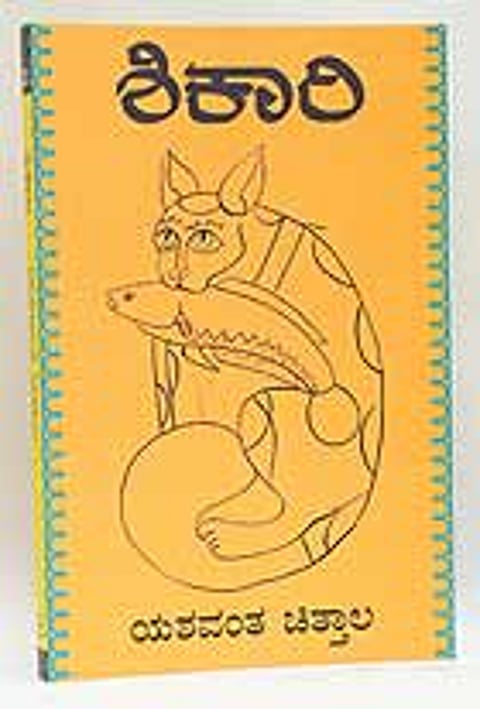

| Shikari By Yashwant Chittal |

The Ballad Of Babel

The Booker winner finds a novel that pierces through Mumbai’s masquerade, capturing its miasmic heart

Shikari explicitly acknowledges its debt to Kafka in its first few sentences; then it goes to places that Kafka had never dreamt of. Even as Nagnath is coming to terms with Bandookwala’s treachery, he finds himself the victim of another act of betrayal. Nagnath, an orphan who educated himself with a scholarship from Bombay’s Saraswat Brahmin community, discovers that Srinivas, a childhood friend, is spreading word that his mother was a low-caste woman, and that he’s been masquerading all these years as a Brahmin. Srinivas has even gone all the way to Goa, the ancestral home of the Saraswats, to collect information about Nagnath’s true lineage.

Instead of fighting back, Nagnath goes into a shell. We learn that Nagnath (much like Chittal himself) has been writing Kannada short stories when he is not at his day job. Now in his crisis, he responds as a writer would: by jotting down a series of notes, possibly raw material for a novel, in which he records his growing anxiety. When a genial old man, a stranger, whom he sees at Shivaji Park, inexplicably strikes fear into him, he runs into his room and writes: “Am I running because I’m frightened? Or is it that the fear is generated in me because of the physical act of running? Must remember to read William James again.”

Nagnath’s erudition only serves to highlight his increasing coarseness. Asked about his mother’s origins, he responds: “Get your hand out of my genealogy, you son of a bitch!” If the swearing occurs equally in Kannada and Hindi—behenchods alternate with bolimagas—the novel is also full of English abbreviations and phrases—DMD, MD, R&D, Manager, Special Assignment, Personal & Confidential—that give us a flavour of the Bombay corporate world of the 1970s. Entire sentences sometimes appear in English, pitch-perfect in their sensitivity to the novel’s mix of farce and existential angst, as when a Parsi executive tells Nagnath (in English): “Sorry for being so coarse. But I am sure you will agree with me when I say that the prime mover of the organisation—the motive force behind the facade of its evolving structure and all that four letter jargon is the ambition of the individual to climb its tall ladder.” The multi-lingual dexterity of the novel is one of its great charms. Warned that he might be cast out of the S.B. (Saraswat Brahmin) community of Bombay, Nagnath welcomes his expulsion from “your S.B. (S.O.B.) society”.

Shikari has magnificent descriptions of the teeming and multicultural life of inner city Bombay: from his flat in a Khetwadi chawl, Nagnath stares out at bhaiyyas carrying milk in aluminum cans, boys selling newspapers, Udupi restaurants, the printing press of the Communist Party that stands at the entrance to a galli, and an old man sitting in front of a portrait of Dattatreya and singing loud bhajans. (Why such a successful executive continues to live in a congested chawl is one of the mysteries surrounding Nagnath, as are the strange burn marks on his chest, and the question of why he is avoiding the comfort of his mistress during such a crisis.) Bombay is a source of food and drink for the bachelor Nagnath, but it is also a beacon to suicide. We discover that his father killed himself, and that his mother’s death, as is so much of his early life, is shrouded in obscurity. Watching the waves crash into Chowpatty beach, Nagnath wonders if he should plunge himself into the water, much like his father had done.

