This story was published as part of Outlook's 1 November, 2024 magazine issue titled 'Bittersweet Symphony'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

Tata And The Art Of Global Acquisition

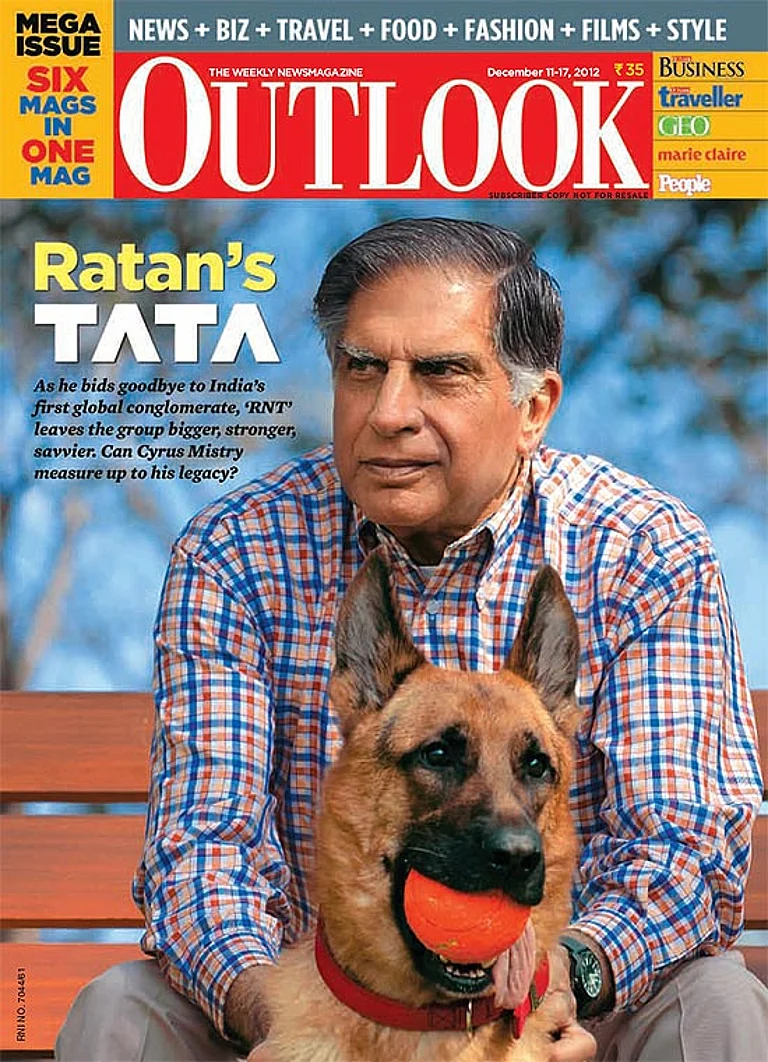

Ratan Tata's formula for managing international acquisitions found success with Tetley and JLR; but his track record suffered a bit when it came to Tata's largest purchase

On September 30, the last of the blast furnaces at the Port Talbot steel mill was shut down. With that, a Wales town that has lived and breathed steel production since 1902 stepped into the unknown. About 2,800 jobs will be lost in this southern coastal town as the plant replaces the blast furnaces with arc reactors. For Britain, it also spells the end of an era going back to the Industrial Revolution as it loses its ability to produce primary steel—the incoming electric arc reactors will only be able to reprocess scrap metal.

At the heart of all these regional and national changes in the UK is a familiar name—Tata Steel—and a story of global expansion driven by one man.

Go Forth and Acquire

In the 1980s and 1990s, suspicions about foreign ownership were still very much in the air in India. It had been only a few years since George Fernandes, Industries Minister in the Janata Party government, had thrown Coca-Cola and IBM out of the country. For companies wanting to enter the Indian market, one available route was joint ventures (JVs). With regulatory restrictions in India against 100 per cent foreign ownership, Tata became a favoured local partner for many companies, including for IBM to re-enter the market and for Pepsi to try its luck where Coke had burnt its fingers. These JVs not only brought in foreign brands to India but also gave Tata exposure to new products and technologies, providing them an edge over domestic competition.

