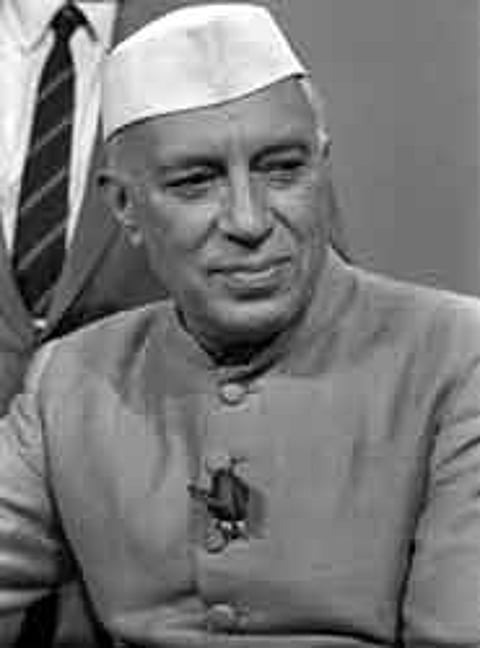

Full text of the 34th Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture at Teen Murti House, New Delhi, on November 13, 2002 by the celebrated author of The Idea Of India, who's working on a new biography of Nehru.

Nehru's Faith

What gave Nehru 'strength and hope'? What were the 'workings of the mind' upon which he grew to rely, on which he rested his faith?

By speaking of Nehru’s faith, my intentions are not purely historical. I wish to recover faith’sprimary meaning: trust or confidence, unshakeable belief or conviction – meanings that do not necessarilyimply a religious sense. It is crucial to do this, at a moment when our ideas of faith are in danger ofbecoming unnecessarily restricted. When religion is being held up as a unique source of faith, we need toremind ourselves that there are other firm foundations upon which we can build moral and ethical projects, inboth private and public life. If secularism, as we have recently been told, has multiple meanings, so too doesfaith. In our own recent history, there is perhaps no better practical instance of the effort to find anon-religious bedrock for morality than that of Nehru himself.

Unusually for a politician, Nehru was a man of deeply held moral convictions: he believed in the moral lifeas sustaining not just private life, but also as necessary for the living of any kind of political life. Yethe never placed his faith in religion. Famously, he wrote in his Autobiography of how what he called"organised religion" filled him "with horror…almost always it seemed to stand for a blind belief andreaction, dogma and bigotry, superstition and exploitation" (p 374). If he was critical of organisedreligion, he did on the other hand have empathy for the ethical and spiritual dimensions of religion. As Nehruwrote while in Ahmadnagar jail, "Some kind of ethical approach to life has a strong appeal for me" (Discoveryof India, p 12), and that ethical approach, and its sources, he discovered in the disciplined exercise ofhis mind. Reason was not merely an instrument by which to accomplish goals: through reasoning, moral ends andgoals were themselves determined, and by reasoning for oneself one took responsibility for one’s commitmentsand moral beliefs. This, I shall suggest, captures the meaning of Nehru’s faith: reason, and the processesof reasoning, are the greatest resources we have through which to create and sustain our moral imagination. Iwould like to suggest further that Nehru’s overriding importance for us at this point in our greatdemocratic experiment rests not in his obvious historical significance in India’s national story; rather, itlies in his intellectual and political understanding, in his struggles, not always successful, to try to basepublic life on a reasoned morality.

It has of late become fashionable to attack reason.In many intellectual circles, reason is portrayed as anill-effect of the Enlightenment, a banner marking the imperium of western theories and assumptions, animperium oblivious to cultural differences and diversities.The rise of postmodernism and the expanding claimsof contemporary religion are by no means directly connected; but they are also not entirely unlinked. At atime when our universities are being encouraged to produce postgraduates with degrees in astrology, it mayseem misplaced to offer a defence of reason. The political landscape today seems to have become the territoryof the non-rational: populated by new claims to selfhood – couched in terms of religion, nation, tribe,culture – all ready to use violence to assert their desires. Reason seems somehow disarmed.

