Kali Puja announced, I saw Calcutta

descend on us. Three thousand slums,

usually rapt in themselves, crouched low

by walls or sewer water, now all

ran out, rampant, beneath the new moon,

the night and the goddess on their side.

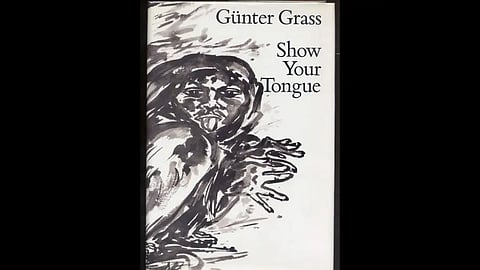

Kali As Metaphor: Revisiting Gunter Grass's 'Show Your Tongue'

Kali came in his 1988 book, originally a journal of his Kolkata days, as a metaphor reflecting two major themes - shame and terror.

Saw, in the holes of uncountable mouths ,

the lacquered tongue of black Kali

flutter red. Heard her smack her lips:

I, numberless, from all the gutters

and drowned cellars, I,

set free, sickle-sharp I.

I show my tongue, I cross banks,

I abolish borders.

I make

an end.

(From Gunter Grass’s long poem, Show Your Tongue, in the book of the same title)

In July 2022, a poster of a person dressed as goddess Kali smoking a cigarette -- from Leena Manimekalai's latest film, titled Kaali -- apparently outraged a section of Hindus, who claimed the depiction of the goddess in the poster hurt their religious sentiments. There has been demand for her arrest, FIRs have been lodged at police stations, and the Indian high commission in Canada, where the filmmaker is currently based, reached out to the local authorities to ensure the film is not screened there.

However, 34 years ago, German novelist and playwright Gunter Grass took much greater liberty in using the deity as a metaphor throughout his 1988 book, Show Your Tongue, the title itself a direct reference to the goddess. The self-illustrated work drew criticism, mostly on account of his portrayal of Kolkata rather than of the city's beloved goddess. It was during the height of the Ram Temple movement in India but nobody seemed to have taken offence to the portrayal of Kali, not at least publicly -- no demand for his arrest or the banning of the book was reported. In 2005, Grass returned to Kolkata as an honourable guest. He faced no protest -- neither for his liberal use of the image of the goddess who has been so terrifying and dear to the Bengalis nor for his alleged ill portrayal of the city.

During his five-month stay in West Bengal with his wife Ute, in the second half of 1986, Grass learnt many aspects of India’s, and especially Bengal’s, social-politico-cultural life, as he travelled and spent time with some prominent intellectuals of Kolkata of the time. But the one thing that evidently influenced him the most is the image of goddess Kali, who came to him as a strong metaphor and dominated the journal he kept. After his return in 1987, the journal was first published in German in 1988 as Zunge Zeigen and was translated to English the next year, published under the title Show Your Tongue.

Grass had built up a love-hate relationship with Kolkata, a city he first visited in 1975. He had announced in 1984 that he will settle in Kolkata for a year after finishing his novel, The Rat. He reached Kolkata in August 1986.

This sentiment is reflected in the following that he wrote in the book, published first in German in German as Zunge Zeigen in 1988 and then in English translation the next year: “She (Ute) had never been here, had never wanted to come. He, years ago, had come alone and, horrified by the city, had wanted to get away. And once away, had wanted to return. (For reasons that became a familiar litany to him, he had long been seeking a precise word for shame.) The horrifying city, the terrible goddess within, would not let him go.”

In his journal, Kali came as a metaphor reflecting two major themes - shame and terror. To him, Kali, “the holy of the holies,” was “sowing daily terror all around her” with her appearance, while her protruded tongue reflected “the proof of her shame.”

“Her sickle raised in a right hand attached to one of her ten arms, Kali, in frenzy, shows her tongue when (perhaps by a shout from the wings) she is made aware that she is preparing to go for the throat of her divine spouse Siva, who, like Kali, is a god of destruction. Showing her tongue, a sign of shame. Since then, Kali has been available in the illustrated form: as a painted clay figure, on shiny posters, ten-armed, ten-footed, often with multiple heads, ditto the tongue. The banner unfurls, showing her colors. While all around her, so the legend, her attendants, ten thousand raging females, are busy winding up the “off-with-their-heads” job, she hesitates, spares the sleeping and, as always, unsuspecting god, allows him to keep the blissful smile of his dreams, and shows her credentials.”

For the first three months, the Grass couple lived at a garden house in Baruipur in the southern outskirts of Kolkata, from where he and his wife used to commute to the city. They sometimes wandered by themselves, sometimes met people, including intellectuals and social workers, visited slums and other marginalised quarters of the society, and attended art and cultural events. Later, they shifted to Kolkata’s eastern outskirts of New Town, closer to the city than Baruipur. The cafeteria at Max Muller Bhavan in south Kolkata became one of their main places to hangout. The couple visited several Kali temples, including the one at Kalighat in southern Kolkata and the one at Nimtala crematorium in north Kolkata.

Grass will meet Kali repeatedly, at temples, streetside idol shops, and household pujas, and the image of the goddess will continue to haunt, interrupt and influence his thinking, every now and then.

Once Grass saw his own head hanging among other male heads – “as pearls in Kali's necklace” – in the “decorative chains that Kali wears as festive adornment, each link a male head.” His head and his companion, Bengali painter Shuvaprasanna’s, of businessmen, tea-shop owners and high-placed bureaucrats – “their eyes filled with surprise and terror.”

