“All my life I have been tormented by ghosts. Since Delhi has more ghosts than any other city in the world, life in Delhi can be one long nightmare. I have never seen a ghost nor do I believe they exist. Nevertheless for me they are real.”

The Ghosts Of Khushwant Singh's Delhi

We are answerable for having let our religious identities drive us to killing each other. Khushwant Singh has shown us some of our handiwork in <i >Delhi</i>.

Khushwant Singh, Delhi: A novel (p 164)

An out-and-out bestseller in India when it was first published, Delhi has rarely been acknowledged as an ambitious and powerful literary work. Despite being one of perhaps only two Indian English novels, along with Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines, to grapple with the 1984 riots directly, Khushwant Singh’s magnum opus has received little serious critical attention. Even Amitav Ghosh, while explicitly bemoaning the absence of literary responses to the 1984 riots, omitted to mention Khushwant Singh's novel. This regrettable omission occurs in Ghosh’s essay “The Ghosts of Mrs Gandhi” where the writer describes his personal encounter with the happenings in Delhi in November 1984. He also explains that the primary literary concern that underlay his own response to the 1984 riots, The Shadow Lines, comes from his reading of the essay “Literature and War” by the Bosnian writer Dzevad Karahasan who says: “The decision to perceive literally everything as an aesthetic phenomenon—completely sidestepping questions about goodness and truth—is an artistic decision.” The reference here is to the depiction of violence and Karahasan is particularly critical of “people who observe and experience the most horrendous suffering of their neighbors as a mere aesthetic excitement.” The concerns engendered by his reading of this essay pushed Ghosh to move descriptions of violence offstage and focus on the lives of people affected by it instead. But Khushwant Singh had already shown, in the novel Delhi that was published around the same time as The Shadow Lines, and some years before Ghosh’s essay, that it is possible to depict violence in a way that forces us to confront questions of goodness and truth.

The question that Ghosh asked in 1995 is still pertinent as we approach the 30th anniversary of the anti-Sikh violence. Why has it been so difficult for Indian English novelists to face up to the 1984 riots? Ghosh's own The Shadow Lines, started a few months after the riots veers into the past and away from Delhi to Kolkata, Dhaka and London. But, to the best of this writer’s knowledge, there is no work that speaks as directly and fearlessly to the horror that was visited on Delhi that year as Khushwant Singh’s novel. And this despite the fact that those few fateful days of November 1984 appear in just 15 out of almost 400 pages of the book; 15 pages that, coming, as they do, at the very end of the book, at the very end of a long and poignant telling of Delhi’s history, transform the moment of violence into pure pathos and prevent it from ever being reduced to mere spectacle.

In the course of the book Singh also fornicates with a “big-bosomed” American teenager visiting Delhi and, separately, an Army wife left behind in Delhi while her husband is on a non-family posting, but his primary attachment is to a foul-mouthed and extremely charming hijda called Bhagmati. Singh, who appears to make an irregular living by the pen, finds Bhagmati passed out by the side of the road and rescues her one day while crossing the Ridge from office to home; the in-betweenness of the place where he finds her is not belaboured, but cannot be missed. Despite his initial hesitation and chowkidar Budh Singh's disapproval (“take a woman, take a boy... but a hijda?”) Bhagmati and Singh become lovers, meeting when it suits “her” fancy. This relationship lasts through multiple decades, its intensity and the regularity of their meetings flagging as old age begins to have its effect on Singh’s sex drive, doses of that best of aphrodisiacs, vitamin B, notwithstanding. By the time we get to the 1980s it has been years since she has visited Singh. But when riots hit Delhi in 1984 she does return, concerned for the wellbeing of her old lover, repaying in kind his many kindnesses and the open-hearted friendship he has shown her through the years.

Singh, the narrator, is both the consummate insider as well as an outsider of sorts. He is a conformist in his recognition of the hierarchies and social structures of the city, and in his zestful exploitation of the possibilities these structure provide him. But he is a non-conformist in his freedom from the fetters of family life and in the fact that his most enduring sexual relationship is with a hijda. It is a relationship, moreover, that he has little control over since Bhagmati visits him when she pleases and there is nothing he can do about it, living as he does in an era where telephony is a luxury, prevented as he is by shame from going to fetch her from the hijdas’ quarters in Lal Kuan. He is licentious but caring. He emphasizes the raunchy nature of his existence but is unafraid to reveal his poetic side. He is a man but he is not macho. The particular cocktail of contradictions Singh embodies recalls another denizen of Delhi who lived a century prior to him. The one who said about himself:

yeh masa'ail-e tasavvuf yeh teraa bayaan Ghalib

tujhe ham valii samajhte jo nah baadah-khvaar hotaa

Alternated with a series of episodes of Singh’s life—episodes that all seem to be set in post-Independence India—are weighty first person narrations by an ensemble cast that spans Delhi’s recorded history from the early years of the Delhi Sultanate to the fateful days of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. Two emperors, two invaders and one great poet (Mir, not Ghalib) speak to us in their own voice, as do some “subalterns”: a court scribe, an untouchable, an Indian soldier fighting for the British and, finally, a Hindu refugee from what is now Pakistan.

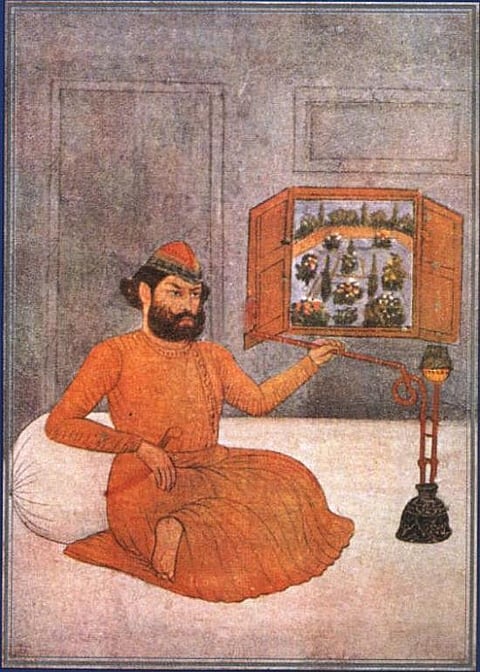

Engraving of Mir Taqi Mir by Richard Earlom, 1786

Apart from these there is, of course, also the voice of the son of one of the contractors who built New Delhi. This particular person, “the builder,” is a man of means, unlike some of the humbler figures from the past, but he does not possess fame that will span centuries like the grander figures do. His voice is the joker in the pack. It is not the axis on which the book turns, but it is a clue to the raison d’etre of the book itself. It is as if, we can speculate, the generation that builds the new city must also tell the story of the cities that have preceded it, and, in telling this story, must equip those who take residence in the new city, who take on the mantle of being Dilliwallahs, with the wisdom that will help make the travails of the future easier to understand.

There is also a sense that his meditation on the processes that brought a set of enterprising and industrious Sikhs, of which “the builder” is one, to the forefront of the construction of New Delhi kindled in the author a desire to investigate the intersection of Sikh history with the history of Delhi. The first point in this intersection is Jaita Rangreta, an untouchable from the Rikabganj area living through the transition between Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Rangreta who is a scavenger is unhappy at having to pay the Guru's agent on the occasion of the accession of the new Guru, but consoles himself by thinking that at least this makes him something, “a Sikh of Guru Nanak,” which is better than being an untouchable. The name Jaita Rangreta, and his heroic act of rescuing the head of the executed Guru Teg Bahadur after his execution by Aurangzeb, lines this character up with Bhai Jivan Singh, a Sikh general who served with distinction under Guru Gobind Singh. But Bhai Jivan Singh was born and raised in Patna, not in Delhi, and his father, rather than being a humble and foul-mouthed man as the father of the Jaita in the book is depicted to be, was, in fact, Bhai Sadanand, a companion of Guru Teg Bahadur’s. This transposition of a Bhai Jivan Singh into Jaita Rangreta, a dom working in the executioner’s yard clearing dead bodies, is a novelist-historian’s manoeuvre that calls for interpretive powers and an understanding of Sikh history deeper than this writer possesses, but one simple thing becomes clear: the radically egalitarian nature of Sikhism endows the act of handling and carrying a severed head with great spiritual merit, an act that would be impossible for a caste Hindu to ever conceive attempting.

In Mir Taqi Mir’s account of the political upheavals of the latter part of the 18th century—clearly drawn from the poet’s eminently readable memoir Zikr-e-Mir—the Sikhs reappear in passing as a rampaging group of savages who have vanquished the Afghans and have their bloodshot eyes set on Delhi. And then again they return to the gates of Delhi under the command of Major Hodson, helping him to finally crush the 1857 uprising by executing Bahadur Shah Zafar’s sons. This adversarial relationship with Delhi turns proprietorial as Sikh contractors bribe their way into the good books of the British officers overseeing the construction of the new capital following the coronation of King George V as the Emperor of India in 1911. The first-person historical interludes carry the strand of Sikh history only so far. But it is this strand that allows the two major lines of the novel to merge when the narrator Singh and Bhagmati are witness to the latest bloody point of meeting of Sikh history and the history of Delhi: the 1984 riots.

