The Juice Corner

The Left gone, will reforms take a front seat? Well, not exactly.

- Focus on consolidation in sectors that directly impact people, like power, healthcare, water resources, roads, aviation

- Pension reforms and giving more voting rights in private banks

- New R&R bill and amended Land Acquisition Act for compensation and relocation of project-affected persons

- Bill to promote micro-finance institutions, pending in Parliament

- Big focus on unorganised sector, proposed social security legislation

***

- Top agenda is not reforms, but to bring down double-digit inflation, maintain growth momentum

- Disinvestment of PSUs will remain on backburner as it is still an emotive issue with most political parties

- Given the focus on the impact on the small stores, further opening up of retail sector ruled out for now

- Status quo expected on big-ticket labour law, insurance sector reforms

- Given the time factor, government will have to prioritise what legislation to push through

***

At last count, the government has 72 bills waiting for approval in both houses of Parliament. If the Left opposition slowed down legislative business in the last four years, there is no cause to believe there will be an immediate spurt because they are now formally on the Opposition benches. Vinayak Chatterjee, co-founder of infrastructure consultancy, Feedback Ventures, warns, "The government is looking at general elections in the near future, which could mean a significant slowdown in all economic engagements. After elections, the new regime could take up to two years to settle down. This is not good for industry."

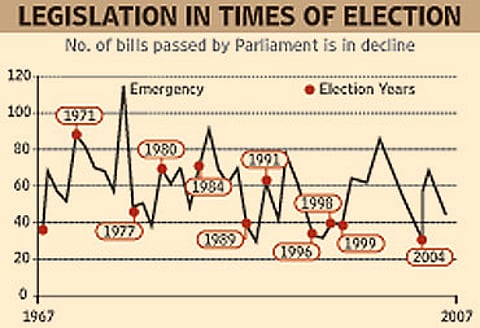

Legislative activity, in general, has steadily declined in India over the last few years. And this is particularly true during election years. "This is because Parliament functions for fewer days," finds an analysis by prs Legislative Research, a Delhi-based research outfit. In 2007, just 46 bills were passed—the 12th-lowest number since 1952. Since 1952, an average of 60 bills had been passed every year. Between 2000-07, on an average, 57 bills were passed a year.

So, what can we realistically expect over the next 6-8 months? Montek believes the implementation of "critical" existing schemes such as the road-building programmes, extending the power reforms, developing healthcare through the National Rural Health Mission, improving the railways, ports and airports, should take up more time of the government until the next polls—and not perhaps the framing of new laws or fine-tuning FDI rules. "In the short run, besides controlling prices, these critical schemes would have the maximum impact on reviving investor confidence," he says.

As for legislation, obviously the government will have to prioritise. Many issues are currently being looked into by the GoMs. At least 12 legislations—including the Rehabilitation and Resettlement bill, a bill to amend rules for land acquisition for industrial projects, the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority bill, changes to the trademark laws, the Factories Amendment bill and Collection of Statistics bill—are pending with standing committees or need to be debated in the houses. Avers Dr Suman Berry, ncaer director-general, "Some of the pending bills, such as the PFRDA, which is holding up the implementation of the new pension scheme for civil services, may get through."

Some changes may be easy. For instance, bankers want voting rights that match shareholding (unlike the current 10 per cent cap). "There is a perceived issue regarding controls, from the unions in this case," says Ashvin Parekh, national leader, global financial services, Ernst & Young. With the Left out of the way, the government may be able to plough such changes through.

So far, the UPA's legacy is the the RTI Act and the 100-days guaranteed employment NREG scheme. Whatever the results, education, healthcare and water resource development have seen an increase in allocations, while there has been investment flows into airport infrastructure. But what remains to be done is equally daunting: woefully, India's weak spots today are still in the areas that were never its strengths. The power sector is one such where reforms have been sluggish despite the push for ultra mega power projects. Infrastructure around ports is improving, but progress is lukewarm. Disinvestments are at a standstill and fresh reforms—such as allowing FDI in retail—are at best moving piecemeal.

Confronted with the task of winning over an electorate grappling with steep rising prices, it's unlikely the government will make a big reforms push. What it will do, many suspect, is be practical, do what's popular. That will rule out a comprehensive review of labour laws or a new look at FDI and divestment. How far this will lift sagging business sentiment is anybody's guess. Do not go by the Sensex's welcome of the Left pullout—it's known for premature celebrations.

Tags