However, post-1991, as India liberalised its regulatory framework, many of these foreign partners exited the JVs to venture off on their own. Now the question facing Tata was how to ensure growth for its companies with potential. The idea that evolved in the strategy sessions of the late 1990s was—go out and acquire. And it had the right man at the helm to achieve this. Someone who was keen on breaking the passive image of the Tatas and putting the group on the cutting edge of global technological advancement.

Ratan Tata Steps Out

The year was 1983. It had only been a couple of years since JRD Tata had elevated another Tata as chairman of Tata Industries, a position that could be a direct route to the leadership of the group. But amid the satraps that headed the various industries in the group jostling for the top spot, the 46-year-old Ratan Tata had much to prove. While by the side of his mother, who was under treatment in New York, Tata chalked out what came to be known as the Tata ‘Strategic Plan’ for expansion.

“Keen to change the passive image of the Tata Group, Ratan wanted to propel it to the cutting edge of technology. His argument was that the Tatas have all along been pioneers, taking up frontier industries,” says Gita Piramal in her book Business Maharajas.

The strategic plan spoke about personal computers, AI, supercomputing, and the ‘convergence of computers and communications into information technology and biotechnology’. “It was quite a forward-looking paper,” says Ashutosh Tyagi, former vice-president of Tata Industries who has been on the board of several Tata companies. “He could foresee some of these things becoming big, maybe not immediately, but in the coming years. In fact, when I wrote the strategy for Tata Industries in 2007-08, it still had many of those same terms that he had used 24 years back. At that time, I felt that some of these things would never happen. But things have obviously changed in the past five-six years for some of these technologies,” adds Tyagi.

The strategy paper, though supported by J.R.D., found little traction among the other senior leaders in the group, according to Piramal. Tata had to wait over a decade before he could act on his ambitions for the Tata Group.

Appointed Tata Sons chairman in 1991, Ratan Tata’s strategy in the late 90s focused on acquiring companies that could help Tata enter higher-margin markets, especially internationally. One of the companies with which this happened first was Tetley, a household name in the UK that is credited with introducing the concept of tea bags to the market. Tetley Tea, then the world’s second-largest producer of tea bags, was three times the size of Tata Tea when the latter bought it at $432 million in 2000—the largest takeover of a foreign company by an Indian one till then. There was a certain synergy in this purchase since Tata owned plantations across India that produced tea while Tetley purchased teas that suited its customers. This purchase also gave Tata Tea not only access to a higher-margin branded market but also the space for certain experiments around integrating with an international acquisition, says Tyagi.

On Hostile Takeovers

Ratan Tata was opposed to hostile takeovers as a matter of principle. “If they oppose, we walk,” he had said in an interview in 2007, setting the support of the board as a necessary condition for the Tatas to come in. In the case of Tetley in 2000, the existing management was left largely undisturbed. The view was that other than providing support, there should be no large-scale intervention. This has been described by some Tata veterans as the “feather-touch approach” to acquisitions—the opposite of the kind of large-scale changes that are often seen when acquisitions happen. “The approach was that as Tatas, we will not go around doing a bull-in-the-china-shop kind of thing. Post merger, we would let that entity which we have acquired by itself. We’ll provide support, which is financial, which is somewhat strategic, directional. But we will not transfer people en masse from India to that setup,” says Tyagi.

Tata followed this approach again in 2008 when it took over another marquee British brand, Jaguar Land Rover, from Ford in a $2.3-billion all-cash deal. That year, JLR was running at a loss of $400 million. In fact, Ford chairman Bill Ford told Tata, “You are doing us a big favour by buying JLR”.

