Pakistan, By Definition

From its birth as 'an Islamic home' in South Asia to its present asymmetries, former foreign minister Jaswant Singh extends themes tossed up by a new book on Pakistan

Recently, in an introductory talk on the book, the author referred, perplexingly I thought, to Aristotle, and how in The Idea of Pakistan, the writings of this great Greek philosopher had helped him understand the nature of governments in Pakistan, particularly Ayub's. Aristotle, in his unfinished Politics, does differentiate between a "right government...which aims at general good" and "a deviation...which aims at its own good". Was Cohen, perhaps, gently hinting that the Pakistani state's preoccupation with "its own good" has resulted in a near-permanent deviation of governance itself?

The cover of the book reproduces a part of the Padshahnama, depicting the siege of Kandahar (Deccan, 1630). The central figure in it is mounted on a charger and points a hand 'onwards'. Is there in this any symbolism for the idea of Pakistan? A mythological saviour of this 'land of the pure'?

For answers to these questions, we have to delve into The Idea of Pakistan. This is a most welcome and valuable addition to the subject. It's eminently readable, is full of objective insights, has been painstakingly researched and is marked by the author's characteristic scholarship. There are in this work new angles of enquiry, also observations, meriting the attention of lay readers, scholars and diplomats alike. "It has," admits Cohen, "taken me 44 years (to) write (this)—the length of time I have been studying Pakistan (and India)." Having virtually grown with the subject, Cohen's long study and deep understanding of South Asia gives him an acute insight into the region; this adds greatly to his writing.

Accepting responsibility for reviewing this book led me to revisit the bibliography on the subject. I was, yet again, made acutely conscious of a debilitating deficiency. There is not one author from India that I could identify who had written such an analysis of Pakistan. There are, of course, a number of books: on Partition, say; or memoirs; nostalgic writings; explanatory accounts of campaigns; and such other matters. But a detailed examination of the dynamics that now govern this important neighbour is just not there. Why? Why do we not have even one Indian scholar who has deeply researched and then written about today's Pakistan? I did remark upon this critical shortcoming earlier, too, when I had a more direct responsibility for our foreign policy. Is it because we assume we already know all there is to know about Pakistan? This is a serious error, demonstrating insensitivity and a gross absence of a sense of history. That is also why The Idea of Pakistan is so welcome; as a reminder, too, of what we have not done so far.

The Idea

Which then was that definitive idea of Pakistan that Jinnah stood for? He was the "second great advocate of a distinctive Muslim identity" who, having "joined the Indian National Congress in 1905", became an "ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity". Ironically, it was Jinnah who later was most "responsible for the merger of the 'idea' of Pakistan with the 'state' of Pakistan". Was this idea then just a bargaining counter? And, in reality, not meant as a genuine launching pad of Muslim separateness? Ayesha Jalal, in The Sole Spokesman, controversially asserts this, while Anita Inder Singh in The Origins of Partition offers a totally contrary view. It does little good now to visit that painful episode other than to enhance our understanding of the 'idea'. But either way this articulating of the 'idea', but not any territorial definition of it, was a necessary tactical device because Jinnah knew that he did not have the "political resource" needed to go any further. That is why a mean was adopted, of the 'two-nation' theory. In Lahore, on March 23, 1940, Jinnah set forth his logic.

"The Hindus and the Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literatures...to two different civilisations...." and so on. (An echo here of Al-Biruni?)

What was the import of such assertions about nationhood? If "Indian Muslims were a 'nation' entitled to equal treatment with the Hindu 'nation'," and this over time was accepted and became non-negotiable, then 'shared sovereignty', as enunciated by Jinnah and the Muslim League, was not just the next logical step, it was the "best way of tackling the dilemma", of an absence of any congruity between "Muslim identity and territory". That's also why a sharp "demand for a separate, sovereign state with no relationship to a 'Hindustan'" remained undefined and open "until the late summer of 1946". (Quote: Jalal)

