“I shout because I want to be heard, not as a madwoman in the attic, not as a ghost in a hallway, but as a fellow woman of the world because I will not—I cannot—be otherwise.” -

The Exile Within: The Search For Home In Transgender Poetry And Art

'The etymology of the word ‘Hijra’ can be traced to its Arabic root ‘Hijr’ which means departure or exodus from one’s tribe. There’s poetic justice in the name. All transpersons are in perpetual exile both from the world and from their own body', trans activist and poet Dhananjay Chauhan.

- Gabrielle Bellot, ‘The Isle of Exile: The Definitions of 'Woman' in Global Literature

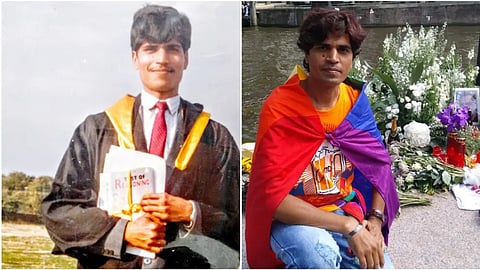

Chandigarh-resident Dhananjay Chauhan feels like two persons at once. She was in class 8 when she first left her home and her family behind to live life on her own terms. Now at the ripe age of 42, Chauhan can recall that though she was displaced from her home in her early teens, her true exile began at age 7 when she first realised she was a girl trapped in the body of a boy. When she told her mother, she was smacked. “Of course you are a boy,” mother said. After all, she looked like a boy. She was dressed and disciplined like one. She was expected to act like one. “But I always knew I wasn’t,” Chauhan says.

The truth came out when Chauhan started participating in Pride parades as a teen. Her conservative Punjabi parents tried everything from incarceration, intimidation, medication and even exorcism to make Chauhan ‘normal’ again. By her mid-teens, Chauhan could not take it anymore. “My family had turned against me, my house felt like a prison. It was not home anymore. I fled”.

Since then, Chauhan has been looking for a place she can call home. But so far, the home has been an illusion. “The etymology of the word ‘Hijra’ can be traced to its Arabic root ‘Hijr’ which means departure or exodus from one’s tribe. There’s poetic justice in the name. All transpersons are in perpetual exile both from the world and from their own body”.

After years of sexual abuse and violence, Chauhan became the first trans student to graduate from Panjab University in Chandigarh. She has two master's degrees and two diplomas. “But no job,” she laughs. But she doesn’t mind. “I have found myself through my work and my words,” she says.

Chauhan is one of the budding community of transgender poets and writers who are slowly filling the literary landscape with their tales of love, loss, identity, othering, and exile. She was recently part of a literary transgender poetry meets organised by the Sahitya Akademi in Delhi this month which features over a score of trans poets from across the country.

“I was adamant that I will not be a ‘Hijra’. I will not wear a skirt and bangles and clap my hands as is the custom among India’s Hijra community. But every community in exile has a way to build identifying markers for themselves. For the Hijras, these customs are important. It’s what helped us survive in a world where we are all perpetual foreigners,” Chauhan tells Outlook.

The perpetual foreigner stereotype was discussed in depth in a paper called ‘American = White?’ which looked at people of ethnic minorities living among dominant majorities like White-Saxons countries such as the United States, where they are inadvertently and always seen as the ‘other’. Further research on the concept showed that the perception or awareness of being a ‘perpetual foreigner’ deeply impacted their identity and their sense of belonging to a country.

“Events like Trans poetry fests, trans film festivals and trans tokenism organised by the cis community largely reflect the aspirations of the cis community in coming across as progressive and as a saviour. In truth, these events in many ways double down on the ‘othering,’” Chauhan says.

She narrates how she has once asked a member of the Sahitya Akademi why no trans poet was invited for their annual literary meet. “He told me, “Tum logon ka toh event hai na alag,” (You people have your own event, right?)”.

In her book ‘Exile and Pride’, author Eli Claire deftly explores themes of alienation among the queer and disabled communities. In the book, Claire looks at how despite gaining acceptance as a dyke among the dyke community, he continued to live with a sense of exile and longed for home. A similar search for Identity and home became was the theme of Mumbai-born Indo-Canadian author Anosh Irani’s book ‘The Parcel’, which told the tale of Madhu, a 40-year-old transgender sex worker in Mumbai’s Kamathipura who lived with the lifelong hope that her family would accept her. The fictional story is more than just fiction. It is the story of many real-life Madhus such as Chauhan who have spent decades living somewhere in the middle.

The theme of exile, from their home, from society, from academia and history and the arts, has featured heavily in trans literary and artworks. While in India, transgender is usually denoted the ‘third sex’ or Indian Hijras, the label, in reality, covers a wide scope of persons within the gender-queer spectrum who do not identify with the heteronormative interpretation of gender. This can include transpersons, transvestites, transsexuals, drag queens, intersex and other gender-fluid identities. In India, many of these identities tend to get lost, even within the trans community. Transmen, for instance, have much lower visibility and hence representation than transwomen. Same with transwomen who choose not to undergo sex-change therapy or dress like women but still identify as trans.

