainstream Hindi cinema which is the dominant film industry in the country. It both reflects and influences social and cultural mores. So, in this talk I shall focus largely on this particular stream.

The 1930s was a progressive era when it came to women in cinema. We had Devika Rani. I cannot think of another comparable woman producer in the eighty years since. Fatima Begum was the first Indian woman director who made Bulbul-e-Paristan. There was Durga Khote, a Brahmin, who made the extraordinary decision of acting in films at a time when it was considered a dubious profession. In Mary Evans, popularly known as Fearless Nadia, we had a feminist much before the term gained currency.

In the 1940s, with the end of the studio era and the influx of those looking for quick profits without any commitment to quality, the ideological moorings of the thirties cinema were undone. Cinema changed from being a social forum to a commercial industry where entertainment was paramount. As men made up the majority of viewers, the economics of film-making became increasingly skewed in their favour. Further, with almost the entire spectrum of film-makers also being men, women came to be depicted in a way that would appeal to the masculine segment of the audience and reinforce a rather chauvinistic attitude towards women and their place in family and society.

Still, the 1950s retained some sensibility in the depiction of women in cinema. Bimal Roy had strong and realistic women characters in his films Sujata and Bandini. In Mother India, Nargis essayed what is probably the most iconic female role in the history of Indian cinema, while Mughal-e-Azam had another memorable woman, Madhubala, in the lead role.

Mughal-e-Azam

‘Her virtue is in being the good mother, wife, sister—a set of essential roles a woman has to play—which is a terrible kind of oppression; a glorification not allowing the woman any choice.’

The decades after the 1950s have been particularly disappointing, with women being increasingly relegated to playing glamorous sweethearts who exist only for the amorous pleasure of the heroes and who are totally dependent on the male species to protect them and provide them with a sense of security and fulfilment. Things reached a nadir in the 1980s, a decade which saw unimaginable violence being perpetrated on women in films to such an extent that the inconsequential frivolity of the 1960s and 1970s seemed welcome. In the early sixties, two films, Guide and Sahib Biwi Aur Ghulam, shine brilliantly. Both had remarkable women protagonists.

Of course, there were sensible directors like Gulzar and Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterjee whose portrayal of women were refreshingly different. The films of Shyam Benegal, Ankur, Bhumika and many others, have well-written female characters. But these were in the nature of exceptions and were no match for the huge blockbusters of mainstream cinema which kept reinforcing stereotypes of women as young, beautiful, innocent yet sexy, pliable, obedient, always placing her family and others before herself. Popular cinema, as Maithili Rao says, endorses the norm that ‘A woman’s place is at home. Her interest is best served by directing all her energies and intellect in finding a man and keeping him. Marriage is her passport to life and she is happy only when she is brought into the fold of marriage and motherhood and submits to the norms of society.’

These are the clichés that get reflected in and reinforced through our movies. Reason and emotion are considered incompatible. The first is associated with men and is valued positively and the second with women and is viewed negatively. Powerful decision-making roles go to men and goody-goody ones to women. A girl seldom gets to live life on her own terms. She has to be monitored and patrolled for her own good. Khap panchayats today have taken this to another level in the way they dictate how their women should behave. No law seems to apply to them. It is dinned into a woman that her actions affect the honour of her family and community. Even at work she faces the same attitude. A woman who questions the system is seen as ‘difficult’. Her need to find redressal is often overshadowed by the collective concern of preserving the honour of the institution. Complaints pertaining to sexual harassment are often not reported or are hushed up. It is not surprising then that the woman often absorbs and internalizes what society imposes and dictates and seeks her definition in relation to men. It is very difficult, if not impossible, for her to break out of this patriarchal set-up.