But there were several others: both other 'ideas' of Pakistan and other viewpoints. Above all was that "third towering figure...Allama Iqbal", who worked as effectively as Jinnah or Sir Sayyed for Pakistan. Iqbal too "began as an advocate of Hindu-Muslim unity" and was also, ironically, the author of Sare jahan se achchha, but he changed, advocating later that Muslims of India "needed a separate state...a South Asian counterpart of the great empires of Persia, Arabia", because "political power was essential to the higher ends of establishing God's Law". (Quote: Jalal)

Then, there was the Aga Khan, who in the mid-'30s advocated a "United States of South Asia", but no separation. From this was born 'safeguards', that "if minority communities were to 'become citizens of self-governing provinces'", then they must have "safeguards from the 'majority' community before settling on Swaraj". Jinnah grasped the import of this before others could; for him it was the long-sought-after "political opening". His campaign was launched, resulting, in December 1939, in the announcement of the Day of Deliverance, which was more a deliverance from 'Congress raj' than the Hindus. Complications remained; this "search for a Muslim whole" kept boomeranging, particularly "on Punjabi proponents". Besides, the Unionists were always there. Sikander Hayat Khan championed them, of course, in tandem with Chaudhury Sir Chotu Ram. Speaking in Gurdaspur in May 1939, Sikander boldly proclaimed that "he was first a Punjabi and then a Muslim". (Quote: Jalal)

It was in 1933, that "Choudhary Rahmat Ali, a Punjabi Muslim student at Cambridge, coined the name 'Pakistan', an acronym for Punjab, Afghanistan (including the North West Frontier Province), Kashmir, Sind and Baluchistan. Literally, the land of the pure". Initially this was scoffed at, but it began to gain currency in "informal arenas". Nevertheless, opposition to "a Muslim state of 'Pakistan' dominated by the Punjab" always remained. On a separation, for example, of Sind from Bombay presidency, "the Sindhi Muslim leader Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah. ..(in July 1934) told a meeting of the Sind Azad Conference that it would be a political blunder for Sindhi Muslims to group with Punjabi Muslims".[I have relied on Ayesha Jalal's scholarly and meticulously researched Self and Sovereignty for several details, in this analysis of the evolution of the idea of Pakistan.]

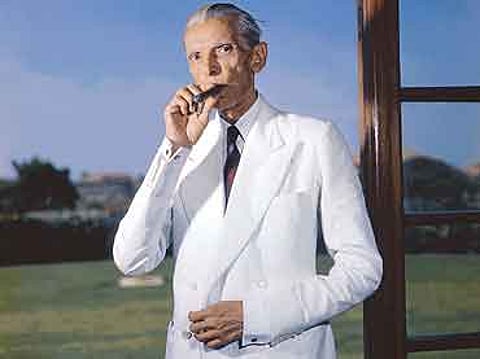

What about Muslims in the rest of India? Rather grandiosely "Choudhary Rahmat Ali proposed setting up half a dozen Muslim states in India and consolidating them into a Pakistan Commonwealth of Nations". Also, did all 'Indian Muslims' subscribe to this demand? It is difficult to estimate what "percentage supported" the scheme of Pakistan in those years. The Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind certainly did not, "always kicking up a storm about Jinnah's lack of religious disposition". The two Maulanas, "Hussain Ahmed Madani and Hafiz-ur-Rahman of Delhi", breathed "hellfire on Jinnah for 'having no beard, for not fasting during Ramzan and for frequenting clubs and cinemas instead of saying his prayers'". That is when Jinnah astutely took to wearing the "sherwani and a karakul cap, which (later acquired) his name", thus making "a show of his Muslim cultural identity". But he did not ever commit the All-India League to "basing 'Pakistan' on Quranic principles", nor accept "demands to oust the Ahmadis from the Muslim community". (Quote: Jalal)

On August 11, 1947, the Quaid-i-Azam, after appointment as the president of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, made a speech from which what follows are just excerpts:

".... A division had to take place. Both in Hindustan and Pakistan, there are sections who may not agree...but in my judgement there was no other solution.... I am sure future history will record its verdict in favour.... Now what shall we do? If we want to make...Pakistan happy and prosperous, we should...forgetting the past, burying the hatchet...work together in a spirit that everyone...no matter (of) what community...(or) colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations."