“There are many such writers who identify as trans but have never revealed their truth to people. Maybe they don't have the opportunity, platform or education to express themselves properly. Or maybe they don't fall into the accepted "transgender" category,” says Manobi Bandhopadhyay.

Bandopadhyay, who was the first transgender woman to become the principal of a college in West Bengal (for a brief period before quitting citing discrimination by college administration), however, says that pigeonholing artists as 'trans or queer' is also a form of othering. The feeling of exile, she points out, is universal to all poets and artists. "We all write from our own experiences of not belonging, in the skin or in thought. Rabindranath (who I believe was himself transgender) wrote, “Kothao amar hariye jawa nei nei mana, mone mone”. I think all poets live in a kind of exile from the world," she says.

Bandopadhyay who chaired the first Trans Poetry meet held in West Bengal in 2018 and has since been part of these annual summits, says that while it is important for trans people to find a sense of belonging, such events often miss out on the full spectrum of trans identity. "People who come out as transgender invariably consider their abandonment or exile from the hypocritical 'civil society'. It's like swallowing a bitter pill," she states.

"My 31 years of working life were spent in exile far from my home. I still work in exile!," she adds.

She points out that not all poems written by trans poets are about exile or displacement. Some poems are about the inner conflicts of the trans experience. Some are about the irony of promoting Beti Bachao Beti Padhao while ignoring transphobia. "Trans poets also write about topics that cis poets write about. But no one wants to read that," Bandopadhyay rues. Bandopadhyay herself chose to read out the following lines at the 2022 summit: "I wanted love from you / You gave me huge condom full of my both hands and KY gel".

Displaced from self

In the book ‘The Parcel’, the protagonist Madhu’s character undergoes not just physical exile but also a sense of displacement within her own body. Thus the body becomes a central character in most trans narratives about self and identity. While trans poets try to represent the disconnect between their bodies and minds through themes like exile, others use the body itself to create art. Trans body-builder and body artist Heather Cassils’ phenomenal works of performative art feature his own female body, metamorphosing into works of introspective art. In his 2013 performative art project ‘Becoming An Image’, Cassils created a 2,000 lb sculpture, dragged it to a dark venue packed with people and attacked the sculpture with brute force until it broke to an unrecognisable shape - debris of mortar. The 20-minute performance took place completely in the dark, illuminated only by camera flashes and thus searing burning yet fleeting images of Cassils attacking the mutilated stone upon the minds of all those watching. The idea was to draw attention on the brutality of violence faced by trans bodies. On yet another level, it reflected the fleeting space they get in public discourse. In Cassils’ case, the artist was able to interpret the displacement he felt with his body to represent larger issues that plague transpersons and their physical safety.

Even for trans artists not working directly on themes specific to trans identity, the search for home remains a near-constant driving force. Growing up in the trans community of Mumbai, dancer and trans activist Abhina Ahir saw trans life very closely. She saw them commit suicide, or abuse substances to escape their reality. There was also a lot of self-stigma and self-loathing in the community.

To provide young queer people with a sense of belonging and purpose, Ahir started a group of dancers called ‘Dancing Queens’ 19 years ago.

“After our first show, we saw some transgender people cry. It was the first time they had seen transwomen dance not at for money at someone’s wedding but on stage.” Today, Dancing Queen performs heavily on themes related to the Indian film industry and Bollywood. From shows featuring different dance forms of India to different film directors and tributes to actors, Dancing Queen lives and breathes Bollywood.

Ahir, however, rues that it would be nice if Bollywood returned the favour and gave them the same kind of representation. “There are some transgender artists like Ghazal Dhaliwal who are bringing something of the queer experience to the mainstream. Films like Badhai Ho and others have started talking about trans people. But there are still no trans actors or popular trans faces in the industry and films continue to stigmatise the trans identity”.

In the 80s, Manobi Bandhopadhyay who spoke to Outlook started a magazine called Abamanob (Sub-human) to reflect the stories and lives experiences of the trans community. The title of the magazine reflects the search for the trans identity in a world where difference is not considered human. To this day, transgender persons in India face atrocities and are victims to inhuman, oppressive and discriminatory acts. Despite a law that recognises transgender as the ‘third gender’, the lives of ordinary trans people have remained unchanged. “The legislation has given us the right to exist but the country is still hostile to the needs of trans people. In the end, the onus to find a home for oneself and safe spaces remains on the trans community itself,” Dhananjay Chauhan says. As of now, the activist remains busy with her advocacy and her fight to bring in gender-neutral toilets across Indian educational institutions. “While the exile within is personal, the exile from out outside world is social, economic and political. It can be reversed only through awareness and activism,” Chauhan says.

Tags