Railroad(ed) to Death

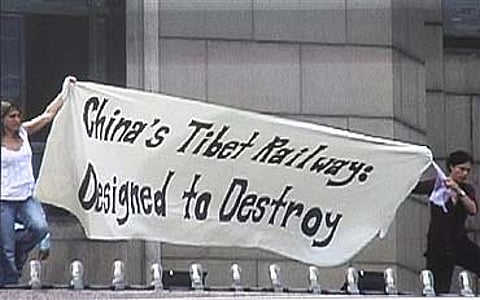

With the inauguration on July 1st by Chinese President Hu Jintao of the New Tibet railway, there is now a railraod from China to Tibet; and one can only hope against hope that the Tibetans will not be railroaded to their extinction.

No one, except perhaps the most devoted advocates of Tibetan independence, will think of comparing this railway line across "the roof of the world" to the notorious "Death Railway" that most people became aware of through David Lean’s film,The Bridge on the River Kwai -- and yet, as shall perhaps become clear, this may be the most apposite comparison at this triumphal moment for the Chinese.

As the Japanese military pushed its way across Southeast Asia and sought entry into India, it commandeered a huge labor force of nearly 275,000 men, comprised largely of conscripted Asian workers and allied POWs, to build a railway line from Bangkok to Burma. Working under the most wretched conditions, nearly 100,000 men succumbed to starvation, malnutrition, fatigue from backbreaking labor, cruel punishment, and diseases such as dysentery, cholera, and malaria. We have a nearly exact tally of the number of British, Australian, Dutch, and American fatalities -- 6,318; 2,815; 2,490; and 131 -- but the Japanese, who are scarcely alone in construing European lives as more worthy than those of miserable Indians, Thais, Koreans, and Burmese, didn’t even bother to count the dead among Asians, some 80,000 of whom are now estimated to have died in less than a year.

The official Chinese news agency has released reports which furnish those tidbits that habitually enthrall people interested in world records, and among edifying facts it emerges that a record 550 kilometers of the tracks run on frozen earth and that, at 5,068 meters above sea level, the Tanggula Railway Station is now the highest railway station in the world. Railway buffs who salivate at the prospect of exciting tunnel rides can, at 4,905 meters above sea level, travel through the world’s most elevated tunnel, the Fenguoshan, on frozen earth, and at 1,668 meters the Kunlun Mountain Tunnel now becomes the world’s longest tunnel on frozen earth.

The newspaper notes that the railway line being laid to Srinagar, which has enjoyed its share of encomiums as a paradise on earth, barely reaches a third of the height scaled by the new train to China. Before the train’s inaugural run, Hu, a trained engineer who also oversaw with his customary efficiency the administration of a martial law regime in Tibet when pro-democracy demonstrations broke out in 1989, described how the world’s highest railway fulfilled a long-cherished dream of the Chinese people and the miraculous enactment of the promise to brings the fruits of socialist modernization to Tibetans and so bring them into the orbit of the civilized world of the global economy.

In all these accounts, and countless other similar ones that will continue to emerge in the near future, the story of the China-Tibet railway is writ large in one word: "development". The argument was put rather more elegantly by the historian William Everdell, who has written that we "call ‘modern’ everything that happened to any other culture after it had built its first railroads." If Hu and the global corps of cheerleaders from the business, media, and political worlds are to be believed, with the arrival of the train into Lhasa from China Tibet itself has finally arrived into history.

Those who speak on behalf of the Tibetans are dismissed as "romantics" or as hypocrites who, while availing themselves of all the comforts and technologies of the modern world, would deny the same privileges to a people held captive to a feudal theocracy. The Chinese are now only prepared to tolerate criticisms that are offered from within the framework of modernity, which explains why, in building the railroad, they have been unusually sensitive to environmental considerations. Official news releases state that the railroad cars have been installed with environmental-friendly toilets, and are equipped with wastewater deposit tanks and garbage disposal facilities. Underpasses have been created to prevent antelopes and other animals from coming on to the tracks. All of this is a piece with the safeguards put into place by the Environmental Protection Bureau, among the most active of state agencies in Tibet. Plastic bags are banned in Lhasa, and the government has shut down industrial units that do not meet environmental guidelines.

The environment is now sacrosanct, but people must remain expendable. Ever so keen to offer Tibet to the world as an illustration of the salubrious effects of the cleansing of feudalism, the Chinese have continued apace with the ethnic cleansing of Tibet. Once a land has been emptied of its people, it must be "repopulated", and among the slightly lesser known consequences of the occupation of Tibet by the Chinese is the immense population transfers that have resulted in the Tibetans becoming a minority in their own country. Han Chinese are now the dominant ethnic group in Tibet, and already by 1996 they outnumbered Tibetans in Lhasa by 2:1.

It is now 46 years since China invaded and occupied Tibet, and the Chinese have come to understand, bolstered in recent years by their growing economic strength, that they can act with utter impunity. The ideologues of development, one might say, have embraced a like view. When the blow must be softened, development’s hardened advocates will speak of development with "human face", "sustainable" development, "shared" development, "alternative" development, but no one will speak of alternatives to development. We have come to the stage where development’s particular contours are hotly disputed, but it is understood that the framework itself must not be abandoned.

Is it really necessary that every part of the world be absorbed into the orbit of the world economy, and is it necessary that every place be judged against some imagined plateau of modern civilization? Will Tibet’s absorption into new tourist circuits be as beneficial to its own people as it will be to tourists? And just what does "beneficial" mean? On whose terms will the Tibetans be brought into the global conversations, perfunctory as they may be, that are presently taking place among those who count themselves as citizens of the world? China and Tibet are now "connected", but what kind of exchanges are likely to take place between the two?

Henry David Thoreau, one might surmise, understood the profound irony of technological blessings: as he wrote in Walden (1854): "We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate." Some conversations and communications cannot take place except under conditions of extreme disparity, and among the most fundamental rights, one that is seldom recognized, is the right of a people to forgo exchanges and conversations that can only render them more vulnerable to dominant worldviews, lifestyles, and cultural norms. There is now a railraod from China to Tibet; and one can only hope against hope that the Tibetans will not be railroaded to their extinction.

Tags