An Evening With The Bhuttos

<i >Outlook</i> meets the young Bilawal, Benazir's 18-year-old son, in Dubai, and finds out what it means to be a future heir of the Bhutto legacy

Bilawal was then just a baby. The family was staying at Sindh House, waiting for the Prime Minister's House to be prepared. Careening up Islamabad's empty roads, past security checkposts and guards, heading into Sindh House, was a jeepload of armed men who looked like Afghans. Bilawal was being wheeled outside in his pram. Benazir recalls, "The jeep had no number plates. It was coming straight towards him. It could have all been over in seconds. They could have snatched Bilawal and Allah only knows what would have happened next. But some instinct for self-preservation must have come over the woman who was taking care of him. She scooped him up and ran indoors." An inquiry into the incident predictably came up with no leads.

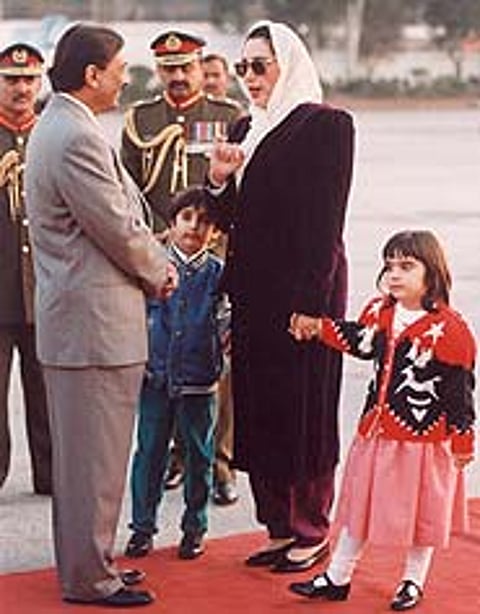

In fact, Benazir and husband Asif Ali Zardari's children have lived in exile for most of their life. It began when they were spirited away to London as babies in 1990. Bilawal, then two, and Bakhtawar, not even a year old, were in the care of Benazir's sister Sanam and Zardari's parents. But Bakhtawar, who didn't stop crying for weeks, had to be brought back home by Benazir at the height of the political crisis in the country after her government was dismissed. In 1996, soon after Murtaza bled to death after a shootout yards away from their Karachi home, Nusrat insisted on taking them to London, and to safety. In September that year, she arrived in Dubai with the children. Benazir joined them in 2000, the children cocooned from the political uncertainties of their homeland.

"I've made many friends here and Dubai has grown on me, I like my life here," says Bilawal. His surname means little to his fellow students, and the measure of anonymity helps him concentrate on his studies. Yet, asked what he remembers of Pakistan, he says the memory of "thousands of people shouting slogans in support" of the Bhuttos persist, drawing him to his country's people in an overwhelming way.

"But it's too early for him to take part in politics," protests protective mother Benazir, as she proffers chocolates and cups of steaming green tea. Juggling overseas calls from journalists who scent the change in Pakistan, Benazir is completely clear that whether or not there's a deal with the military, at no point will her children's safe haven here be jeopardised. "As a mother, it's my duty to protect my children; their education is a priority. Even though I come from a political family with a strong sense of duty to my country, I'd strongly advise them to stay away from politics, to serve the country in other ways. As a doctor, a social worker, anything."

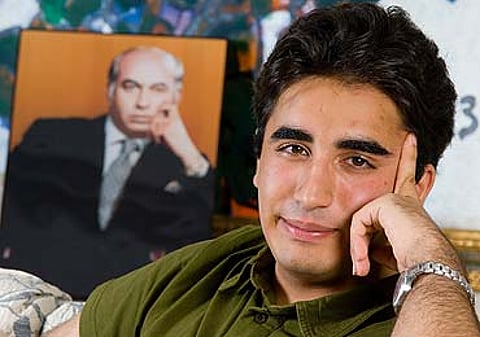

"But I'd like to go back to Pakistan to vote," interjects the young man with an uncanny resemblance to grandfather Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in his youth, whose portrait as prime minister dominates the living room of their home. "I'd like to participate in an election that brings true democracy to Pakistan. I hope this time it's an election, not a selection," says Bilawal. Indeed, reports that he had received a voter identity card set off fevered speculation that he will be by his mother's side when she makes the epic journey home, even throw himself into campaigning for the family firm.

But with his eye not so much on the political ball as much as on the world of academia, Bilawal, who graduated from Dubai's prestigious Shaikh Rashid School last week, is heading for college in the UK. His choice of history as a subject of study—"one has to study the past to understand the future"—is no surprise. "He's a lot like my father in his ability to marshall facts to present his argument," says Benazir. "He's also so much like Mir (Benazir's brother), the same sense of humour, the same quiet wit."

Out of the country, the Bhutto children were as much a victim of the pressure tactics as their mother when the authorities would play them like a yo-yo, holding out the prospect of a release for Zardari, only for fresh charges to be filed. "Each time a case against him would be dropped, our hopes would rise, we'd be convinced he would be freed, that we'd be a normal family again. There was one point when the court dropped all the charges against him and I told my mother he would be out, but she said wait and see, don't get your hopes up. And just as she predicted, a new case was filed against him," recalls Bilawal. It was back to square one.

Not surprisingly, the young man, not given to smiling among strangers, was beaming when he and youngest sister Aseefa walked out of Dubai airport with their father, he a free man at last. "When I look back at the moment, I can't really put a finger on the overriding emotion. It was relief, definitely, but it was also kinda hard to believe it was happening, it was unreal. " Then, in 2005, it was Bilawal who ushered me into the waiting car for an interview with Zardari as we raced to the Bhutto home where the excitable Bakhtawar, eyes streaming with tears, burst through the gates and enveloped her father in a bear hug.

Bilawal, who signs his name Bilawal Zardari rather than Bhutto, nods his head vigorously in approval when I point out that Priyanka Gandhi had recently asked journalists to call her Priyanka Vadra rather than by her maiden name. Asked if there was a conflict of interest over being a Bhutto or a Zardari, he says: "I'm very much a Zardari but there's no question, I am also the son of Benazir Bhutto, grandson of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. To my mind, there's no conflict, I draw from the heritage of both, one strengthens the other." Spoken like a true politician.

Bilawal is equally circumspect about the rumoured split with slain uncle Murtaza's daughter Fatima, 25, the only child apart from uncle Shahnawaz's daughter Sassi bearing the Bhutto name. Given the widows' marked antipathy towards the family (Murtaza's widow Ghinva laid claim to the Bhutto home in Karachi—70, Clifton; Shahnawaz's widow Rehana was suspected by the family of poisoning her husband), Fatima or Sassi, or both, could some day be primed to lay claim to the family legacy. "But there is no rivalry," says Bilawal.

That rivalry is for the future. Currently, the former first family of Pakistan is at the crossroads because of Benazir's decision to return home. "For years, given the situation in Pakistan and the needs of my family, I've run the party from exile, but I believe I'm needed now in Pakistan, my place is there among my people, at home. It's time to go back," says Benazir, heartened by independent pollsters who say she is more popular than President Pervez Musharraf.

As Benazir prepares to pack her bags for home, the unspoken fear in the Bhutto home is that she will be at enormous risk. Says Benazir, as the young Bhutto inheritors exchange glances and fall silent, "The children have told me they are very worried about my safety. I understand those fears. But they are Bhuttos and we have to face the future with courage, whatever it brings. A long time ago, I came to the conclusion that life and death are in the hands of God. That lesson from my father has stayed with me to this day." And will continue to be put to test in the days to come.

Tags