Sacred Objects

There's an intriguing juxtaposition between the violence of the art-work and the violence of nationalism. Which perhaps explains why the educated middle class is essentially in agreement with the VHP that art shouldn't "cause offence".

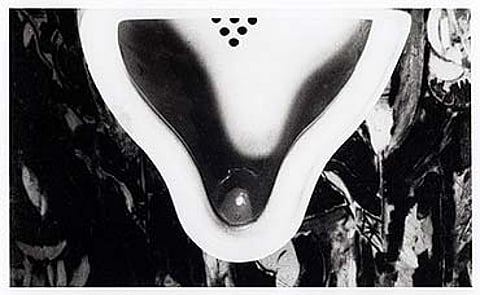

The last question probably needs competing answersdepending on the context in which it is asked. In relation to Chandramohan'sexamination entries (the one I've seen a picture of consists of a crucifixwith a penis hung above an expectant 'urinal'), the answer is an unequivocal 'Yes'.(Chandramohan, though, uses the commode rather than the lavatorialurinal in his exhibit; its renaming refers to a piece of canonical art historyI'll return to presently.) 'Yes', because this particular art-work,despite being produced by a student -- or perhaps because it was produced byone -- has educative qualities that the vigilantes have missed. Firstly, it'ssalutary to be reminded of the role of physical evacuation in our national,spiritual, imaginative life; it's at least as necessary as the faux-Victorianmessages -- such as "Cleanliness is next to Godliness" and "Commit noNuisance" -- that are scattered through our public spaces. The counterpointto those god-like ordinances is not the solitary man shitting on the railwaytracks, who's either humbled by not understanding what the signs mean, orignores them altogether; the counterpoint lies in the transformation ofexcretion into representation, 'urinal' into art-work, which sends out itsown, equally strong directive.

Secondly, like many others before him, Chandramohanis asking his viewers to reconsider rival definitions of the sacred, withan evangelizing zeal, even youthful obviousness. For, as we well know, eversince Marcel Duchamp decided in 1917 to display one, upside-down, in anexhibition space and call it Fountain (his intentions were thwarted notby a culture police, but by the organizers), the urinal has become a sacred,epiphanic object in the history of modern art, and, through over-exposure,almost as unpromising a symbol as the cross itself; it is, therefore, inconstant need of reinvention. India, with its proliferating but repressed bodilylife, is as good a site as any for the resurrection of the urinal.

One routetowards reinvention is parody, which is palpably among Chandramohan'sregisters. How long has the lone, erect, standing-up action of male urinationbeen associated with the parodic, slightly scandalous conundrum of modern art inthe popular imagination? The English phrase, "taking the piss", which meansto mock or make fun, or make a fool of somebody, and which has been in currencyfor a while, might well have originated as a shrewd working-class observation onthe Duchamp readymade.

And yet, having borne the brunt of many Tagore-songsin my life, a certain soaring quality in their author almost unfailinglytroubles my darker side. I could see his portrait hanging on a wall on the left,sage-like but for the teenager's romantic eyes, and was discomfited to feel anirresistible urge to turn it upside down. I suppose a small wave of irritationwas the cause; but it was also to escape that gaze, which had taken in such anextraordinary amount of the world, and which we no longer notice. I began tospeculate about what might justify an upside-down picture of Tagore as anart-work. Because it takes very little, a gesture, even a strategic knock, tomove an object from the space it ordinarily occupies into the one we call 'culture'. Personally, I don't think of Tagore, in the incarnation inwhich he's presented to us, as 'culture' except in a nationalistic sense:and it's nationalism that explains the tone in which the songs are sung, poemsrecited (the performance that evening, to be fair, was, in spite of beingintermittently tremulous, an intelligent exploration of the relationship betweenreading and setting), and the manner in which he and Ray have often beenverbalized in the last fortnight.

The righteous arbiters who blew up the Bamiyan Buddha (and it'snationalism, more than religion, that sanctions such outrage) were, in allowingtheir 'work' to be recorded by a camera, disseminating it to two kinds ofaudiences, in order to vindicate and satisfy one, and shock and awe the other.But, in letting the moment be reproduced, by permitting it, in effect, to passinto the realm of symbolism, they were also letting its purpose be alteredforever. Very little -- only a question of syntax and symbolism -- separatesthe violence of art-work from that of nationalism, and from the possibility ofone rearranging the other in its own language.

Both 'art' and religion have long been (in thelatter's case, with a vicious new emphasis in the last twenty years)assimilated into a form of nationalism in our country; this is why Hinduism, inthe way it's elucidated by Radhakrishnan, or represented in cinema, is oftenvacuous or assertively pious; it also explains the piety with which the Tagore-songis rendered. This isn't world-denying spiritual piety; nor is it an example ofan Arnoldian 'high' cultural piety; it's the piousness of nationalism.That's why it's no surprise to learn that a survey has discovered that theeducated middle class is essentially in agreement with the VHP that artshouldn't "cause offence".

Tags