The Water Lily, Drooping

Sea The Change

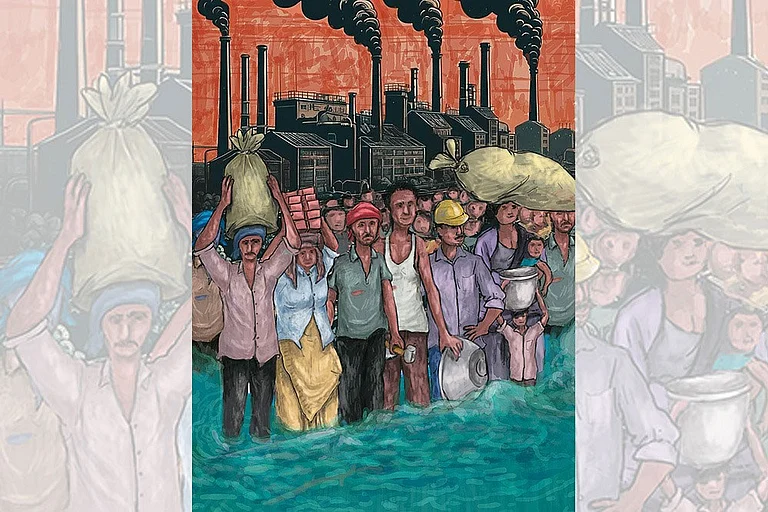

This piece is an outcome of my struggle to comprehend the times I inhabit. They are based on encounters in a fishing village near Pondicherry (Puducherry), where fishermen friends helped/are helping me navigate new waters. The ever-changing sea led me to these explorations. There is urgency in the air. Else, all will be still

The sea—a constant landscape. A universal space, unchanging, steady on the horizon. A basis of life on the planet. Meditative. The unending breaking of waves on the shore, or the soft lapping of waters away from it, suggest deeper reflections. The unfathomable and inaccessible depths hide unsolved mysteries locked within, possibly since the beginning of time itself. Fluid grounds.

The view from the long stone groyne, jutting more than 30 m into the sea, facing the pre-dawn sky as it lightens up, the endless horizon and the unknown cosmos appear as ideas in themselves. The twilight stars link the universe to the earth. It lies somewhere outside the edge of the stone jetty, boundless, fear-filled, and without beginning or end. It is a time for superstition, and wonderment. The time scale is galactic, and mortality a mere meaningless blip.

Behind, on the shoreline, the row of fishermen’s houses affords no time for such introspection. Life is material and harsh in its everydayness. Until recently, this is where the fishermen lived. Now, many have sold the beach-facing houses to outsiders. The view of the sea is stunning, especially on a good day. Huts have been transformed into nice whitewashed homes, pretty and reflective of a good life. The surfers are testimony to that. The village now stretches behind this row, where the fishermen still live.

Ancient Tamil Sangam poetry identified landscapes with views of nature. Akam and Puram—interior and exterior. In Akam, the sea—Neithal—denoted the pain of waiting and pining for the loved one. ‘Nature’ was internalised. The separation was there, but incomplete. Fade in—fade out.

In contemporary times, nature must be acted upon. Now it is a ‘view’, or an ‘adventure’, or a ‘resource’. Without this operative relationship, we are lost. Not the fishermen though. For them, the sea is the lived life.

As ‘fish’, ‘storm’, ‘boat’, ‘net’, ‘livelihood’ or ‘longing.’ The landscape is internal as well as external. Akam and Puram, as in ancient Sangam poetry. The divide is now complete. Freedom and isolation go together.

With Petals Closed

The beach. Lined with boats. There are two distinct types. Those with outboard engines, and long propeller shafts, rudders, and others, hand-powered by broad wooden rectangular paddles. Power and propulsion depends on who owns them, and their economic status. Access to technology is not democratic. Capital overshadows labour. For some it is eternal labour. There is no escape.

The flat, human-powered boats are made of fiberglass. A decade ago, they were made of softwood. Merely six long pieces of wood lashed together with rope. And then three more of upturned wood, to form a keel. Impossible to sink, heavy, soaked water, but no repair required. Today they lie scattered around beaches, broken, unused, as junk. Disuse and disrepair. Replaced by industrial fiberglass post-disaster, post-tsunami, along with the diesel engines.

Technology and capital have come together to change the idea of ecology itself. A lived reality ecology has become a ‘desired’ space. Those who have the money can aspire to the ‘nature experience’.

Two propelling devices, two economies. One boat costing a mere Rs 15,000, while the other Rs 15 lakh. With a diesel engine, a big net, the figure goes up to Rs 25 lakh. Technology allows selective access to the sea. A small boat travels 2 km, while the powered one, over 20 km. Every day, without fail. The fish catch is bigger, the nets trapping everything that moves. Fish as well as non-fish. The smaller boats have to be content with a smaller catch. Leftovers. Worth maybe Rs 200-Rs 300 daily—if that. When the seas are rough, the small boats stay at home.

Eternal labour, but even that is not guaranteed!

The dream of a larger boat, with a diesel engine, keeps the fisherman going. One way is to sell their beachside hut facing the sea to outsiders, and live in a smaller home inside the village. Those with such land allotted to them after the tsunami, did that and invested in larger boats—often jointly with other fishermen. Others, without such assets, toil on. Fishermen village to beachside retreat! All live inside the village, behind the fancy houses. They sleep on the beach. The sea breeze is cooler than inside and the familiar sound of the sea beckons them. Like always.

Technology in the form of a diesel engine is changing the landscape of the village. Technology and capital have come together to change the idea of ecology itself. A lived reality ecology has become a ‘desired’ space. Those who have the money can aspire to the ‘nature experience’. The fishermen only live on, off and in it.

Resembles the Body

Then there is the new port nearby. Desired by politicians and others who wanted to be known as the modernisers of a sleepy coastal town; it was built despite all reason. No one asked the fishermen. Possibly, as whispers go, there were lucrative contracts hidden in the sand. Who knows! Yet the small seaside town was never a big industrial hub, nor did it have a huge amount of commercial shipping. So who was the port for? However the port was built. A huge wall and jetty were constructed. Artificial harbour. As predicted, the sand from the estuarine river close by—and it was in millions of tonnes each year—could no longer flow. Normally it deposited onto the seashore, to form the beaches. The fishermen lived and parked their boats on them. Without the sand, they may as well pack up and go home. The port stopped the sand from flowing along with the coastal currents onto the shores. Millions of tonnes of sand piled up on one side of the port wall, as the beaches waited and waited, pining away, thinning down. The sea eroded the beaches even more, and soon the water was lapping up to the fishermen’s huts. No place left to launch the boats.

The desperate fishermen went to town, fearful of a loss of livelihood. This is all they knew, the only skill they had. In a knee-jerk reaction, the politicians decided to act. Only to worsen the situation. Making long stone jetties along the sea, to protect local coastlines, they changed the currents even more. Uncertain consequences! In some places where there was already substantial erosion, they blocked off the shore with large stonewalls. The walls became garbage dumping points. The stone jetties managed to stop some local erosion, but the sea was unstoppable. It just went ahead and ate away the sand beyond where the jetties ended! Surprised?

With no fresh sand coming in from the river, it was a domino effect of disaster!

As they say, ‘when a butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazon, it causes a storm across the world’. That is how much we really know how ecology works!

Politics has a five-year time frame, human life a hundred, but ecology takes its time—it could take 10,000 or even 100,000 years, or more.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Sea The Change')

Ravi Agarwal has an interdisciplinary practice as an artist, writer, curator, and environmental campaigner