In the face of this, we need to find ways to reassert a faith in reason. This will mean first andnecessarily having to see reason in a more complex light, not as a smiling rationalism or belief in humanperfectibility. "Perfection", Nehru wrote, "is beyond us for it means the end, and we are alwaysjourneying, trying to approach something that is ever receding. And in each one of us are many different humanbeings with their inconsistencies and contradictions, each pulling in a different direction" (Discovery ofIndia, p 496). It is precisely because of this – our human contrariness – that we need a capacity likereason to help find a way out of the dark, both individually and collectively. A faith in reason comes notfrom a sense of the simplicity of the human mind and its motivating passions, but from a regard for itsmysteries.

Nehru’s own understanding of reason was complex and subtle: more so than is recognised either by hisadvocates or by his critics; and it was forged in circumstances that resonate with our own: in times whenreason seemed in retreat, not at the helm – in the 1930s and 1940s, as fascism was ravaging Europe andreligious chauvinism was splintering India. Self-proclaimed Nehruvians, who have tried to subsume his thinkingunder such phrases as ‘the scientific temper’, and equally those who criticise Nehru, for what they havecalled his ‘rational monism’, both miss what is truly distinctive about Nehru’s thinking. Nehru’sfaith in reason did not lead him to an easy belief that history was on the side of reason: he was without therationalist’s faith that reason’s historical triumph was guaranteed. He saw it, as we ought to, as afragile intellectual project; and in relation to a life, it represented the attempt to hold within a mind therange of considerations on how to live.

In recent years, figures like Gandhi, Patel, Bose, and Tagore all have benefited from more nuancedinterpretations of their life and work. Nehru, on the other hand, has been treated to simplifications thatborder on caricature – passed off as a mouthpiece for a one-dimensional view of science, and of a vacuousuniversalism. This actually says more about our own times, our hopes and fears, than it does about the periodand man it claims to illuminate: almost as if it is a way of helping us deal with our disappointments andfrustrations over what our country might be.

Nehru certainly recognised the instrumental power of reason. In its two most materially powerful forms, asscientific reason (the project of trying to bend the natural world to human purposes), or as social reason(the project of trying to use human institutions – above all, the state – to remake society), reason was atool for altering the natural and human worlds, for better or ill. Yet this tactical aspect did not exhaustthe resources of reason. Reason could be used to sustain raw power, Nehru saw, but it could also be used as away of creating an ethics, sustaining a moral imagination. He saw too that reason was not a western import –there was a long and refined Indian history of reasoned argument, about ethical life and action. The act ofreasoning about history and experience was a way of discovering moral truths: through such testing andquestioning, personal identity was shaped, and moral commitments were discovered. To put it differently, moralcommitments and beliefs had to be argued for, they had to be held up to the harsh light of history andexperience. They could not be taken for granted, accepted simply because laid down in religious edicts ortexts, or sanctioned by traditions. It was precisely because morality was accessible to reason that it waspossible to bring others over to one’s beliefs – by hearing and acknowledging opposing views, and byoffering one’s interlocutors reasons to believe, by convincing them.

Nehru lived through, with varying distance, some of the darkest periods of 20th century history, perhaps ofhuman history: the first and second world wars, the Holocaust, the Atom bomb, the Partition of India. Forsomeone as sensitive as he was to history and the historical past, this inevitably shadowed his sense of whatwas prospectively humanly possible. Tagore and Gandhi both in later life ended with pessimistic and fatalisticviews about the human future. Tagore, in his late essay, ‘The Crisis in Civilisation’, gave elegant ventto his pessimism, while Gandhi’s fatalism was visible in his growing distance, in the last years of hislife, from the political sphere and his withdrawal to a realm of private moral experimentation, in order totest and strengthen his faith in god.