The typecasting begins from childhood. Little boys are naughty, little girls are pretty. Boys are brave, girls are good. Women are caregivers and always subordinate to men. I remember telling my three-year-old son a bedtime story where I rescue him from a crocodile-infested river. His cynical response was, ‘You can’t save me, you have no muscles, you are not strong. I love Abba because he is strong and I love you because you are good.’ Our films reinforce the same ideas. They also reduce modernity to a matter of packaging. A modern woman is defined by her westernized attire. She looks modern but when it comes to making informed choices, she chooses the conventional. The moment she is to be presented to society for marriage, her sartorial style undergoes a complete traditional overhaul, because now she is expected to become part of the collective, her individuality discarded for the sake of the community. It is implied that the modern woman who asserts herself and her independence can never bring happiness to anyone, nor find happiness herself. Often, in the first half of a film a lot of new and dynamic ideas are introduced, only to be diluted and compromised in the second half.

Kahaani

We have recently celebrated the woman in films like The Dirty Picture and Kahaani, but come to think of it, with the protagonist becoming an alcoholic and committing suicide in The Dirty Picture, wasn’t the audience being invited to view the character as a victim? Or for that matter the protagonist in Kahaani, who says at the end that the only time she felt fulfilled and complete is when she was pretending to be carrying a child. Where was the need for the scene? Unless this and Amitabh Bachchan’s voice-over likening her to Goddess Durga—again a traditional role-play enforced on a woman for centuries were the director’s insurance in the face of what till then had been decidedly a strong and unfeminine protagonist.

Another example of popular stereotyping is seen in the near-complete absence of working women in our mainstream cinema. In this aspect too, the 1950s—with films like Awara, Shri 420, Kaagaz Ke Phool appear progressive vis-à-vis what followed. Even in the films of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, who made such women-centric films as Anupama, Anuradha, Guddi and Khoobsurat, women seldom ventured out to work, barring of course Abhimaan which was a critique of male chauvinism. It can be argued that in the 1960s and 1970s, when Mukherjee made his films, although we had a powerful woman prime minister at the time, women rarely went out to work.

Applying the same logic, women’s roles in film should have changed in the 1990s, a period which saw women take to the workplace in large numbers. But a look at some of the films that defined the decade paints a different picture. In an era when more and more women ventured out of their homes to build a career, the more women in cinema stayed at home. The leading ladies in films like Maine Pyar Kiya, Hum Aapke Hai Koun, and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jaayenge, are all quite content to wait for their Prince Charming to come and carry them off to the fairy land of marital bliss. The common thread—running through all these films—is that a woman’s place is in her home, looking after her man, because it is the man who is traditionally expected to be the breadwinner. Women venturing out to earn are a threat to centuries of male dominance. And film after film reinforces this stereotype through the absence of working women or in projecting one as a cause of marital strife. Even in one of our biggest recent hits, 3 Idiots, the depiction of the woman is problematic. The woman here is supposed to be a successful and brilliant professional, she rides a scooter and is ‘modern’ for all practical purposes. But it takes the hero to make her realize the truth, namely, that she is not in love with the man she is marrying. Time and again, it is the supremacy of the man that is underlined.

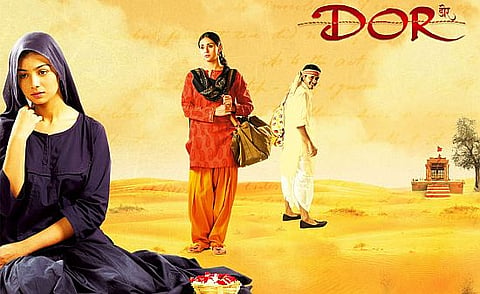

Dor

In contrast I remember a film called Dor, directed by Nagesh Kukunoor, which to my mind is a rare film because not only does it equate the woman with the marginalized man and shows the Muslim woman as more emancipated, but it also has the courage to portray a young Hindu Rajasthani widow who does not cry, who wants to dance, listen to music, and for whom life does not stop with the death of the husband. It is films like these that opt out of the patriarchal construct, even while operating from within the limitations imposed by the system, which I hope will define the contours of women in popular cinema in the future.