Behind that line, there is an oft-repeated story of humiliation and sweet retribution. In 1998, when Tata Motors was looking to divest its passenger car division after the dismal performance of the Indica, Ford evinced interest in the same. The story goes that at a meeting with Ford executives in Detroit, Ratan Tata and team were told that they had no clue on what they were doing, and that Ford was doing them a favour by buying the unit. Cut to 2008, and the Ford chairman’s statement was a turning of the tables.

Returning to the JLR deal, Ratan Tata realised that while the automotive company may have been in the doldrums, it had a rich set of designs in the pipeline. He left the JLR management in place and gave them what turned out to be the best form of intervention—his time and money.

Ratan Tata, who had hands-on experience in the automotive industry, started spending time at JLR’s main production facility at Solihull, England, and Tata poured billions of pounds into research at JLR without imposing any form of cultural changes on the firm. In Ratan Tata’s own words: “We aim to support their growth while holding true to our principles of allowing the management and employees to bring their experience and expertise to bear on the growth of the business.”

Tata’s approach and well-known social commitments made it the preferred buyer for JLR’s workers unions as well. A senior leader of the automotive workers’ arm of Unite, Britain’s largest union, said in an interview at the time that the “Tatas are into making cars, not just making money”.

The investment appeared shaky at first due to the heavy debt burden it landed Tata in amid the Great Recession of 2008, which saw demand for luxury vehicles fall globally. However, JLR turned out to be Ratan Tata’s best bet, and the rare case of a company from a developing nation turning around a corporation it acquired in a developed economy. With the success of its models like the Range Rover Evoque and the Jaguar F-Type, JLR went on a profit streak that peaked at £2.6 billion in 2015.

Tata’s Approach Falters

The track record of the Tatas with minimalist intervention in foreign acquisitions suffers a bit, however, when it comes to its largest purchase—Corus. In 2007, Tata Steel outbid Brazil’s CSN to take over the Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus for a staggering $12.2 billion—the biggest acquisition abroad by an Indian company till date. The company, which owned several steel plants across the Netherlands and the UK, including the Port Talbot mill, was later rebranded to Tata Steel Europe before being split up into Tata Steel Netherlands and Tata Steel UK.

Corus, formed by the merger of British Steel and the Netherland’s Koninklijke Hoogovens in 1999, was a potpourri of a company. “Corus was a very different entity from the other two (Tetley and JLR) because it had been artificially put together by some financial investors with the Dutch portion and the English portion. With a new owner, the people who had been in the Corus system were expecting large-scale changes. Those changes and directions maybe did not come with the urgency that the situation needed. Tatas took time to develop a more hands-on approach, which left the current management confused, directionless for longer than the situation demanded,” says Tyagi. Tata was still in hands-off mode, though the disjointed nature of Corus meant it merited a more direct approach.

With steel consumption collapsing during the global recession and the arrival of cheap Chinese steel, Tata Steel started bleeding money at the rate of over a million pounds a day in its UK operations. It is in this context that the then Tata Sons chairman Cyrus Mistry tried to sell off Tata Steel’s UK operations in 2016, and the ensuing drama saw Ratan Tata forcing out his chosen successor. Tata Steel held on to its UK operations, estimated to have cost the company over £5 billion in losses over the years.

“It is hard to think of many owners that would tolerate the same level of financial pain and keep going,” writes Nils Pratley, financial editor of The Guardian. “At some level, the decision seems to have flowed from the group’s roots as a company that talks about the importance of community,” he adds.

Tata’s persistence on investments seem to make no financial sense unless viewed in the context of the long-term involvement that is in the group’s ‘roots’. Tata veteran Tyagi notes: “The only reason why some of these acquisitions and the prices paid for them make sense is that they’re not looking to acquire so that they can create value and exit. Everything is strategic. Nothing is financial. ‘If we are in, we are in forever’ is the thinking.”

(This appeared in the print as 'When The Jaguar Leaps')