Sikhs gather in front of a painting depicting 1984 riots during a protest. AP Photo/Altaf Qadri

The people who live in this city are deceitful, they have always been, even the ones history has subsequently forgiven. Amir Khusro, great Sufi and poet, is, in the Kayastha scribe Musaddi Lal’s telling a two-faced man who had served many masters. “If anyone knew when to turn his back to the setting sun and worship the new one rising, it was Khusrau,” (p 73) says Musaddi Lal, referring to the poet’s agility in changing patrons whenever power shifted, a trait that is as much in evidence in our own times as it was in Balban's era. A century or so later Timur, having vanquished Mahmud Tughlak and been feted as he entered the city, realizes that the citizens of Delhi are willing to pay lip service but are not willing to pay actual tribute. “It does not take long for the men of Hindustan to switch their minds from fawning flattery to deadly hate,” (p 100) he concludes, a sentiment echoed centuries later by another invader, Nadir Shah, who, bemused that debauched Mughal nobles would attempt to taunt him for being materialistic, when his own intention in marching to Delhi was to protect Islam, concludes that “the people of Delhi are both ungrateful and cowardly.” (p 182) In both these cases the “hand of rapine” is extended to the general populace as retribution for their mendacity, and tens of thousands are killed.

In a humanistic, or perhaps Sufi-like, inversion of received wisdom, the writer turns antagonists into protagonists. And so when Nadir Shah unsheathes his sword and proclaims the forfeiture of every citizen’s life, we find ourselves understanding why he would do such a thing. Thus too we find ourselves nodding along with Aurangzeb when he explains to the reader how his piety and love for God moved him to kill his depraved and unbelieving brothers and imprison his father on the way to the throne of Delhi. The avenging sword of Islam attempts to curb the moral turpitude that, the book seems to argue, is endemic to this city and deeply entrenched in it, but no matter how much blood is spilled the chicanery continues in one form or the other. Aurangzeb is the last Mughal to attempt to create a moral order in the territory that is his to command, and although at the beginning of his reign he is filled with a sense of the rightness of his purpose—“If God had not approved of my enterprise,” he writes to his imprisoned father, “how could I have gained victories that are only the gift of God?” (p 158)—by the end of his life his certitude is destroyed. “The instant that passed in power has left only sorrow behind it,” (p 160) he writes to his son in his last days.

'Capture & Death of the Shahzadaghs', 1857. Coloured lithograph from 'The Campaign in India 1857-58', by William Simpson, E Walker and others, after G F Atkinson, published by Day and Son, 1857-1858. National Army Museum Copyright

The British come, in their time, and take over the reins from the last Mughal, bringing with them a new standard of right and wrong. Major Hodson, who has arrested Bahadur Shah Zafar and himself shot three of the emperor’s sons in full public view just outside the gates of Delhi is offended when his orderly asks him if it is true that the heads of the three princes were severed and shown to their father. “The sahibs are civilized people,” he says, “they are not like the natives of Hindustan. They do not cut off people’s heads and present them on trays to their relatives.” (p 310) But the British are not the first whose notions of civilization are undermined by Delhi’s crippling corruption. Eventually, as we learn from the builder of New Delhi, they too succumb to bribery and favouritism. The wheel of history turns full circle when the Sikh contractor, who has just bought an automobile from the money he has made in building the new capital and driven his family to Qutub Minar for a picnic, lies on a dhurrie gazing up at the magnificent tower.

