An Unstamped Ticket

The Ode to Waris Shah was her defining work. Much of the rest was sheer atmosphere.

Because of her acclaim in literary circles and, of course, her good looks, a leading hosiery merchant of Lahore’s Anarkali bazaar arranged a marriage between his son Pritam Singh and her. Amrita became Amrita Pritam. They had a son. After the Partition, they came to Delhi where Pritam Singh tried his hand at business, but failed. Amrita got a job with the AIR. In Delhi, she made a decision to wipe out her past. She divorced her husband but got custody of her son. She cut off her hair and became a heavy smoker. She composed a dirge addressed to Waris Shah, author of the tragic Punjabi love saga Heer Ranjha. Those few lines she composed made her immortal, both in India and Pakistan.

Aj aakhan Waris Shah noon,

kithon kabraan vichon bol,

Te aj kitab-e-Ishq da koi agla varka phol!

Ik roi si dhee Punjab di,

Toon likh likh maare vaen

Aj lakkhan dheeyan rondiyan,

Tainu Waris Shah noon kehan

Utth dardmandan dia dardeya,

Utth tak apna Punjab

Aj bele laashaan bichhiyaan,

Te lahu di bhari Chenab

A rough translation of the last four lines would be:

Oh, comforter of the sorrowing

Rise from your grave and see your Punjab

The fields are strewn with corpses

And blood flows in the Chenab.

Amrita was a woman of modest education and wrote only in Punjabi. She could barely read any other language and was therefore unsophisticated in her writing. She was besotted with Bollywood. For her, the ultimate in success was to have some of her novels and short stories filmed. Her first novel to be translated from Punjabi into English was Pinjar (The Skeleton). I did the translation, purely out of love for her. I gave her all the royalties on one condition: to repay me with a candid account of her love life. She did over many sessions. The only passion she admitted to was for the film lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi whom she had never met. But she had corresponded with him. I was disappointed. "All this could be written on a postage stamp," I told her. So when she wrote her autobiography, she called it Raseedi Ticket (Postage Stamp). [Raseedi Ticket actually talks about Sahir visiting her in Lahore, as the above links show -- Ed, outlookindia.com]

She used to drop in frequently when I lived in my father’s house at 1 Janpath. I think she was impressed like many others by the large house and garden. She reminded me a lot of Kamala Das who also visited me in my father’s house a couple of times. The two women had a lot in common. I interviewed both of them on AIR on different occasions. Each time I asked them a simple question, they would raise their voices and disappear into the clouds. They were both incapable of giving a simple answer to a simple question.

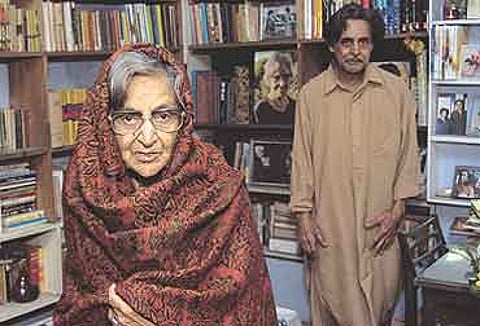

Amrita’s real love affair was with Imroze (despite his name he is not a Muslim but a clean-shaven Sikh). It was total devotion on his part and this she accepted as her due. He was a reasonably good artist and painted her eyes, which were her most attractive feature, on the door and walls of her bedroom. He designed her book jackets. He was her lover, handyman and nurse all in one. I still have his drawing of Waris Shah which they gave me.

She was a taker, not a giver. She was unwilling to acknowledge what other people had done for her. Even when Pinjar was eventually made into a film, she did not once acknowledge that it was I who had translated it into English.

Amrita started a monthly magazine called Nagmani, named after the mythical gem in the head of the serpent. It largely consisted of her own writings. She persuaded her friends to subscribe to the magazine for life. I was also one of them.

My first disappointment came when she won the Sahitya Akademi award for Punjabi literature. She was a member of the selection panel and cast the deciding vote in her own favour.

She wrote more than a dozen novels and many collections of short stories and poetry. I translated many of her poems when she won the Jnanpeeth award. Her novels and stories are contrived and no character comes alive. They are mainly about misunderstood and misused women who frequently break into tears. She couldn’t have made a living by her writing because there are few readers in Punjabi. She published her books first in Hindi and later in Punjabi. She also made a tidy fortune in awards. After winning the Jnanpeeth prize money, the Delhi government gave her a few lakhs and the Punjab government gave her another 10 or 11 lakhs. Money was never a problem for her.

Amrita got into trouble many times because of her writing. Once she was summoned by a court in Amritsar for something offensive she’d written about Sikhism. I not only wrote in her defence but agreed to appear in court with her. The case was withdrawn. Then, the Hindi writer Krishna Sobti took her to court for breach of copyright. Sobti had written her autobiography under the title Zindagi Nama (Life Story). Amrita later wrote a life of some nondescript revolutionary under the same title. I again appeared in court in her defence, saying that there could be no copyright on a title like Zindagi Nama. I collected over a dozen books with the same title from the Iranian embassy because ‘zindagi nama’ is a Persian phrase. I also submitted my two volumes of Sikh history to the court to prove that Guru Gobind Singh’s life story by one of his disciples was also called Zindagi Nama.

This earned me the ire of Krishna Sobti. She exploded in rage in the high court after the hearing, shouting: "Your Honour, don’t believe a word of what he said. He belongs to the same mafia of rich writers."

I think the most moving part of Amrita’s life were her later years. She was stricken with illness and couldn’t move. It was Imroze who looked after her with a devotion I’ve never heard of: changing her clothes, feeding her and keeping her clean.

All the praise that is now being lavished on her is mainly from people who have not read her. I feel that her only claim to immortality are those ten lines of lament to Waris Shah. Those haunting lines will remain long after the rest of her writing is forgotten.

Tags