Beer is one way to stop thinking about suicide. Nagnath drinks, prodigiously: in the Sher-e-Punjab restaurant, in his home, in corporate guesthouses, and even in Irani cafes without a permit that serve him beer behind a curtain. When that does not help, he starts using barbiturates. Unexpectedly, he finds another kind of relief: suddenly, all the women he meets, whether it’s the Christian secretary from his company or the Irani air-hostess on the flight to Hyderabad, start propositioning him. Is this really happening, or has he started hallucinating under the influence of beer and barbiturates (as he himself suspects)?

By shifting between Nagnath’s first-person notes and a third-person narration, the novel undercuts the objectivity of its protagonist’s perceptions. Yet, it never relinquishes its power to pass judgment on the Bombay of the late 1970s, a society obsessed with status, class, and profoundly hypocritical in matters of sex. In a powerful scene, Nagnath discovers why his friend Srinivas has been “investigating” his origins. Srinivas confesses that he has heard a rumour that Nagnath plans to write a novel about his life—a novel that will be serialised in the Illustrated Weekly of India and will tell people that Srinivas, though a successful businessman and a respected member of the Saraswat community, began life in extreme poverty. This is an India before Dhirubhai Ambani, when self-made men did not brag about their origins—in this India there is no greater shame than the shame of having once been poor. Going down on his knees, Srinivas begs Nagnath not to expose his past, because he is planning to run for office in the upcoming Municipal Elections. Now Nagnath understands why Srinivas and Phiroz Bandookwala have been gunning for him: in their eyes, he is the shikari. He turns and runs for his life.

Concrete jungle Behind its giddy skyline, Mumbai’s is a harsh land. (Photograph by Abhijit Bhatlekar)

Shikari is rich with references to existential philosophers like Camus and Erich Fromm, but it’s in a parallel series of images drawn from Hindu mythology that Chittal maps his protagonist’s transformation into a man who rejects his former existence in the corporate world, even when he is given a chance to clear his name and go back to his job. On his way to the dreaded inquest, Nagnath catches his own image in a mirror in the Taj hotel. He is half-expecting that his inner crisis has transmuted him into a Shiva or Buddha: “Outwardly there was no change: no horn had sprung on his head, no new eye had opened on his forehead.” An even more poignant image comes at book’s end. Running out of a brothel, Nagnath arrives at an epiphany that is both surprising and logical, unexpected and triumphant: he understands what he has been suppressing since his childhood, and what he must do with the rest of his life. “His Vanvas has just ended,” we’re told. “The Ajnatavas still lies ahead.” It is the most moving finale to a novel that I’ve read in years.

Yashwant Chittal is one of the Kannada poets, short story writers and novelists who flourished in Bombay after Independence. Some of these writers are dead; some, like the short-story writer Jayant Kaikini, have gone back to Karnataka. Chittal—now in his eighties—is still here. Thousands of Mumbaikars gather every evening at the Bandra Bandstand, but even the most literary among them are unaware that they are right outside the home of a novelist who has captured their city as well as Suketu Mehta or Salman Rushdie. Shikari is my favourite Bombay book; with its blend of learning and raffishness, black comedy and existential anxiety, its obsessive inquiry into ethnicity and the urban experience, it reminds me of Saul Bellow’s great novels. Given the right translator, and even moderate backing from a publishing house, it will establish itself as a classic of modern Indian fiction.

***

Blurbs Prima In Indus

Outlook’s top reads on Bombay

- Salman Rushdie Midnight's Children

- Suketu Mehta Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found

- Vikram Chandra Love and Longing in Bombay

- Gillian Tindall City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay

- Katherine Boo Behind the Beautiful Forevers

- Anita Desai Baumgartner’s Bombay: A Note

- Rohinton Mistry Family Matters

- Jeet Thayil Narcopolis

- Sonia Faleiro Beautiful Thing: Inside The Secret World Of Bombay’s Dance Bars

Tags