So Mumbai schoolgirl Zara Ahmed, 15, Potter faithful and earnest muggle, woke up at the crack of dawn on June 21 to join an early morning bookstore queue for Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. It is the boy wonder’s fifth adventure, a quarter of million words long, 766-pages thick and coming three years after his last escapade. By mid-day, Zara had devoured half of the book. "I couldn’t imagine not buying it," she says.

Harry Is Hipnotic

There's something about Harry. The global phenomenon washes up on Indian shores, with that magical hold over children.

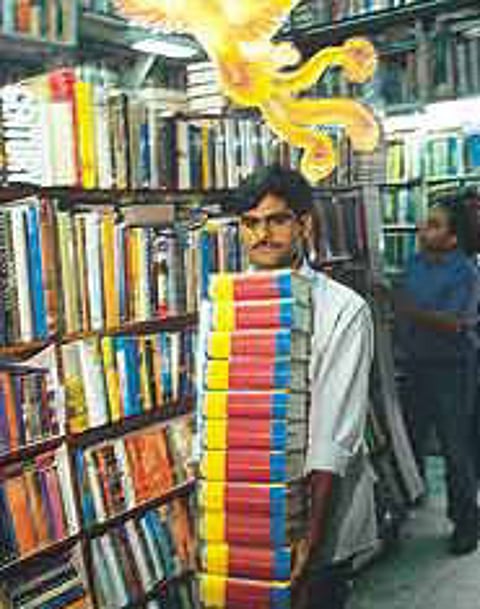

Neither could thousands of other kids and their parents, all swept up in the kind of mania India has never witnessed before. Penguin, distributor for Potter books in India, had "played safe", as a company executive confesses, by ordering 60,000 copies—almost double the amount the trade had ordered in May. By the middle of last week, traders were howling for more, and another 60,000 copies were ordered. Now, Penguin is looking at some 2,00,000 copies of the new hardback flying off the bookshelves, and half a dozen websites hawking it, in a month or so—easily the fastest selling book ever in India. (This for a children’s book that costs Rs 795.) Compare this with the 5,000-copy initial orders and sales of 30,000 copies in six months for the last Potter book, 2000’s Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, and you get the picture.

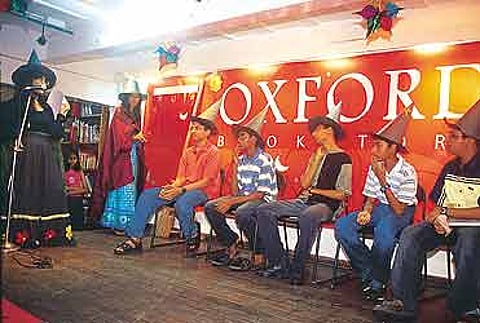

In the end, the glitzy Phoenix launch promotions at big bookstores—Potter quizzes, music gigs, free merchandise and tickets to special Potter movie screenings—seemed pretty much unnecessary. "Promotion? Do you need to promote Potter?" asks an incredulous Mirza Afsar Baig at Delhi’s Midland Book Shop, who sold nearly 1,500 copies in three days and had a queue outside at eight in the morning on June 21 to snap up copies. "I’ve been in the book trade since 1973 and never seen anything like this." At Mumbai’s Crossword, "a book was sold every minute" on the launch day, says store spokesperson Toral Sanghvi. In Bangalore, 7,000 copies were sold on the first day. "The response has been truly extraordinary," says P.M. Sukumar, vice president, sales and marketing, Penguin India.

There’s little doubt about that. But there were definite signs of the impending storm. An unprecedented publicity blitzkrieg about Phoenix had already led to a man being nabbed in Britain for trying to filch some of its pages from a printing press. In India, Bloomsbury, Potter’s publishers, inked watertight agreements with distributors, retailers and transporters not to leak copies of the book before June 21. When the copies arrived four days before the launch, they were taken to 25 heavily secured storehouses around the country. And even as the frenzy peaked with Phoenix reaching the stores, a Delhi-based copyright lawyer hired by Bloomsbury and Penguin kept tabs on a dozen "top book pirates" in Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore to stem what looks like a flourishing and creative pirate Potter industry (see box). "Phoenix will be pirated in spite of the strict watch we’re keeping. The book’s market size and appeal is awesome. It goes right down to the small towns," says the lawyer Akash Chittranshi.

What is it about Harry Potter that makes Indians—and the rest of the world—go potty? What’s so special about an orphaned child living with an execrable uncle and aunt and whose life changes after a surprise entry into a magical universe? What’s so gripping about the variegated, but folks-like-you-and-me cast of his buddies Ron Weasley and Hermione, the evil Lord Voldemort and zany props like the Hogwarts School for Witchcraft and Wizardry where Harry cuts his magic teeth, the high flying power broom sport Quidditch? What’s the big new deal about the familiar good-triumphing-over-evil story writing of 37-year-old Joanne Kathleen Rowling, who struck upon the idea of a seven-book series on a delayed train to Manchester in 1990, began writing the first book in cafes as a stone- broke single mum on dole and is now wealthier than the Queen of England? As writer Pico Iyer told Outlook, the books have struck a chord in almost every culture because Harry "seems to appeal to a universal sense, or hope, that innocence should be triumphant, that the meek can inherit the earth and that all of us, in times of war and plague, can disappear on a non-existent platform and re-emerge in a place of magic and power".