Terror came as a major theme in his journal – the terror unleashed by the Indira Gandhi regime in the previous decade and the terror that the Naxalite movement spread, the terror of communal riots, of the Khalistan movement and the Gorkhaland movement.

In his words, “The reciprocal decapitations in Bihar, where people have been joining up with what's left of the Naxalite movement. The carnage among Gurkhas and Bengalis in and around Darjeeling, where our breakfast tea comes from. It is as if under the sign of Kali they are practicing for the ultimate revolution. Sometimes it is the heads of landless farmers, sometimes you see, in news photos, a row of heads from the many-headed family of some rich landowner.”

Her image influenced him so deeply that he saw Kali in everything – in poverty and in the green coconut seller’s sickle; Kali’s sickle overlapped with the hammer and sickle symbol of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), then the ruling force of Bengal,

He even connected Kali’s tongue with the iconic photo of scientist Albert Einstein sticking out his tongue, reportedly being exasperated with journalists.

“His tongue - like Kali's - is excessively long. Quite apart from the panting pushiness of a gang that delights in living off private garbage, it could be that shame likewise prompted Einstein to show his tongue. He and the black goddess together on a giant poster. Or I imagine a conversation in which they exchange experiences on the topic of nowadays vs. Last Days. Site for their chat: Dhapa, Calcutta's garbage dump. Among the garbage children. Crows and vultures above. Both balance the world's accounts, its final increment. A dump truck arrives, unloads. The children search, find, and show them. Einstein and Kali compare their tongues. Photo opportunity. The garbage children laugh.”

At another place, with reference to Kolkata and West Bengal, then under Left Front rule, Grass identified Russian communist leader Joseph Stalin, the Indian nationalist 'Netaji' Subhas Chandra Bose and goddess Kali as “the local trinity.” Speaking of buying posters of three in glossy colour prints, he wrote, “Whenever I lay them out in a row, Kali ends up in the middle. Stalin and Bose, the former in olive drab uniform, the latter in khaki uniform, are wearing medals. While Kali sticks out her tongue, she smiles.”

He went on to comment that “the question of whether a revolution could provide redress will not be answered by Marx or Mao. It will be answered by Kali with her sickle.”

Grass’ book was received with mixed responses. In the 224-page book, 112 pages were his black and white drawings. A review in the Los Angeles Times by Sara Suleri, in 1989, described it as a “powerful meditation” that “unfolds as a document of cultural warning,” exploring the “idioms of indignation and shame that the historic facticity of India generates.”

“When novelists of dignity and repute take brief journeys to countries other than their own, and shortly thereafter produce works that span the genres of travelogues and political commentaries, the results are rarely as distinguished as is Gunter Grass’ extraordinary account of his sojourn in Calcutta. To readers disappointed by the hasty authority of such texts as V. S. Naipaul’s “Among the Believers” or Salman Rushdie’s “The Jaguar’s Smile,” “Show Your Tongue” offers a highly original counterpoint,” the review said.

On the other hand, there were others who criticised his journal as offering a factually incorrect, one-sided view of the city. German journalist and editor Peter von Becker, who had already visited India, described Grass' book in his 1988 review as a “fantastic disaster” and even suggested that because Grass showed little interest in the astonishingly rich cultural life of Kolkata, goddess Kali, as revenge, had robbed Grass of his tongue – that is, his ability to speak and write. Becker's piece was reprinted in English translation under the title ‘The Revenge of Kali’ in ‘My Broken Love: Günter Grass in India and Bangladesh’, edited by Martin Kampchen.

Later, Daniel Reynolds wrote in his research paper, ‘Blinded by the Enlightenment: Günter Grass in Calcutta’, that while Grass represented Germany in the book through founders and followers of the Enlightenment, he represented India through the goddess of destruction, Kali. “It is Kali whom Grass sees everywhere sticking out her tongue, a gesture that he oddly interprets as a sign of shame, but which most accounts link to her fearsomeness and bloodthirstiness as she takes pleasure in the destruction of evil demons,” he wrote.

Kampchen, a German author, translator and social worker, has been living in West Bengal's Santiniketan, the abode of the first Bengali Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, for over four decades, wrote in a piece, titled Now My Smoking Pays Off, about his first experience of reading Show Your Tongue. "I felt, like others in Kolkata, that Grass did neither justice to Kolkata nor to his experience in Kolkata. He was too sure of his judgments, too direct, too simplistic, unbalanced and general in his criticism. He knew too little of Kolkata: not the language, not the history, not the temperament of the people. Even though he wanted to experience all the hardship of a middle-class existence, he being Günter Grass was shielded from many hardships without knowing it."

In his article in ‘My Broken Love: Günter Grass in India and Bangladesh,’ Kampchen said that Grass, “with his no-nonsense style and his strong and adamant views,” was “bound to bruise people’s pride.” “Yet, with a missionary zeal and a desire to be intellectually and emotionally completely honest, he roamed the narrow lanes of Kolkata trying ‘to see it all and tell it all’. His perspectives may have been limited, but his desire, to be honest, was not,” he wrote.

That emotion Kampchen spoke about runs deep through the whole text, perhaps more intensely in the poem with which he ends the book.

“Patience at an end, furious,

on her pile of coconuts mixed with heads,

the heads of Hindus and Moslems

sliced whistle-clean

as blond-eyelashed British eyes looked on,

the goddess, black on Siva 's pink belly,

squats unblinking.”