December 7, 2016, saw the 75th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 8 in East Asia, thanks to the international dateline). The occasion was marked by visits of veterans to the site in Hawaii where World War II in Asia exploded into open conflict between the United States and the Empire of Japan. The sombreness of the occasion was made deeper by the knowledge that this was almost certainly the last commemoration that would be marked by the presence of living figures who remembered the days of the Pacific War. Yet, while distance has robbed us of most of the eyewitness accounts of that war, it has also enabled historians to come to some broader conclusions about its wider causes and meaning. One particular factor has come to the forefront of blame in recent years: the idea that mutual mistrust and misunderstandings helped drive two of the world’s great powers into open conflict in 1941. Make no mistake, the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and Tokyo’s increasing desire to close off trade in Asia to any actors other than Japan were the key factors in forcing confrontation. However, examination of the diplomatic cables that show American and Japanese assessments of each other show that neither side really understood the other’s concerns on issues varying from maritime defence to free trade in the region. Eventually, those misunderstandings helped provoke a brutal war.

Anything But Pacific

The Asia Pacific’s future hinges on nuanced Chinese strategy and the unknown factors of a Trump presidency

Historians may look back at the past few weeks and wonder whether a similar set of mutual misunderstandings could trigger a serious regional conflict between the US and China. The likelihood of such a confrontation is still, mercifully, far lower than was the case in the 1940s. But both the US and China run the risk of exacerbating the one factor that, above all, could create a crisis in East Asia that would spill over to the rest of the region and the world: unpredictability. Both are sending out mixed signals that make it unclear how regional partners should engage with them to create a zone of mutual trust and prosperity.

This naval battle fought in the Arabian Sea and won by the Portuguese against a combined fleet of the Gujarat Sultan, Mamluk Burji of Egypt, Zamorin of Calicut and supported by the Ottomans, the Venice Republic and the Ragusa Republic was crucial for taking over the Indian Ocean trade route from the Arabs and the Venetian control.

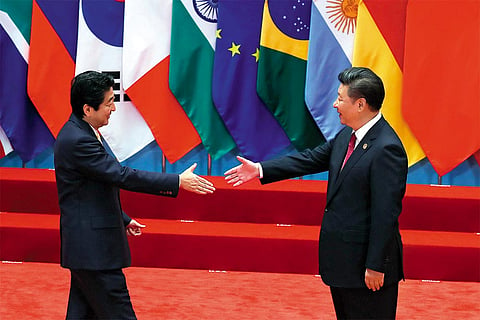

Until recently, it was China that appeared to have the more serious case to answer. Between 2012 and 2015, China’s regional diplomacy was marked by assertive and often belligerent-sounding rhetoric, sometimes matched by actions. For several years, China raised the temperature with Japan over the islands in the East China Sea known to the Chinese as the Diaoyu and the Japanese as the Senkaku. Menacing encounters between warships and fighter aircraft on both sides led many to worry that a local incident might quickly explode into regional conflict. A sort of cold peace between Chinese president Xi Jinping and Japanese premier Shinzo Abe was agreed when the two shook hands at the APEC summit in November 2014. However, the past two years have been marked by increasing Chinese activity in the South China Sea. Despite Chinese assurances that they do not intend to militarise disputed reefs and islands in an area vital to international shipping, there are increasing signs of a build-up in those areas that gives neighbours such as Singapore, Indonesia and Vietnam seeming reasons for concern.

However, the past few weeks have seen two major developments that have the potential to change the dynamic in the region. One is a growing sophistication in Chinese strategic diplomacy in the region. The other, of course, is the election of Donald J. Trump as the next president of the United States.

Pearl Harbor led to a devastating war in the Pacific that ended with Japan’s defeat and the establishment of an order in the region that proved much more lasting than many would have expected in 1945. Over the years, stability in the Asia Pacific region became dependent on three factors: the establishment of regional actors, notably ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations), who created networks that helped stabilise the region; stronger bilateral security and trade relationships; and underpinning it all, the assurance of the US that it would support its allies. There were major changes in this structure during the years of the Cold War and after, most notably, the reintegration of China after 1971, but these broad pillars were at the heart of the region’s relative peace and stability.

Day of infamy: A photo that stands testimony to the shock of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

China has come to realise that its growing military power gives it the capacity to intervene in the region, but not the assurance of genuine regional leadership that it so craves. For this, the Belt and Road Initiative, often nicknamed OBOR (One Belt, One Road) that is at the heart of Xi Jinping’s regional strategy, has become increasingly important. Essentially, it is a proposition that states that cooperation with China’s aims will be rewarded with generous contributions to infrastructural development. Rather than stressing China’s military capacity to force other actors into doing its will, OBOR provides China with the possibility (not yet realised) of rivalling America’s unmatched ‘soft power’ in the region.