“I wondered how much the contractors had made out of the job. It was obvious they had stolen a lot of stone and marble from older buildings. Did they pass it off as new? Did they have to bribe architects and overseers to have their bills passed?” (p 336)

The moral thrust of the book, and a modicum of hopelessness regarding the human condition, comes to the surface in this somewhat wry and otherwise harmless passage. More than the deviousness of the Hindu immigrant who is brainwashed by the RSS into attacking a Muslim businessman in Connaught Place from behind his back and killing him, more than the sly ways of the assassin who touches Mahatma Gandhi’s feet before shooting him dead, more than the treachery of the bodyguards who fire a hail of bullets into the body of the unarmed woman they swore to protect, it is the Sikh contractor’s banal reverie that triggers a bottomless despair. But this is not a general lamentation on the treachery that is the nature of man. The argument is more specific. Cities are, by their very nature, sites where power, political or economic, is concentrated, the author seems to say. Delhi, the seat of the empires of Hindustan from the times of the Lodhis and Balban down through the Mughals and the British into the era of republican democracy, has, like an old and rusty tanker truck, been a longtime storehouse of a highly corrosive political power. It is not just rulers, or would-be rulers, whose moral sense is eaten away by this acid. The poison is in the water. Everyone has drunk it.

The narrative of mutual mistrust begins with only two major communities in the early years of the Delhi Sultanate, a time we see through the eyes of the Kayastha Musaddi Lal. A Hindu by birth, he studies at a madrassa because it is the only route to enter his forefathers’ profession of court scribing. Pushed by his friends at the madrassa to convert to Islam to further his job prospects on the one hand, and, on the other hand, suffering sexual frustration because his wife’s family does not want to send their daughter to the house of a man they suspect has converted to Islam, Musaddi Lal finds his own small life caught, like the small lives of many others in times to come, in the crossfire between two competing religious complexes. He dresses like a Muslim while his wife weeps at the sight of mosques embellished with mutilated figures of Hindu gods and goddesses. But Musaddi Lal’s story has a happy ending. He finds solace in Nizamuddin, the dervish of Ghiaspur, who becomes his “umbrella against the burning sun of Muslim bigotry and downpour of Hindu contempt.” (p 62) By the time of Aurangzeb, however, the dervish has retired to his tomb. With the man who feared no sultan dead, the reins of spiritual power on Earth fall slack and it is left to the wielders of temporal power to stake their claims as protectors of faith. The “living saint” Aurangzeb is not much like the dead one. He has temples destroyed and imposes taxes on non-Muslims. He becomes, to use an idiom current in our times, a divisive figure, especially when Shivaji enters the scene and challenges his authority. The author presents the voices of caste Hindus cursing Aurangzeb and pinning their hopes on Shivaji, and Muslims berating Shivaji for deceitfully murdering the general Afzal Khan having pretended to be a friend. We recognize in this argument faultlines that cannot easily be erased. Both sides have committed indefensible crimes. Each speaker identifies with one side against the other—both imbued into the person of a single individual, Shivaji or Aurangzeb—on the basis of religion. There is a fear of what the other group is capable of. There is the easy transmutation of fear into hatred. We know this schema well.

Some pages before the Aurangzeb-Shivaji episode there is a scene set in the post-Independence era where Singh the narrator is meeting a Sikh journalist and a Hindu politician, both old friends of his, at a coffee house. There is curfew in the city because of the anniversary of the martyrdom of Guru Teg Bahadur. Trouble is anticipated and the Hindu politician, out of fear and irritation, exclaims “You can never trust the Sikhs.” The Sikh journalist gives back as good as he gets, accusing the Hindus of provoking the Sikhs against the Muslims. There is a feeling of vertigo here as history churns into the present since a few pages later we will be told by Jaita Rangreta that in the days leading to the same Guru Teg Bahadur’s execution at the hands of Aurangzeb, the Hindus of Delhi did not celebrate Dussehra and Diwali, closing ranks with the Sikhs, or, perhaps, just opportunistically adding to the pressure generated by the arrest of the Guru to register their protest against the Emperor’s general harshness towards non-Muslims. Juxtaposing the discussion in the coffee house in the twentieth century against the happenings in Delhi in the time of the Guru's execution, we realize that the relationship between Hindus and Sikhs, the relationship that would come to a bloody pass in 1984, is the author’s primary concern. The Muslims, who have largely been purged from Delhi after Partition, are not a factor any more. But their memory lingers and is used, like memory always is, to score political points. In her seminal essay on the 1984 riots “Crisis and Representation: Rumor and the circulation of hate,” Veena Das quotes a whitepaper entitled They Massacre Sikhs, published by the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee in 1978, in which the author Kapur Singh harks back to the publication of the scurrilous pamphlet Rangila Rasul in 1927, dwelling on how “the entire Muslim world of India writhed in anguish at this gross insult to and attack on the Muslim community but were laughed at and chided by the Hindu Press of Lahore.” Reading this along with the brief but portentous coffee house passage from Delhi we realize that in the lead up to 1984 the Muslims were only a counter to be passed back and forth between the Hindus and the Sikhs, whose trust in each other could have said to have broken down to the extent that we begin to doubt if such a trust ever existed.

