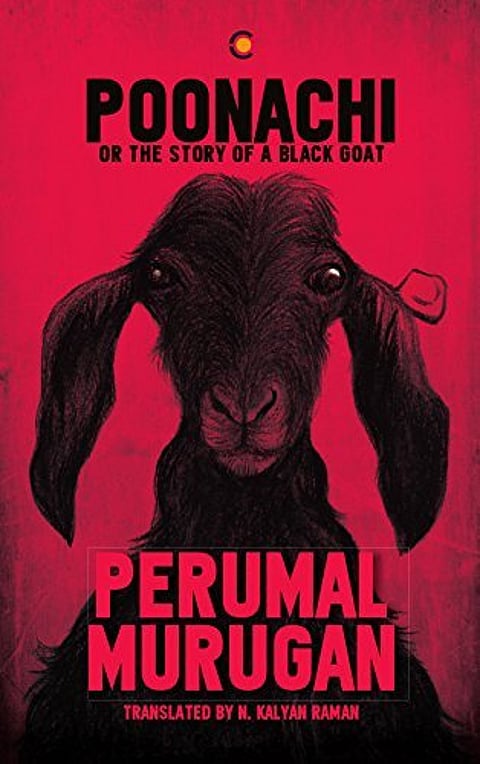

In his foreword to Poonachi or The Story of a Black Goat, Perumal Murugan seeks to give a reason why he has chosen to focus on an animal. “I am fearful of writing about humans” and “even more” if it’s about gods. If that is a subtle hint at an unexpected controversy around his previous novel, the fictionist goes on to say there are only five species of animals with which he is deeply familiar.

The Story of a Black Goat, Red Sky, Grey Village and Blue People

Only an extremely tender mind can pen a work like Poonachi. A look at Perumal Murugan’s comeback Tamil novel that takes a worldview through ashe-goat’s life along a less-green hill terrain:

“Of them, dogs and cats are meant for poetry. It is forbidden to write about cows and pigs. That leaves only goats and sheep. Goats are problem-free, harmless and, above all, energetic.”

For the not-so- unsuspecting reader, this might read like an anticipatory bail to some savage humour that is to follow as a tale. But that least turns out to be the case.

Poonachi is an extremely sensitive portrayal—of not just the central she-goat’s life, but that of her fellow beings, who include humans.

Introductorily, Perumal Murugan also says, “I can write about demons, perhaps.” Which he does prove subsequently. The novel opens to the mysterious birth of a goat. Or, rather about how an old farmer got the tiny creature from the hands of a gargantuan asura (to whose community the aged villager himself belongs) who emerges on a hilltop under a crimson sky in the dusk hour. The novel ends with the virtual disappearance of the goat, heavily pregnant and about to deliver a third time, deep into a night. A sudden act of vanish that puzzles the old man’s equally doddering wife: What lay there was not Poonachi, but a stone idol. So goes the last sentence of the novel, translated into English by N. Kalyan Raman and brought out

by Westland.

Tying just the two ends of the 179-page novel can give the impression that Poonachi revels in magic realism. Not at all. The rest of portion in the work (Rs 499) reads very real, more so if one can believe that a goat can grasp some of the verbal language of humans. It doesn’t come that hard; for Perumal Murugan is so adept in his build-up of the narrative that the reader perhaps doesn’t notice when exactly spoken Tamil becomes intelligible to Poonachi, the jet-black goat who was born last in an incredible litter of seven kids. (A pregnant goat [gestation period: five months] usually

delivers two to three babies.)

Poonachi was too tiny when the old man (whose name, like no other human’s, finds no mention in the story) is kind of gifted by an giant apparition that later finds blurred reference to gluttonous Bakasura in Hindu mythology. Listless, he brings the animal home in a drought-hit year along their countryside that lies in a rain-shadow belt of the Deccan. (Even otherwise, their region is ‘semi-arid’—an English expression that reads more journalistic [if not like one word from a geography text] and oddly seems to be a shade less literary in the novel).

Perhaps the most impressive of plots in the book (that gives names to only goats) is a journey Poonachi undertakes under her guardians: the aged couple is carrying the goat to their married daughter’s village some distance away. For Poonachi, the trip this time is a far cry from her last during which she had met Poovan, the well- mannered buck who had stolen her heart as an adolescent. Today, she is a mother—again of a supernatural litter of seven babies, but from a customary mating with a male veteran in a pen. All of Poonachi’s babies had been sold off at a high price, courtesy the uniqueness of the delivery that has earned her some local star value as well. The goat is no more a bubbly kid she was the last time; hence has a rope around her neck now. Contrary to her fears that Poovan might have been butchered if not castrated, Poonachi does meet him—and later mates with him one night that turns out to be the buck’s last. The mix of romance, sex and poignancy tends to sum up someone’s entire life.

The sight of Poovan’s headless carcass revisits Poonachi months later when one of her own kids—five does and two bucks—from the second pregnancy is sacrificed by the old couple in their bid to satisfy Mesagaran, their clan deity. For, the little one was a carbon copy of his father, Poovan.

Poonachi goes on to become pregnant a third time, by when extreme drought had made goats a rarity in the region (which had now more of sheep, which can survive in tougher circumstances). With natural resources dwindling all around, Poonachi becomes a liability for the old couple who had otherwise seen her as a fortune-giver.

The thoroughly emaciated goat seems keen to invite death than burden the earth with litter (of seven?).

Perumal Murugan’s previous (Tamil) novel was Madhorubhagan (2010), which got published in English three years later and catapulted him to national fame following right-wing protests that led the writer to announce (on social media) his “death”. That also narrates the “mystery” around the birth—of certain humans, with light thrown on a (now-obsolete) temple-centric practice followed as an option by childless couples of a Dravidian community in the erstwhile Kongunadu of the writer’s native western Tamil Nadu. In Poonachi too, very interestingly, the goat’s birth is left as a matter of intrigue that even its caretakers are clueless about despite several rounds of chitchats and debates. Poonachi having apparently turned into a stone is also a tacit example of how myths are born in a subaltern class.

Tags