Noble sentiments, but alas they had no effect. It was too late. Even as Jinnah spoke, caravans of humanity trudged hopelessly out of this new state of Pakistan, also into it, to this new home; finally, a separate land. But cruelly, the Boundary Award came much later; at that stage no one even knew how their land stood divided! Many million laments hauntingly filled the air in India and Pakistan. Individual pain got voice (still continues to)—by poets, playwrights and authors. The loss was not just individual, or in the Punjab and Bengal alone. Established geographical and economic entities, ancient cultural unity, having evolved over millennia into a distinct commonality, got fragmented; the historical synthesis of an ancient land and its civilisation was fractured. Was this the long-sought-for Idea of Pakistan?

Cohen glances at this question—but just that and no more. He says, "A united India would be a great power, whereas a divided one would be weak," and "the British (could) use an independent Pakistan to control India"; this idea later "resurfaced with the US replacing Britain". The author leaves the thought there, without much elaboration, appropriately so perhaps. Besides, post-World War II a depleted Britain could just not have continued as masters in India. They had to leave, but surely they need not have left such destruction behind?

Recent research by Raja Narendra Singhji of Sarila, a distinguished former diplomat, which he uses in his shortly-to-be-published book, The Untold Story of Partition—Shadows of the Great Game, has an interesting angle.

Field Marshal Lord Wavell, then Viceroy, who was in London in August 1945 for a policy review with the new Labour government, advised: "There is no possibility of a compromise between the Muslim League and Congress. ... We've to come down on the side of one or the other." On August 31, 1945, after a farewell call on the by now out of office Churchill, Wavell wrote: "He (Churchill) warned me that the anchor (he himself) was gone and (that) I was on a lee shore with rash pilots.... His final remark, as I closed the door of the lift, was: 'Keep a bit of India'". Wavell did just that. By early February 1946, a blueprint of a future Pakistan was sent to Pethick-Lawrence. It contained some details that almost two years later the Radcliffe Commission finally and formally announced. That is why we are led to ask which 'idea' of Pakistan did Jinnah actually stand for? Also, whose 'idea' finally took shape?

Cohen does refer to an absence of a strategic evaluation of Partition but again, in passing. No one, not Nehru, nor Patel, nor Jinnah nor any other proponent of Partition ever assessed in depth its strategic costs; or its linkage with the global consequences of World War II; and—at another level—even with Jinnah's health. There is a sense of deep irony when we revisit the fateful coincidence of some of those epochal dates of early 1947. Truman proclaims the Charter on March 12, 1947; Churchill at Fulton announces the descent of the 'iron curtain'; the Asian Relations Conference opens on March 23, 1947, in which Pandit Nehru eloquently speaks of 'Asian solidarity', 'Third World unity', and so on. But irony of ironies—all this when Mounbatten had already reached Delhi, and when in reality a blueprint of the partition of India was already under finalisation. (Divide India? Yes; but simultaneously announce 'Asian solidarity'?) The implications of a divided South Asia on the strategic calculus of an emerging, indeed imminent bipolar globe did not feature in India or Pakistan's calculations. Very damaging consequences inevitably followed, and soon, for both countries. Almost blindly, India and Pakistan got locked into much larger global conflicts; and their bilateral relations, most damagingly, also got intermeshed with emerging superpower rivalry.

Idea to Identity

How then did the 'idea' flower? How did Pakistan fare? Always accompanied by high drama, by the dark and looming shadows of history, also myth, and by an absence of sharp, cold logic, the 'idea' got usurped early. That is why Pakistan's friends so often became its masters, and that is also why the state of Pakistan continues to remain fragile, so unsure, so tense. But there were other factors, too.

