A Literary Inheritance

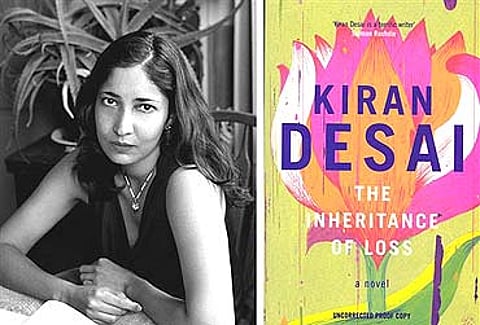

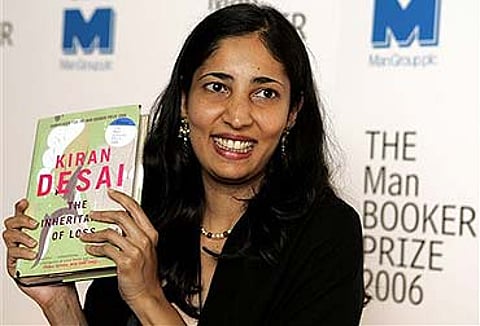

Kiran Desai becomes the youngest woman ever to win the Man Booker prize for her novel, <i >The Inheritance of Loss</i> — a prize that has eluded her thrice-nominated mother

Kiran Desai is the daughter of Anita: her arrival establishes the first dynasty of modern Indian fiction. But she is very much her own writer, the newest of all these voices, and welcome proof that India's encounter with the English language, far from proving abortive, continues to give birth to new children, endowed with lavish gifts.

Back then in 1997, these words had only been greeted with indignant raisingof eyebrows as they appeared in Rushdie's controversial essay, Damme, This is the Oriental Scene ForYou! in the New Yorker. At the best, people dismissed it as Rushdie'sattempt to be patronising or desperately trying to bolster his thesis aboutIndian writing in English. Kiran Desai's inclusion in Rushdie-edited anthology Mirrorwork,too, was criticised more for the absence of other stalwarts.

The book, when published in 1998, was received well universally, but theinterest it generated, admittedly, was largely because of her famous motherAnita Desai.

But that was then.

Kiran Desai, by emerging as the winner of the £50,000 Man Booker Prize forFiction for The Inheritance of Loss, has ensured that the acclaimedliterary prize —for which her hitherto more-famous mother has been nominatedthrice but never won—has finally found its way into the family.

The competition was fierce. Peter Carey, the Australian best-sellingnovelist, had initially been tipped to break records by winning for a thirdtime. But the jury did not include him in the shortlist, nor did it include the veteranSouth African Nadine Gordimer, who had won 32 years ago, or established Britishwriters such as David Mitchell. Instead, from a total of 112 entries, 95 bookswere submitted and 17 books were called-in for the long-list. The shortlist wasmade up of six books, the other five being:

Sarah Waters, The Night Watch

Edward St Aubyn, Mother's Milk

Kate Greenville, The Secret River

M J Hyland, Carry Me Down

Hisham Matar, In the Country of Men

Until last night, however, Kiran Desai's The Inheritance of Loss wasonly the second-favourite (the bookies' favourite was Sarah Waters' The NightWatch) though those who had read the book were confident that she had a goodshot at the prize. The Bookies seemed to have sensed the buzz, for there hadbeen a last minute rush for bets on Kiran Desai.

The judging panel for the this year's prize comprised of: Hermione Lee(Chair), biographer, academic and reviewer; Simon Armitage, poet and novelist;Candia McWilliam, award-winning novelist; critic Anthony Quinn; and actor FionaShaw. Eventually, when Chair of the judges, Hermione Lee, announced the winnerand described the book as a "magnificent novel of humane breadth andwisdom, comic tenderness and powerful political acuteness," the 1971-bornauthor became the youngest woman ever to have won the coveted prize. (BenOkri is the youngest winner ever —he was 32 in 1991 when he won the prize for TheFamished Road). Arundhati Roy, also the last Indian to have won the prize,was 36 in 1997 when she won the prize for The God Of Small Things.)

