Aptly dubbed the year of global elections, in 2024, people in many countries have already exercised their right to choose their governments, and many will follow during the remaining months. The already concluded elections included a pantomime in Russia to elect Vladimir Putin to another six-year term as president, with a promise of another term through 2036.

Indian Inequities Beyond Elections

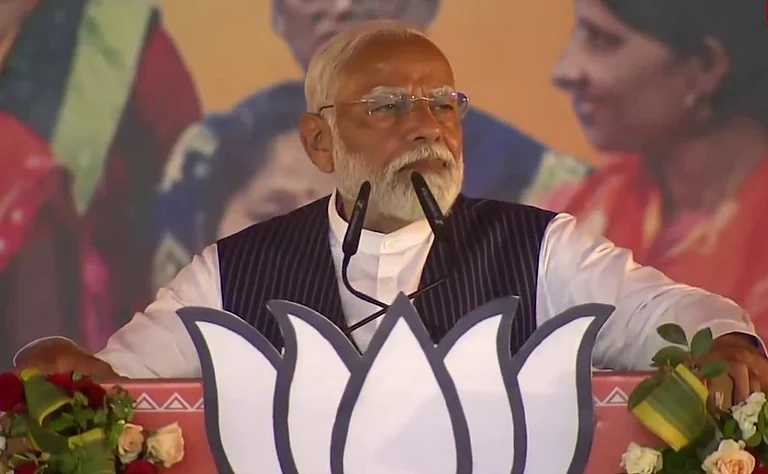

Whether Narendra Modi wins again or there is a change of guard, addressing structural inequities in the system will require more than the outcome in a single election

Despite absolute power, strongmen never leave anything to chance, nor did Putin; his fierce but jailed detractor, Alexei Navalny, decided to die in the Arctic penal colony days before the elections. The never-ending Presidential hustings in the United States will culminate with polling in November. That election’s outcomes will determine the future of democracy in the US and elsewhere. Meanwhile, the world's most populous country, India, is amidst protracted polls to elect a new government. Within the conflicted opinions and contradictory reports, the consensus mostly settles in favour of Modi and his party retaining power for another term. Though, by the very essence of democracy, by now, anti-incumbency fatigue should have set sails against the Modi government's chances of re-election. Towards the end of its second five-year term in 2014, the last Congress party-led Indian government had come apart at the seams, which in part heralded Modi to power despite his less-than-savoury past. However, Modi is no ordinary politician; he has already carved his niche among the authoritarian leaders who, for different reasons but with a singular purpose of absolutist power, have curtailed democracies in their respective countries. Modi's elevation to an ethereal godfather-like figure in India is complete, with no other pretender allowed in sight. Such is his domination: there is no party, no government, and just Modi. Though not unprecedented, such an absolute and constricting stranglehold on power is no accident; instead, it resulted from carefully orchestrated manipulations at different levels in multiple dimensions. Ever since coming to power in 2014 with a smothering majority, Modi and his party have altered the political discourse and landscape in the country, which became more acute after an even greater mandate in the 2019 elections. Throughout his time as prime minister so far, he never wavered from his extreme nationalism, schismatic ideology, and rabid agenda and has torn away whatever form of secularism Indian politicians of different hues would profess.

Despite the veneer of a government with an inclusive agenda, Modi, in the past ten years, virtually presided over the dismantling of the pluralistic society, erosion of the state institutions, downright degradation of the parliamentary democracy, unleashing of cronyism of the worst types, demeaning of minorities, and degradation of media to the point of depravity. Anyone familiar with Modi's past would hardly be shocked by those retrogressive developments, a past that hardly merits mentioning all over again. His hubristic functioning style always latches with intrinsic cruelty, informing his governing and decision-making. The most consequential decisions, whether rendering people's money worthless, shutting down the country in response to the pandemic, or stripping away a state's autonomy, all caused immeasurable human suffering and cost lives.

The demonetisation announced in November 2016 without sufficient notice caused the instant destitution among millions, which was called by Steve Forbes “a massive theft of people's property without even the pretence of due process.”

