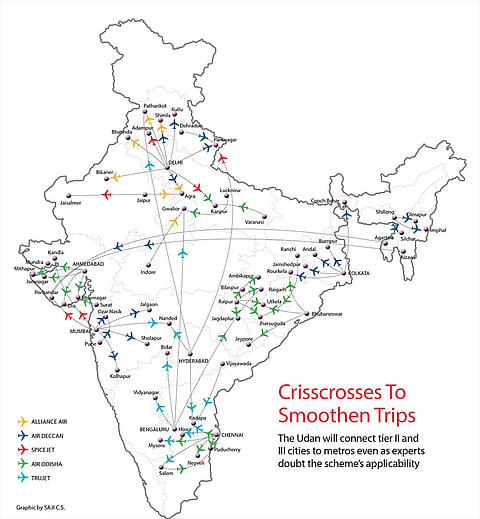

The grid is set to become a lot busier. And countrywide at that. In the next few months, India’s aviation map will look a lot vibrant, thanks to a government endeavour. The new Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS), or Udan, will bring smaller cities like Bikaner, Pantnagar, Kanpur, Agra and Pathankot on the Indian aviation network—not without doubts cast on its applicability and efficacy.

Clouds Across Matrices

It’s aimed high. But will stronger regional air connectivity actually work?

The RCS, which the government announced recently, seeks to bring in connectivity between tier II and III cities and also link them to major cities, including metros. A lot of questions are, however, being asked about the way the scheme has been designed and about the viability of the airlines in the scheme.

Under Udan (Ude desh ka aam nagrik), the government has approved 27 proposals from five airlines to connect 43 airports on 128 routes countrywide. The five airlines selected are Alliance Air, SpiceJet, Turbo Megha Airways Pvt Ltd, which will run the TruJet Brand, Air Deccan and Air Odisha Aviation.

The RCS is expected to give a huge push to investments, tourism and job creation in the states and hitherto untouched areas. The government has high hopes from the scheme and expects it to be a game-changer. “The Udan network will cover the whole country, giving a major economic boost to hinterland areas,” says civil aviation minister Ashok Gajapathy Raju.

The RCS was the cornerstone of the National Civil Aviation Policy announced in June last year. The government said the funding of the RCS cannot be done through the exchequer and hence money will have to be shored up from within the sector. There’s a small levy of around Rs 60 per passenger on the main routes that will fund the central government’s contribution towards viability gap funding (VGF) for the regional carriers.

So, to promote the scheme, the government has announced several incentives for the participant airlines. This includes VGF to ensure viability, concessions in fuel in terms of excise duties and exemption of airport and parking charges. Oil accounts for 45-55 per cent of an airline’s costs. The VAT and excise duty on ATF and service tax on tickets have been drastically reduced. Airport charges have been waived off. Police and fire services will be provided free of cost and utilities like power, water and drainage will be provided at discounted rates. These are benefits the aviation sector never enjoyed earlier.

The scheme, if successful, may correct a mismatch in flying between major cities in India. At present, the top six metros account for 66 per cent per cent of the total passenger traffic in India. Delhi and Mumbai alone account for around 40 per cent. There are 58 million passengers using Delhi airport and many of those are non-Delhi flyers who use Delhi as the connecting point. The RCS is designed to change that.

India has 414 airfields and airstrips lying largely unused. These were considered for the RCS. The selection was through online competitive bidding. After airlines bid for a particular route and put up the security deposit, it is the responsibility of the Airports Authority of India (AAI) to get that regional airport ready for operations. The problem is 31 of the allotted airports have seen zero traffic and will be connected to the national air grid for the first time. These airports would have to be readied by the AAI for commercial use.

To make the scheme attractive for flyers, the government has designated 50 per cent of the seats as RCS seats and capped the fare at Rs 2,500 for 500 km or roughly an hour’s flight. The government will provide VGF for each RCS seat. The balance seats can be sold at market price. Operators on RCS routes will get a three-year monopoly on those routes. All this makes the Udan an interesting proposition.