Even before November 2016, there were some signs that China’s OBOR strategy was working. Pakistan has welcomed Chinese investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, one of the more advanced parts of a proposed network that is supposed to create a trade zone that stretches from western Europe to Southeast Asia. President Duterte of the Philippines has combined INSults towards the US (referring to Obama as a ‘son of a whore’) with a growing willingness to accommodate Chinese demands--for instance, soft-pedalling the fact that the Philippines had brought a successful case against China at the Hague Tribunal over rights in the South China Sea.

However, Trump’s election has forced all regional actors to reassess their positions, a situation that may continue for many years to come. During the election campaign, Trump’s most notable statements about the region seemed to suggest a sharp withdrawal of American commitment in Asia. He implied that Japan and South Korea might have to obtain their own nuclear weapons rather than relying on the US security umbrella. His unexpected election seemed to raise a few cautious smiles in Beijing. Hillary Clinton was widely regarded as a ‘hawk’ on China issues, and Chinese policymakers welcomed the idea of a president who seemed to know little and care less about the Asia Pacific.

Shinzo Abe meets Xi Jinping at the G20 summit

Those smiles will have been wiped away in the past few weeks. Donald Trump’s actions since his election with regard to China seem to imply confrontation, not withdrawal. His decision to take a phone call from Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen was portrayed as a commitment to an American ally which has shown a commendable commitment to liberal democracy. Yet, Trump’s follow-on comments implied that he was questioning the long-held ‘One China’ policy not through some commitment to liberalism (which was hardly a key part of his domestic electoral platform), but as leverage for better trade deals. The ‘One China’ policy has been maintained by all US governments since 1979; it is an awkward formula that acknowledges certain commitments to Taiwan while making it clear that only one state is recognised as the official voice of China. It is messy and inconsistent in various ways, but it has also helped to maintain the peace between two potentially hostile powers in the region. Trump’s actions have caused confusion in Beijing, as well as much of Asia. How can Trump’s rhetoric of withdrawal from the region, expressed during the campaign, be reconciled with a sudden and seemingly hawkish take on China? Who, in practice, is making Trump’s China policy? An incident in mid-December over a US information-gathering drone captured by the Chinese seemed to sum up Beijing’s dilemma. The action appeared to be another attempt to assert an increasingly confident Chinese presence in the region. However, Trump reacted fast, and uncompromisingly, referring to it as an ‘unpresidented’ event on Twitter (later changed to ‘unprecedented’). The Chinese reacted in turn, accusing the US of ‘hyping’ the incident and indicating that they would return the drone. It is possible that Beijing is testing the edges of what the new president will tolerate, and finding--to its surprise--that he might be serious about confronting China. If this is true, it adds another level of volatility to an already nervous region.

Beijing--like the rest of the world—is also unsure what the significance might be of Trump’s appointment of a Russia-friendly foreign policy establishment in Washington. Moscow and Beijing get on fine these days, but it is an alliance of convenience, not deep friendship. (It was not until 1989 that the hostile Cold War relationship between the two was finally healed.) If the US and Russia, unprecedentedly, became much warmer towards one another, then Vladimir Putin might turn a blind eye to greater American confrontation toward Beijing’s actions in Asia. This scenario might have seemed unlikely just a few months ago; but unlikely foreign policy scenarios are clearly going to be a feature of 2017 in general.

Chinese construction on the Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea

Yet, in another area, Trump’s actions suggest possibilities for Beijing to exploit. The president-elect has made it clear that he will veto the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free trade deal brokered by the US, and signed off in a series of painful political manoeuvres by allies such as Japan, but which excluded China. If the TPP is dead, this gives a new potency to the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), a rival free trade grouping championed by China. The ironic, but real, possibility is there that China could position itself as a status-quo power promoting greater economic integration in Asia, while the US becomes an actor known for unpredictable about-turns on everything from security to trade.

Trump has not even been inaugurated, yet his choices are already making the weather in Asia. However, it is worth noting another transition of power coming up, in autumn 2017. Xi Jinping will mark the halfway point of his ten years in power, and there will be a major change of personnel at the highest levels of Chinese Communist Party. Xi will want to make sure that his time in office is marked by the firm establishment of Beijing, not Washington, as the powerbroking centre in the politics of Asia. So far, the uncertain direction of the US president-elect’s policy on the region has given Beijing plenty of openings, as well as a wider feeling of uncertainty that, left unchecked, may allow truly cold winds to blow across the Pacific Ocean and the seas connected to it. If America fails to give direction in East Asia, we can be sure that China will not allow the gap to last for long.

(The writer is professor of the History and Politics of Modern China, University of Oxford)

Tags