A similar cruelty-laden move culminated in shutting down the entire country in the early summer of 2020 without a prior warning with a diktat from Modi when India had reported slightly over 500 cases of COVID-19 infection. That wrought unimaginable miseries on the poor of the poorest working on urban mega projects and barely surviving on their daily earnings. Bizarrely, when a year later, a mutated form of the coronavirus brought havoc on the country; with patients grasping for the lack of oxygen and the dead suffering ultimate indignities for the lack of proper cremations, the Modi government suddenly went awol. Like strongmen throughout history, Modi, despite his perpetual supercilious demeanours, betrays deep insecurities at the slightest scrutiny. That weakness becomes acute in the run-up to elections at every level. Instead of asking for a continued mandate based on his government's performance, Modi tends to descend into appealing to the worst majoritarian instincts and demonising the minorities, railing against imaginary historical iniquities, bloviating against the opposition parties with ludicrous innuendos.

Otherwise, the woefully proudest Indian leader, who never tires of boasting about achievements under his stewardship and downgrading his predecessors, Modi reduces electioneering to a virtual race to the bottom, shredding all sense of decency and purpose.

While campaigning during the 2019 elections, in which Modi was the favourite to win and did ultimately prevail with a commanding majority, he frequently indulged in senseless rantings and self-pitying. Before that, during the provincial Gujarat elections in 2017, he descended into hurling an accusation at his predecessor, Manmohan Singh, of conspiring with neighbouring Pakistan to alter the outcome. Modi's lowest moment came during the 2021 provincial elections in Bengal, with his party pitted against the regional outfit government headed by indomitable Mamata Banerjee. At an election rally, he repeatedly whispered Ms Banerjee's colloquial nickname. As puzzling as it might be, Modi's behaviour and conduct during the elections tend to lull the political opponents into complacency, only to wake them up to the rude reality of a country that has gone far too far in the direction of parochialism. As a psychologist, Modi perhaps understands that appealing to majoritarian insecurities is more rewarding than discussing complex developmental issues; or possibly more than anyone else, he is aware of the gap between the promises and deliverance of his government.

Modi did not create such an ecosystem of moral void with his constituents supporting him for his exploitation of their irrational gullibilities. Such a void in the system had been in the making for a long time that paved the way for unscrupulous operators like Modi to swoop in and expand its boundaries to the point of no return, leaving little room for reason or rationality.

Perhaps that explains why Modi and his party ultimately win the elections that matter. Suppose Modi emerges victorious again in the ongoing polls with his diehard fanatics' undying support; how would his win square with the performance of his one-decade-old government? That merits the question of whether his government is a resounding success, as his sectarians would have everyone believe, or it is a story of an abject failure, a common refrain of his detractors. Based on the opinions of independent analysts, most point to a mixed bag with many missed opportunities and misdirections due to hubristic tendencies of overstatements, overestimations, tragically asymmetric priorities, and capriciously opaque decision-making. In a revealing interview, Dr Raghuram Rajan, a University of Chicago-based economist who also served one term as chairman of the Reserve Bank of India under Manmohan Singh, noted that while the Modi government vastly boosted investment for infrastructure development, it egregiously fell short in developing and investing in human capital.

The lopsided policies led to an acute problem of youth unemployment, which ultimately will stymie the overall growth and development in the long run. Not to underestimate the dangers of a vast pool of unemployed young people falling prey to an extreme religious ideology, which might already explain many of the self-perpetuating tidings in the country with Modi's party as the ultimate beneficiary.

The actual beneficiaries of Modi's policies, the rich of the richest with exponential growth in their wealth, form his natural constituency. With the overall increased girth of the Indian economy, Indian visibility in the world has increased more than ever, which shields the government from international opprobrium due to diminishing democracy, increased authoritarian tendencies, and institutional erosion in the country. Recent reports also point to the Indian government brazenly indulging in targeting dissidents in the neighbouring countries and beyond, including in Europe and the Americas. In the summer of 2023, while President Biden had laid a red carpet for Modi at the White House, the agents of an Indian intelligence agency were allegedly busy arranging the elimination of a US resident, a supporter of the Sikh dissident movement.