Because there was not just one 'idea', this movement for Pakistan bequeathed to the emerging state of Pakistan a number of identities. "First," says Cohen, "Pakistan was clearly 'Indian', in that the strongest supporters of the idea of Pakistan identified themselves as culturally Indian, although in opposition to 'Hindu Indians'. This 'Indian dimension of Pakistan's identity'...systematically overlooked by contemporary Pakistani politicians and scholars" creates a cruel dilemma—for it can neither be rejected nor acknowledged by Pakistan. How to reject the reality of one geography, or pervert totally a common historical past? Even the emergence of Pakistan—from where-what-why?—then gets twisted out of context and shape. And yet when reminded of this oneness, citizens of Pakistan bristle and go instantly, angrily rejectionist. Cohen lists some other 'ideas', those that worked or did not. "A modern extension of the great Islamic empires of South Asia"— this did not happen. "Pakistan...a legatee of British India, in the 200-year-old tradition of the Raj" became instead, and most unfortunately, a "rented state". Did "cultural links with Central Asia" make "Pakistan a boundary land between the masses of India and the vastness of Central Asia"? No, because the geographical, historical reality and cultural logic is totally different."Pakistan as part of the Islamic ummah"? Yes and no, the question mark is appropriate.

Evolution to State

Cohen suggests that "refugees (initially) gained control of the government, bureaucracy and business in the West Wing.... Traditional Punjabi and Pathan leadership—(was) frozen out". "A triad consisting of the army, the bureaucracy, and the feudal landlords came to dominate the politics and social life of the Indus basin." By 1965 and 1971—post-Bangladesh—Pakistan became a "fortress—an armed redoubt guarded by the Pakistan army, safe from predatory India". There were many other factors, too, that contributed to this siege mentality. To list them is uncalled-for but two certainly merit mention: Jinnah's early death, and a consequential loss of authority in government; this rapidly declining into impatience with democratic norms, demands and restraints. To this was also added a sense that India was "somewhat contemptuous" of Pakistan's ability to survive: "Let us see for how long they last," remarked Pandit Nehru. (Quoted by B.K. Nehru). Such sentiments cemented existing resentments and suspicions.

The Mohajirs, soon disillusioned, are tragically left neither at home in Pakistan nor in India. "Jammu and Kashmir" became both a "cause and a consequence of Indo-Pak hostility". Pakistan, like many "Islamic populations", found it difficult "to retain a modern state". Akbar S. Ahmed notes, "Muslims feel the West (has) a hand in this outcome, (it) has stripped them of dignity and honour, and confusingly restoration of honour gets equated with violence". Is Pakistan complete now as an 'idea'? Not really, because despite Bangladesh what rankles some in Pakistan is an uneven migration of Indian Muslims, the large numbers left 'behind'...(which) renders Pakistan incomplete.

Reality

From the original Idea of Pakistan to today's reality has been a long, tortuous journey. Cohen comments on this under various heads: "Army's Pakistan"; "Political" and "Islamic Pakistan", then provincial pulls in "Regionalism and Separatism". Pakistan's economy and its prospects, which only occasionally invite comment in India, are dealt with in detail. Pakistan's "alarming demographic and social indicators", the much-abused education system and the "uncertain economic circumstances" are eye-openers. Cohen asserts that these "sectors...are intertwined: when positive (they) reinforce...a virtuous cycle; when...negative, the cycle becomes vicious, and a state may spiral downward or stagnate". The most alarming is Cohen's projection of "Pakistan's demographic future", which he asserts will impact powerfully on that country's identity. Pakistan's population, growing almost at 2.9 per cent annually, is the "highest (rate) in the world". This is "matched by massive urbanisation". At this rate, Cohen estimates that Pakistan's "population is expected to reach 219 million by 2015" and "Karachi to have 20 million residents" by then. Pakistan will admittedly have a young profile but "with a population that can't find opportunity within Pakistan...and is unable to leave the country, masses of young men (will thus be) ripe for political exploitation". The "Establishment" has "never paid much attention to the population problem" because "for some Islamists, a nation of Islamic warriors backed by an Islamic bomb represents an unstoppable force"; a large population is thus "a strategic asset"!

Current Percepts

It is not the purpose of this piece to present a detailed historical narration of Pakistan's journey along the path of guiding its own destiny. The percepts that currently guide its policy formulations are central, however. This 'operational code' of Pakistan's Establishment, says Cohen, comprises:

As "India is the chief threat to Pakistan...(it) had to be deterred (militarily), strategically.... Punjab (is the) heartland. Military alliances (are) necessary"; also therefore, "borrowed" power."Kashmir was an important issue even if the Pakistani masses did not think so.

Tags