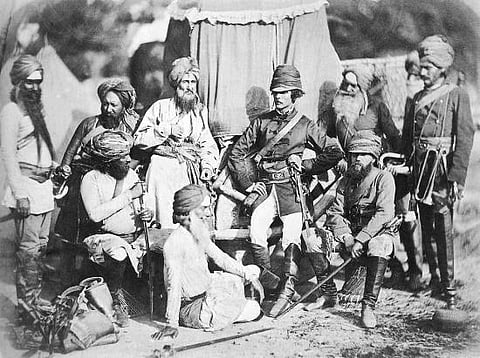

British & Native Officers of Hodson's Horse, 1858 by Felix Beato

It is to the novelist’s credit that the British are cast as interlopers in this narrative of fraternal mistrust, opportunistic interlopers who are happy use this mistrust to their advantage. For example, they recruit Sikhs to fight against the rebels in Delhi in 1857 by citing the fact that the Mughal Emperor who is the leader of these rebels is a descendant of the same “Auranga” who killed Guru Teg Bahadur. Nihal Singh, the voice of the Sikh recruits in this novel, is impressed by the bravery of the British officers, but—and here the empire writes back in a minor key—realizes that at some fundamental level his masters are savages when the beautiful sight of peacock in full glory dancing on a rooftop is interrupted by a bullet from a gora gun. Having valorized the British for their prowess in battle and undermined them for their susceptibility to bribery and their inability to appreciate another culture's beauty, the novelist ultimately removes them from the equation, negating the self-serving and, ultimately, self-deceptive line of argumentation that seeks to blame the British for all the ills of the subcontinent. Near the end of the book the builder of New Delhi, now old and close to death in an independent India, holds his own against a “nationalist” who tries to shame him for praising the British. When asked if he has forgotten Jallianwala Bagh, he says he hasn't and continues: “Nor have I forgotten what Indians have done to each other. I can show [you] some of their handiwork in Delhi.” (p 344)

This, then, is the crux of the book, the argument that has been developed over a few hundred pages and several hundred years: We are answerable, each one of us, for having let our religious identities drive us to killing each other, for never having trusted one another. The author has shown us some of our handiwork in Delhi.

“Muslim corpses strewn across the muddy meadow, a Serb soldier grimly standing guard. ‘‘So,’ we asked the soldier, this young kid,’ Rieff recalls, ‘‘What happened here?’ At which point the soldier took a drag on his cigarette and began, ‘Well, in 1385...’’”

Perhaps not as sharply focused as in Bosnia, the force of particular narratives of history is felt in Delhi as well. The memory of his sister’s abduction in what is now Pakistan fresh in his mind, the young Hindu refugee willingly swallows the narrative of Hindu victimhood that the Sangh’s teachers tell him and becomes part of a plot to assassinate Gandhi. The urge to avenge Aurangzeb’s execution of Guru Teg Bahadur spurs on Nihal Singh to join the British army in 1857 and kill those who fight for Aurangzeb’s descendants. The granthi from Singh’s local gurdwara likens the Indian army’s entering the Golden Temple to a desecration committed by the Mughal nobleman Massa Ranghar in 1740, vowing revenge similar to Ranghar’s beheading by two Sikh daredevils who entered the his presence pretending to be revenue officials, a vow that is later completed by Indira Gandhi's bodyguards in an episode that carries echoes from that earlier assassination. History when told like this makes us begin to despair.

But the novelist who embraces the cause of humanity, who believes, as Karahasan believes, that “[the] values and choices [that are the foundation of human ethical existence] are most immediately articulated and determined by literature” is not likely to give up, even in the face of such persuasive evidence that history is easily subverted to evil ends. This novelist believes that the poison can become the antidote and chooses to tell history again in the belief that it can heal, and that it can show us all a way for the future. In Delhi at one point we find the narrator deciding at 3:30AM to get rid of his phobia of ghosts by visiting the tombs of Lodhi Gardens. But those tombs are not simply beautiful pieces of masonry in a picturesque landscaped setting for this very early morning walker. His mind wanders over the names and deeds of those who are buried in the tombs, implicitly inviting us to do the same, thereby de-aestheticizing the monuments, subtly suggesting a deeper role for those buildings in the lives of the people who often walk by them without realizing the lessons that have been petrified in them.