Various international nongovernmental organisations have already flagged the concerns plaguing the democracy under Modi's one-decade-long rule. Based in Sweden, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, in its report, had already 2018 downgraded India to an electoral autocracy and stays there in the lower rung among the different countries in the world.

In the international press freedom index, India stands at 159, three spots higher than Russia. Despite such disquietude, glaring shortcomings, and the burden of incumbency, the consensus among analysts is that Modi will prevail in the ongoing elections for multiple reasons.

One of the astute political thinkers enumerated the pillars on which the ruling party's success hinges: an unabashed promotion of extreme Hindu ideology, populist welfare schemes, and the money juggernaut of Modi's party that remains unmatched in breadth and depth. One can add to that list the muscular use of investigative agencies against political opponents and the obliteration of the independence of the state institutions. More than anything else, the factor that favours Modi most is the absence of a credible and cohesive political opposition. India's political opposition presents a fragmented outlook with multiple regional outfits with outsized ambitions, narrow interests, and outdated ideas. The only national political organisation, the Congress Party, which had ruled India for almost 55 years, is virtually caught in a static whirlpool of its contradictory past of neoliberal governance and socialistic ambitions. The contradiction still hampers the party, for that matter, the entire Indian political opposition conglomerate from embarking on an inclusive agenda to contrast them with the narrow majoritarian program unabashedly pursued by Modi and his party.

The Congress party suffers from an inherent weakness of being centred around a single family, making it vulnerable and open to accusations. It already contested two national elections under the scion of the Nehru-Gandhi family, Rahul Gandhi, with abysmal results. While a thoroughly genial and kind-hearted person, many doubt his capability to endure the rough tumble of the contact support that politics is, his political acumen, and his uninterrupted commitment. In his memoir "A Promised Land," Barack Obama compared Gandhi, whom he met in 2010, to "a student who'd done the coursework and was eager to impress the teacher but deep down lacked either the aptitude or the passion for mastering the subject." While Modi's detractors remain nostalgic about the Congress party, it is pertinent to remember that the political outfit is far from the one that led the freedom movement against the British through 1947. The broad-tent party underwent many metamorphoses and divisions throughout the years, with the Nehru-Gandhi family forming the nucleus for the largest rumps.

Nevertheless, the party in many parts of the country still garners a share of votes comparable to Modi's ruling party, albeit it mostly fails at the finishing line. More than anything else, the party is dwarfed by the utter lack of clarity of purpose and vision. However, the party, in alliance with other opposition parties, can potentially knock the ruling dispensation out of power, provided it comes with an aspirational program of an inclusive future instead of regurgitating promises of the last century.

Many in the Indian opposition remain nostalgic about the pre-liberalisation era with a controlled economy that had kept entrepreneurial possibilities locked in bureaucratic dungeons. Moreover, a strange coalition cobbled by the opposition parties to take on Modi jointly has come with a convenient flexibility for one constituent to indulge in recriminations against another for political expediency, hardly a confidence-building or a winning strategy.

If the Indian opposition parties fail again, which looks likely, democracy will, in all likelihood, become shakier than ever before. Part of the reason for that bleak outlook is the Indian population's commitment and understanding of democracy and democratic processes. In almost every survey, an overwhelming majority indicates a preference for an authoritarian government for the country. India was one of the few countries where Donald Trump had legions of supporters and admirers, mainly because of his anti-democratic, xenophobic, and authoritarian views.

Trump, to this day, poses an existential threat to democracy in the United States and elsewhere. Adulation for the eternal Russian dictator, Vladimir Putin, into his 24th year of reign cuts across the political divide; a majority of Indians across the political divide became vociferous supporters of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Some of the leftist politicians in the country exultantly congratulated Xi Jinping for virtually appointing himself to the Chinese presidency for life, and others have children named after brutal Soviet dictator Stalin. Ironically, the people who harbour profound scorn and disdain for the democratic West also clamour for places in European and American universities. Tragically, even during their stints in Western institutions, many fail to grasp the deep democratic traditions and freedoms prevalent in liberal societies.