Few films as you can see have been able to break out of a traditional male view of a woman. And yet, the woman, whether on posters or on screen or in real life is always held responsible for inviting calamities to her doorstep. If it is not the provocatively dressed woman on the street who ‘provokes’ sexual assault, it is the item-girl on the screen who is to blame. The unrelenting gaze of society is always on women and very rarely on the behaviour, conduct and attitude of men.

Today, television is a very popular mass media run almost entirely by women and yet what do we find there? One of the most successful formulas on TV is the on-going tensions of the saas and bahu. The root cause of the ‘mother-in-law / daughter-in-law’ problem lies in the fact that both see themselves in reference to the man. Captive at home, both work towards securing his affection and largesse, with the result that both lead an imperfect life. The emptiness of these women’s lives is blamed on everything else but the husband. In tell-tale escapism, relationships are often described and determined by external things like horoscopes.

The Constitution of India guarantees equal opportunity and status to women. The principle of adult franchise seeks to ensure women’s full participation in the shaping and sharing of power. But time and again we have seen political expediency taking precedence over justice, for example, in the Shah Bano case or in the way the representation of women in Parliament was sought to be derailed by the largely male MPs cutting across party lines. And as we have seen many times over, the law is hardly a deterrent to criminals. Despite the public uproar after the December 16 murder and gang rape, the incidents of crimes against women have not come down. On the contrary, rape, acid attacks and violence against women have become endemic.

Very recently we had the embarrassment of none other than the CBI director Ranjit Sinha saying, ‘If you cannot prevent rape, enjoy it.’ The statement has rightly drawn flak but one is surprised to see the media mentioning only the reaction of feminist groups. Why hasn’t the media bothered to check with the general public, or indeed how men have reacted to the statement? Isn’t this something that should draw condemnation from people cutting across gender lines? Isn’t he as the head of CBI meant to lead by example? What message is he sending to his subordinates?

And this insensitivity is not the preserve of only men. Powerful women in influential positions have repeatedly made deleterious comments at critical junctures. A woman professional is killed while returning late from work, and we are told that women should not be adventurous enough to venture out at night. A woman is raped in the heart of a big city and again we see a powerful woman interfering with the police investigation. We constantly hear comments like ‘painted and dented’, ‘par-kati’ etc. etc. from our esteemed male parliamentarians, ridiculing modern women, thereby clearly exposing their regressive mindsets. The harmful consequences of such utterances in a society like ours cannot be overestimated.

Today, in India ‘women’s empowerment’ is a government slogan; it is a feature of every party manifesto. Yet, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, Indian women, seemingly protected by law, celebrated by the media and championed by activists, remain second-class citizens, most obviously in rural areas, but in some senses everywhere.

The picture may appear dismal but much has happened of late. At least in the capital the mood now is to listen. We will wait to see what happens next and hope the outcome will be positive for working women. Quality education alone is the way ahead. Foundations such as this are also doing yeomen service in this field and we need to build on these.

But what is of prime importance is what Anne Marie Slaughter points out: only when we give the twin pillars of human life, care-giving and bread-winning equal value will men and women attain parity at work and at home. I taught my children that whenever I left on work they wish me to get ten on ten. As more and more women venture out to work in areas traditionally dominated by men, their work whether at home or outside needs to be valued. The term ‘working mothers’ needs to be complemented with ‘working dads’. And this requires sensitizing the population, more importantly the women themselves, to the needs of women and demands made on women. The rigid lines demarcating the perceived roles of a man and a woman in society need to be merged and muted. Today, there is a huge resistance and unwillingness on the part of the man to get involved in what they perceive are domestic issues. It is a tough call and the journey ahead is not going to be easy. But it is my hope that in the not-too-distant future another speaker at this forum will have the satisfaction of saying that Indian women have made considerable progress towards realizing the motto of this Foundation: ‘the freedom to choose, the right to excel’.