Trilokpuri, Delhi 1984. Only one male Sikh was left alive. Archival photo.

The novelist also answers Karahasan’s call for a literature that provides “a partial identification with a fictional world; an identification that would make possible a fuller comprehension and understanding of one’s own self, through a temporary sojourn with an Other.” He does so by, for example, taking us into Aurangzeb’s head, teasing out his motivations, presenting the misguided purity of his intentions, showing us Dara—latterly lionized as a tragic poster boy of a composite culture—as a weak-minded coward whose encouraging of unbelievers was dangerous for Islam. As we settle into the logic of Aurangzeb’s voice, we begin to empathize with the same man whose name arouses untold hatred in Nihal Singh a hundred years and a hundred pages later. Apart from Aurangzeb, we also hear from the invaders Timur and Nadir Shah, two other major villains of Delhi’s history, and from a young man who is involved in the plot against Mahatma Gandhi. Despite being trained to regard Mahatma Gandhi as the great unifier, we begin to feel for the young RSS recruit when he says “How could you put sense into the skull of a man who keeps saying, ‘I am right, everyone else is wrong’?” (p372) We have all met people who infuriate, and eventually alienate everyone around them, by insisting on being correct at all cost. Threading a small personal irritation normally reserved for domestic arguments into the buildup towards one of the defining tragedies of modern India, Gandhi’s assassination, is a novelist’s gesture that allows us to approach that moment through the antagonist’s subjectivity, to feel the humanity of those misguided young men who have been the other for the Indian state since the early days of its inception.

While facing up to the fact that antipathy between a self and an other is an ineluctable part of the historical record, the author also flirts with the possibilities that lie beyond the binary. So, there is Musaddi Lal, neither Hindu nor Muslim, who seeks refuge in Nizamuddin, and, of course, there is the backbone of the entire book, Bhagmati the hijra, who is neither man nor woman, or, looked at another way, is freed from being either by being a bit of both. The narrator’s love for the hijra, fleshy and physical as it is in its depiction, is perhaps a metaphor for the human being’s love of that which lies beyond the self and the other, for our collective yearning for an end to the hatred, the suspicion and the divisions that sunder us, for that concept that could be called divinity and is, in some sense, the ultimate goal of humanity.

In the foreword to the paperback edition of Delhi, Khushwant Singh writes that it took him 25 years to write this book. The book was published in 1990, which means that he had been writing it since 1965. This qualification—perhaps a riposte to Dhiren Bhagat who, in his “obituary” for Khushwant Singh written in 1983, called Train to Pakistan a “Partition quickie”—is worth reflecting on because it means that the author had already been working on this book for almost two decades when the 1984 riots happened. We can only speculate at what he had or had not already written by that time. We can only wonder if we are being invited to compare the dervish of Ghiaspur who throws the deed to the empire of Hindustan into a pitcher of urine to the “demented monk” Bhindranwale who endangers the lives of innocent pilgrims by installing his armed bunch in the Golden Temple. We can only hypothesize that the rioters who ironically raise the cry of “Bole so nihal, Sat sri akal” after murdering the mentally retarded Budh Singh are responding to the same cry raised by Nihal Singh and his Sikh comrades when they pass Gurdwara Sisganj, their myopic motive of revenge for Guru Teg Bahadur’s execution having helped establish the ultimately destructive rule of the British in India. Put simply, the 1984 riots, when they come at the end of the book, appear so seamlessly that it is hard to believe that they had not already happened when the book was conceived.

Touched by the fact that the hardcover edition of Delhi sold out even before it reached bookstores, Khushwant Singh wrote of the book in the foreword to the paperback edition that “I put in it all I had in me as writer: love, lust, sex, hate, vendetta and violence—and above all, tears.” He goes on to reveal his real motive in writing the book: “My only aim,” he writes, “was to get [my readers] to know Delhi and love it as much as I do." It remains to be seen if anyone will, in the future, love Delhi as much as the author of this stupendous work did, or bring all of Singh's erudition, zest for life and remarkable spiritual depth to bear in expressing that love. But, while we wait for the next such person to appear, let us pause for a moment to wonder how a city as degraded, dirty, deceitful and downright hostile as Delhi can inspire such love, and what the nature of this love might be.

Amitabha Bagchi is a novelist living in Delhi.

All page numbers are from the paperback edition ISBN 9780140126198, first published by Penguin Books in 1990.

Tags