Right at its inception in 1947, India opted for democracy with an unwavering commitment to the constitution drafted through meditative deliberations. The establishment of independent institutions provided guardrails that allowed the nascent democracy to establish deep roots. Jawahar Lal Nehru, as the first prime minister with his liberal Outlook, helped to entrench the democratic traditions despite incredulous challenges, including a perilous war and stitching together a country fragmented into semiautonomous princely fiefdoms.

More than Nehru, the galaxy of talented politicians with differing philosophies, fresh from the freedom struggle, laid the foundations of an idealistic state as a shield against obscurantist forces of religious fundamentalism. Nehru developed his vision of a scientific temperament by creating premier centres of excellence and a planned economy that entailed investments in massive projects to change the country's trajectory.

Nehru's inspiration came from the outwardly pristine Soviet experiment of a controlled economy sans the dictatorship of the proletariat. Besides constraining free enterprise, the severely regulated, top-heavy, and bureaucratically managed development model paved the way for the future resurgence of the reactionary forces that the founders had actively sought to neutralise. The heavy investment into audacious mega projects and centres of excellence set the country on the road to modernity. Unintendedly, such developmental expeditions came at the cost of neglect of an overwhelming swath of the country and population. In education, the government established outstanding centers in the form of Indian Institutes of Technology in four metropolitan areas that, in recent years, were also extended to other cities: Delhi, Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta. Those centers with extremely restricted entrances became islands of elitism and smugness with a gap of almost the entire universe between inside and outside their perimeters. While those chosen centers attracted enormous resources for providing nearly free training and highly subsidised food and lodgings, multitudes of universities and other educational institutions across the country suffered from criminal neglect and lack of resources.

The graduates from those premier centres of excellence became fodders for American institutions and technical companies. The myopic Indian establishment never had a vision of committing the graduates trained at staggering costs to fan out in the countryside for development at the grassroots. Instead, the much-touted Institutes became wormholes for brain drain and resources of talent for the developed world. Otherwise meager in number, those premier institutions with inflexible admission requirements resulted in a culture of cutthroat competition and spawned unscrupulous coaching centres that inculcated young minds with the mantra of success at any cost without concern about the means, thwarting independent thinking. At the same time, the ordinary universities, colleges, and schools in the country at large suffered near absence of funding, resources, and nurture, thus failing in the primary task of imparting decent education and neglecting civic training. The poor investment in human capital mainly emanated from the unimaginative centralized political model, which failed to germinate a democratic culture at lower levels.

The governance at the unitary levels ended up in the hands of unimaginative and inflexible bureaucracy that assumed unchecked disproportionate power and became a fountainhead of corruption. The lure of bureaucratic positions became so overwhelming that even the reputed universities to this day tout the number of top officials produced rather than the scholars of any repute or worthwhile academic achievements. More than anything else, the failure to spawn a democratic culture at the grassroots, in villages, small towns, and cities across India, and without informing the public of the true meaning of democracy and factoring in the conservative sensibilities came at a high cost.

The Indian constitution, though drafted deliberatively, lacked indigenous philosophical underpinnings, resulting in the population at large in the country, unlike the Western societies with no grounding in categorical imperatives, misconstruing democracy as a free-for-all phenomenon without responsibilities. Everything became purchasable, and the land drowned in corruption at every level and of varying scales. The public officials assumed the mantles of medieval oppressors, who mistook their routine public functions as acts of munificence. The dearth of education aimed at humanitarian development at the basic levels gave way to the obscurantist sectarian divide that grew worse with time. The repeated declaration of secularism in a society steeped in deep religious traditions became counterproductive for exploitation by reactionary forces. The politics in India represents a typical case without a philosophy, and as Zadie Smith put it in a different context, unmoored, unprincipled, which holds as its most fundamental commitment its perpetuation. Far from confinement to bureaucracy, the feudal outlook prevails in India at many levels, starting from average homes with rampant exploitation of personnel engaged as household help. The electorates in India have already made their choice in half of the country, and in less than a month, the future direction will become apparent. Whether Modi wins again or there is a change of guard, addressing structural inequities in the system will require more than the outcome in a single election.

(views expressed are personal)