Kiran Desai's literary inheritance had been recognised, rewarded and, somemay even say, retrieved.

She was disarming in her acceptance speech: "I didn't expect to win. Idon't have a speech. My mother told me I must wear a sari, a family heirloom,but it's completely transparent!" And then, with characteristic humility,she went on to add, "I know the best book does not always win. Thecompromise wins."

But Hermione Lee, the chair of the Booker judges, dismissed any suchsuggestion "The winner was chosen, after a long, passionate andgenerous debate, from a shortlist of five other strong and original voices,"she said, ruling out the possibility that there had been any compromise. Leeelaborated the reasons for their choice: "I think her mother would beproud. It is clear to those of us who have read Anita Desai that Kiran Desai haslearned from her mother's work. Both write not just about India but about Indiancommunities in the world. The remarkable thing about Kiran Desai is thatshe is aware of her Anglo-Indian inheritance - of Naipaul and Narayan andRushdie—but she does something pioneering. She seems to jump on from thosetraditions and create something which is absolutely of its own. The book ismovingly strong in its humanity and I think that in the end is why it won."

It is an inheritance that Kiran Desai was quick to acknowledge: "I'mIndian and so I'm going to thank my parents," she said in her acceptancespeech. Being Indian is something that seems to matter a whole lot to KiranDesai, for she reverts to the same theme, at another point, "Given what the political climate has been in the States, Ifeel more and more Indian in so many ways."

Considering that the book is partly based in Kalimpong, Desai who iscurrently doing a creative writing course at Columbia University, USA, pointedout that she "went back to write the Indian bits in India, so it wasn'tentirely from a distance". And it shows, consider the following forexample:

"This state-making," Lola continued, "biggest mistake that fool Nehru made. Under his rules any group of idiots can stand up demanding a new state and get it too. How many new ones keep appearing? From fifteen we went to sixteen, sixteen to seventeen, seventeen to twenty two. . ." Lola made a line with a finger from above her ear and drew noodles in the air to demonstrate her opinion of such madness.

As Lee points out, "When you talk about a reclusive judge who has denied himself love, it makes it sound terribly gloomy but there is an extremely comic ebullience about this.The book takes on the lives of the smallest characters." But Kiran Desai'sbook is far wider and sprawling in scope as it touches on the issues ofmulticulturalism, globalization, inequality, even insurgency:

In Kalimpong, high in the northeastern Himalayas where they lived—theretired juge and his cook, Sai, and Mutt—there was report ofa new dissatisfaction in the hills, gathering insurgency, men and guns. It wasthe Indian-Nepalese this time, fed up with being treated like a minority wherethey were the majority. They wanted their own country, or at least their ownstate, in which to manage their own affairs.

But the book goes far beyond simplistic political posturing or commentary."I never set out to be political," Desai reveals. "I startedwriting about people I knew, my grandparents, my parents," she says, butadmits to attempting to write about the "less heroic side of globalisationthat's being so championed". Yet she is quick to emphasise the wit and thehumour in the book, even though it deals with "very broken people and halfstories and stories full of fears and gaps and so much hypocrisy in theworld".

Her novel, which moves between Kalimpong andManhattan, she says, deals with "the enormous anxiety of being a foreigner".She should know, for she was born in India, lived in England as a teenager for a year beforemoving to America. "I think there are many experiences that people have.They deal with deal with the journey to the West in different ways."

"It was seven, almost eight years of work, writing half stories, quarterstories, stories in eighths, of broken people, difficult lives and I picked thenovel out of it." she adds. "It was quite a difficult, emotionalexperience for me. I think I was devastated and sad by the end of the book."

Would the prize money come in handy? Of course it would. She was worried, shesays, about having to take up teaching to support herself. "My mothertold me never to be a writer because it's such a difficult profession. But ofcourse I grew up reading really hard all through my childhood."

This year marked the first time that a daughter followed her nominated-motherfor the prize and went on to win. Who knows, the mother may yet have a surprise in store forus.

Tags