Nehru’s destiny was quite other: he was hurled into the ruckus of politics. Put in command of a state, hehad to act – during and after Partition – in circumstances where violence and hatred had burst knownbounds, and reason fled the scene. What kept him going was a conviction that even in the darkest times,intellectual inquiry – "the workings of the mind" as he had put it – reasoning through the gloom,could not be given up: the true failure of faith, the real moral collapse, would be to give up one’s faithin reason. If it is unusual to consider political leaders from this point of view, it is perhaps because we havebecome too accustomed to thinking of them simply as professionals pursuing a career – their declaredideology or beliefs may be of interest, but their moral character rarely intrigues us. We have come to assumethat a politician is effective to the extent that he or she is single-minded in the pursuit of power, that heshould be adept at criticising others, never himself. But anyone who chooses the political life has a moraland intellectual responsibility to be self-critical, to examine coldly their own commitments and choices. Thatmorality might have a place in the political life is perhaps an unhinged thought today, when politics hasbecome a profession rather than a vocation. Yet in the absence of such a perspective, Nehru’s career makeslittle sense: what makes him interesting as a politician, what sets him apart, is his constant probing of howto combine the moral life with the political life. He was a deeply considered person: by some way the mostcomplex whole-cloth politician that India has ever had.

If Nehru was unusual as a politician in the depth of his moral commitments, it is necessary also to see howhe was entirely ordinary, in ways that Gandhi for instance was not. Gandhi was unique: he developedextraordinary qualities of character, intensities of self-denial that seem almost freakish. Nehru was not likethat: he was, in an important sense, like any one of us – teeming with human appetites, often bewildered bylife’s choices, self-doubting, indecisive, short-tempered, needy, sometimes downcast. Unlike Gandhi, he sethimself no superhuman moral feats. But like Gandhi, he possessed a remarkable steadfastness of faith: his ownfaith. Nehru tried to use, to the utmost, that capacity all of us have: the capacity to reason.

This wider and deeper theme of our intellectual and political history has too often been subsumed withinthe story of nationalism – as the search for what could unite Indians in terms of a common identity. Yet, asthe question to which nationalism was a response has receded, as we are faced with the fundamental and routinequestions of political life lived anywhere and at any time– how can we create and sustain a moral publiclife? – we need to recover this other history, to reconstruct its shape.

What we find in Tagore, in Gandhi, in Nehru, (as well as in many others: I have chosen to focus on thesethree because they lend themselves most clearly to the argument I wish to make), in their self-criticisms aswell as in their critical debates with one another, is a search for a modern morality. They sought principlesand practices through which Indians could engage in the public political life to which they were now, throughthe presence of a state, necessarily condemned and committed. Tagore, Gandhi, Nehru: each represents animportant moment in the making of a tradition of public reason – the creation of an intellectual space whichallowed morals and ethics, and the political choices these entailed, to be debated, revised, decided upon. Atits best moments, the arguments and ideas generated quite exceeded the bounds of nationalism or nationalistthought: by which I mean that their intellectual ambitions were much greater than those who think merely interms of a narrow Indian nationalism or identity, however defined. They asked large questions, and demandedambitious answers. When thinking about moral questions, they did not ask ‘What should an Indian do?’ or:‘What should a Hindu or a Muslim do?’. Rather, they asked: what should a moral being do, what was it rightfor any human with moral capacities to do? Yet, alongside this universalist impulse, they were also compelledto keep a vivid sense of the contextual and conjunctural constraints they and their compatriots faced: thepresence of a colonial state, as also the grip of tradition, both limited the room for action. But it did notlimit the pursuit of more capacious perspectives. Interestingly, and unusually if one looks at contemporarypolitical and ethical thinking (which tends to divide between the supremely abstract and the minutelyparticular), their thinking characteristically struggled to combine universalist ambitions with a vivid senseof specific contexts in which one had practically to act.

No doubt Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru represent a broad and diverse set of positions, and they frequentlydisagreed. But together, they are the most notable examples in our history of the effort to invent a modernethics for Indians and India. Their intellectual energies in part drew upon and were directed towards a commonpredicament, a commonly felt set of challenges: how, in what form, can a moral and integrated life be livedunder modern conditions, where political power is concentrated in the state, but where beliefs are multipleand diverse across the society? What was the relationship between morality and personal identity? How couldpublic norms of morality be agreed upon? Where, to what sources should one turn in order to devise moral formsof public action? What could ensure that the institutions of modern politics – the state – would pursuemoral ends by moral means? It is the driving presence of this quest in their thinking which marks outall three as more than merely nationalist thinkers: as men who tried to find the basis for a universalistmorality and politics.

Tags