Ask Delhi schoolgirl Shagun Bhushan, 12, why she’s mad about Harry and she’ll tell you animatedly that reading Potter is like "living inside a parallel, incredible, new world". "It’s not normal, you know," she says. "It’s pure magic. And it makes me fantasise—what would happen to me if I were a witch studying at Hogwarts." Then there’s the Dickensian pathos about Harry’s character. "Oh, he’s an endearing character. You have sympathy for him because he’s abused at home, and you have admiration for him because he’s immensely brave. And he’s not vain or arrogant."

Bangalore’s eight-year-old Nihal Aarons, who’s watched the first Potter movie The Philosopher’s Stone 25 times on home video, and stocks Potter memorabilia, exults: "It’s full of suspense and surprise." Delhi’s 15-year-old Subha Prasad, a bookworm who’s into Enid Blyton, Nancy Drew and Asterix, says: "With Harry, I’m transported to a whole new world of magic, muggles, good guys, bad guys, exciting sports. It’s got just everything I can ask for." Interestingly, size doesn’t seem to matter with the young Pottermaniacs. Goblet was 636 pages, Phoenix is 766, but for young readers, it’s more the merrier. "Hey, more pages, more fun!" says Shagun. And nine-year-old Siddhartha Arjun Prasad, who read up Phoenix in eight hours flat, says: "You know what’s wrong with the book? It’s only 766 pages. It’s too short."

And Potter’s not exactly awful literature either. Rowling has created a supremely detailed world—an alternative reality—like George Lucas did in his Star Wars films. All the books are incredibly well-plotted. And they resonate with a child’s worldview perfectly, with their depiction of often-unsympathetic adults, unfair teachers, school bullies, and the first awkward stirrings of love. Then there’s bravery—which Rowling says is the greatest virtue—and moral and ethical values without being preachy. Rowling’s world is not the pleasant England of the Famous Five, but a dangerous landscape peopled with soul-sucking Dementors, and dark wizards led by the Dark Lord Voldemort who can rule the universe only if Harry dies. From perfectly mirroring a child’s distrust and fear of the adult world, the books have now moved on to reflecting Harry’s confused pubescent teenage angst; he is, after all, now 15. And at the end of it, Harry is a shy boy with not too many friends, but carrying the magical powers within himself to change the world. He is the hero that every imaginative child thinks lurks inside him or her.

Writer Namita Gokhale, who is working on a Mahabharata for children, says Rowling’s work falls into a particular tradition of English literature, typified by C.S. Lewis’s popular children’s fantasy series about the supernatural world of Narnia, and the four British schoolchildren who stumble into it. "Rowling unleashes the children’s creative imagination and has brought reading back into the mainstream," she says.

Writer Ruskin Bond tends to agree. "Potter’s easy to read, it’s not great literature, but it’s decent. Magic’s always sold well in children’s literature. But in the end, the Potter craze has been good for all: publishing, the book trade. And if it’s leading kids to read and move on to other books and foster a reading habit instead of watching television and playing video games, it’s done enough good," he says.

Clearly, Potter makes reading cool again. Radhika Menon, managing editor of Chennai-based Tulika Publishers, which publishes a dozen children’s books a year, says: "Many children who’ve never had the reading habit have picked up reading because of Potter. True, it sometimes is only Potter, but since this is good writing, there’s no harm. We only hope this will get children interested in other books." The high cover price also doesn’t seem to be much of a deterrent. Writer Gita Wolf sees a streak of irony in it: "In a society where the cultural value of a book is very low and parents grumble about prices, I find it surprising that they are willing to pay almost Rs 800 for the Potter book. It’s a phenomenon."

There are some spirited detractors as well. Like Bangalore’s Rashmi Paul or Lakhsmi Ashok or Tanvi Vasan, all 12. "The stunts like flying on broomsticks influence children to do silly things. There’s too much of magic. It’s immature," they chorus. The conservative Christian right has flayed Potter for encouraging witchcraft and the like, but as Gokhale says: "Witchcraft is not bad for kids. Satanism is, and it’s different from magic. Magic unleashes the creative imagination."

There’s another disturbing aspect. Critics feel that the huge marketing machine behind the Potter books—perhaps the biggest marketing campaign ever targeting kids—well-nigh forces impressionable children to buy them the moment they are available. Many may not be able to wade through 766 pages, but they would have bought Phoenix as hapless victims of the hype. A kind of peer pressure to be the first to acquire the books builds up—possession becomes the benchmark, not the sharing of an alternate universe. Will a child lend Phoenix to his friends? It’s quite likely that he will prefer to carry his ownership of the book as a badge of membership to the exclusive club, as a partner in a global cult of the new. The Phoenix hardback edition also can be bought only by children of relatively rich parents. Thus, the competition to read Harry’s latest exploits may also be played along income and inequity lines.

Each book in the series is darker than the previous one. The first death, of schoolboy Cedric Diggory, occurred in the fourth book; and the fifth one has more sadistic villians than ever. Add Harry’s rebellious teenage urges, and Phoenix may not be ideal reading for a nine or 10-year-old child.

But then, these are only grown-up muggle worries. While elders can go on deconstructing Potter, the kids are already asking: what next? Well, Book Six is in the works, and Rowling’s promised it would be shorter. "Seven, on the other hand, will probably be massive," she said recently. The last chapter of Seven is also written. It’s stashed away in a secret place. "Guarded by the trolls," she says. Isn’t that enough to leave the world giddy—till the boy wizard comes visiting again?

Soutik Biswas with Saumya Roy in Mumbai, S. Anand in Chennai and B.R. Srikanth in Bangalore

Tags