Experts point to issues that may come between the success and viability of regional airlines. First at the larger airports, slots are just not available. Mumbai, for instance, has no slots currently available, while Delhi has very few—even those at odd hours that may not suit regional airlines. And it would be tough to replace a large plane to accommodate a smaller RCS aircraft.

Also, quite importantly, small and slow-moving aircraft flying between larger ones slow down the entire traffic, affecting efficiency and timeliness of the entire chain of airlines, given that the runway occupancy time for smaller aircraft is more than larger aircraft. The Association of Private Airport Operators says the timing of flights has to suit small towns and depends on slots they get at large airports. “But it is difficult to get slots at large airports like Delhi and Bangalore in peak hours,” notes its secretary-general Satyan Nayar.

G.R. Gopinath, Ajay Singh

Also, unlike in many other countries, India does not have second airports in major cities to take traffic from regional carriers. Air India’s former executive director Jitender Bhargava points out that no separate terminals exist for regional or low-cost carriers. “How will high airport charges be accounted for in metro airports within the Rs-2,500 cap? Who will reimburse a Delhi airport for landing charges?” he asks. “On the one hand, you have a congestion charge for large airports. On the other, you give freebies in the name of regional connectivity.”

Large metros need a second airport for general aviation and RCS flights. But that will take four to five years to happen given the changes of land acquisition and myriad permissions. The Navi Mumbai airport in Mumbai is still at least three years away, while a proposed one at Jewar near Delhi is not even in planning stage. So to begin with, RCS flights may have to be allocated non-peak hours.

Importantly, the cost of running smaller aircraft is higher than that of larger aircraft. Also, returns per passenger are low as compared to larger aircraft. Higher maintenance cost is another issue. Says Amber Dubey, partner and India head (aerospace and defence) at KPMG: “In smaller aircraft, the fixed cost of crew salary, leases and maintenance are spread over a smaller number of seats. Hence the cost per seat goes up as the aircraft size reduces.” Under RCS incentives, he notes, the 48- and 78-seaters appear to be highly profitable. “Smaller aircraft of 9 and 19 seats capacity may have to use innovative strategies to ensure viability.” How will they, for instance, pay the pilots anything less than what is being paid for large aircraft?

Some experts question the government’s very approach in the scheme to bring in regional connectivity. Says aviation consultant Mark Martin, CEO, Martin Consulting: “The whole Udan initiative is cock-eyed and fundamentally flawed, as you are creating connectivity through a subsidy scheme. The very fact that you are bringing in subsidy to show viability is a disaster—for, viability of regional airlines depends upon external factors like fuel costs, currency fluctuations and imports.” Also, he says, viability of small aircraft is based on the number of hours it flies. The more a small aircraft flies the more money it makes. So they have to make the aircraft available to fly throughout the day and that may not be possible especially to larger airports where time slots are not available.

Viability will also come if there is enough traffic from a particular station. And that might not happen as the fare may still be higher than train or road options for a majority of travellers. Only business circuits may have good traffic. The Delhi-Agra route, for instance, has excellent road connectivity and might not have takers for flights. The other issue is that since many of the airports have not seen any flights, they are merely airstrips without any airport infrastructure that needs to be built. It will take a long time if all the stations were to be developed.

Martin says he gives the scheme six months to a year, after which it will become unviable. The government, of course, has high hopes—and feels that traffic will come from the small cities and justify its plan to make it a success. But the real success of the scheme will come in when the loose ends are tied. And that will take time. International experts, though, are hopeful that India will become one of the largest aviation markets in the world in the next few years, courtesy increased connectivity. And that is towards what the government is working. The next six months will be decisive. Some of the airlines in RCS have the experience and resources to bring in results. Perhaps they will lead the way to make it a success.

Tags