'Welcome To The World Stupid Forum'

As Yasin Malik joked, was the Karachi World Social Forum (March 24-29, 2006) too populated by 'intellectuals'? Or did it at least give a genuine taste of debate, dissent and democratic mobilization to military-ruled Pakistan?

The effigy of theGuantanamo prisoner requires no commentary, perhaps. And yet inthis WSF there is verylittle by way of discussion about or protest against the war inIraq. That which one expectedwould be at the heart of this gathering is left, for the mostpart, unsaid.

Instead of Iraq, dominating the first half of the six-day WSFproceedings is Kashmir.A mournful mug shot of Yasin Malik is plastered all over thewalls of the stadium, grainyblue and white, like an announcement for either a celebrated shaheed or a wanted criminal.His own appearance is in stark contrast to his picture, as hesports, for at least two daysstraight, a bright red shirt and denims, withoccasionally a black-and-whitechecked Palestinian kaffiya thrown over his shoulders. He could be astudent leader at JNU,one of those who stay on in campus politics long after theirtwenties. The real life Yasin is asupbeat as he gets, and with good reason. A plenary session on 26th March – four hours longand four hours late, which means effectively an entire workingday – as well as some off-siteevents around the city, all focus on Kashmir.

Finally, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, dapper as ever, steps up to themic. He speaks inEnglish, and without any trace of the distinctive Kashmiriaccent. The humidity of Karachi’safternoon is quite oppressive, but he keeps his warm cap on, andseems none the worse forhaving waited his turn for several hours. "We have to learnto think,’ he says, ‘out of thebox." A Pakistani journalist I am sitting next to, BadarAlam of The News,rolls his eyesbehind very stylish glasses. "’Wonder who sent that lineto his Inbox," he mutters. The finefeatured,well-dressed, articulate Mirwaiz is far above everyone, Indian,Pakistani andKashmiri alike. No surprise then, that when Yasin finally risesto address the audience inUrdu and English, he almost brings the house down. Kashmirbanega albatta! – "We will createan independent Kashmir yet!" – shout young and not soyoung men, some of them ethnicKashmiris, some just hired help. Middle-class folks sitting onchairs under a billowing redand yellow canopy (shamiana),many of them from south India, Bangladesh, Brazil or Africa,watch peaceably.

Yasin strikes me as preoccupied with his world back in India.Before he takes themic, he is continually in conversation with the writer SoniaJabbar, who appears to be hisclose pal. From the podium he talks of non-violence, and ofRamachandra Gandhi, andArundhati Roy, and Manmohan Singh, and Kamal Mitra Chenoy (aprofessor at JNU whohappens to be sitting in the audience), and of his quarrel withstates, not people. I half expecthim to mention Barkha Dutt as well, but luckily he refrains fromyet more personalreferences connected to his life in Delhi.

He narrates the storyof his political career, whichcomes across, in his version, as rather a romantictransformation from commander (of theJKLF) to prime stakeholder in the peace process, via terriblepassages in unlawful detention.He criticizes the WSF as a mere gathering of"intellectuals", not sensitive to the needs ofthose he calls "stupid people – like myself"."Welcome to the World Stupid Forum," I say toAasim Sajjad Akhtar, a young academic, political activist andcommentator from Lahore whomade a speech the previous day on the same panel as TariqAli, Jamal Juma, and Jeremy Corbyn.

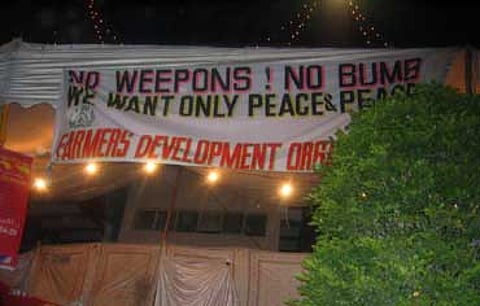

By contrast, a land-based movement in Punjab, represented byAnjuman MazarainPunjab (AMP) or the Tenants Association of Punjab, may have thesupport of somethinglike 10 lakh share-croppers. Pakistan’s ruling militaryestablishment is attempting to turnlong-term hereditary tenants, who have practiced share-cropping(hissa-batai)from generationto generation for the last hundred years, into contract labour (dihadi-dar),and they areresisting, by refusing to pay rent or taxes to the government.On the principle thatpossession (kabza)is nine-tenths of ownership, the protesting farmers don’t sell, don’tvacate, and don’t trade their land or its produce. "Malkiya Maut" – "Ownership orDeath" istheir slogan.

In retaliation, the administration slaps falsecharges on the farmers to get themembroiled in court cases, or detains them under extraordinarynational security and antiterrorismlaws, besides trying to intimidate them with sheer force ofarms. Human andpolitical rights abuses are rampant. Since it already controlsall state institutions, and preventsany democratic processes from unfolding, Musharraf’s regimenow wants to take awaypeople’s material assets, i.e., their lands and homes as well."There are two militarydictatorships in our region,’ says Probir Purkayastha, a WSFIndia organizer, ‘Myanmar, andPakistan." The Burmese may be the worse off of the twocountries, but Pakistanis arebeginning to have enough as well.

Aasim Sajjad Akhtar, who teaches colonial history at the LahoreUniversity ofManagement Sciences (LUMS), an expensive private college,introduces me to Liaqat Ali andMehr Abdul Sattar, the leaders of the AMP, which they translatefor me as "Organization ofLandless Peasants". Aasim is a wiry, youthful, and Idaresay somewhat intense radicalassociated with this movement. Educated in England and America,he coordinates, togetherwith Asha Amirali, another prominent left ideologue, theIslamabad-based Peoples RightsMovement (PRM). The man speaks good Urdu, but writes about theAMP mainly in Englishlanguage newspapers and journals. He could belong to anothertime, a time that has passedinto history for the organized left in India.

Talking to Aasim,and to the older, more rusticand more wily Punjabi farmers Ali and Sattar, I get the sensethat Pakistan’s long-overduedate with land reform is now coming back to haunt it. Troublehas been brewing in Okaradistrict since 2000. While the peasant uprising Aasim secretlyhopes for and perhaps talks tohis LUMS students about may not occur in a dramatic fashion anytime soon, it’s clear thatthe struggle between tenant cultivators and the military hasalready reached a high pitch,occasioning some violence, mass jailings, injuries and even theloss of a handful of lives.

Marxist ideas, Gandhian methods (though perhaps in some othername), the legacyof anti-colonial struggle, examples of people’s struggles inthe regional neighbourhood (likethe Narmada Bachao Andolan in India), revolutionary (inquilabi)rhetoric and progressivethinking in intellectual circles involved with new socialmovements in Pakistan, have boostedAMP’s agitation. It is muted by Indian standards, butnevertheless shows signs of growing toattain the kind of critical mass necessary for political change.In an essay in the NewInternationalist (No. 349),titled "The Democracy Killers", at the time of the presidentialreferendum in 2002, Aasim wrote:

There are not many in Pakistan willing to support the AnjumanMazarain Punjab (Tenants Associationof Punjab).

Almost a million landless tenants in 10 districtsacross the most populous and richestprovince in the country have come together to demand rights toland they have tilled for a century.Their struggle directly confronts the military authorities thatoperate these farms. The struggle shouldstrike at the moral conscience of this society because itilluminates the amazing resilience andresistance of those who have been oppressed for generations –and the kind of vision that thiscountry should be built on. Scores of tenant farmers have beenkilled, imprisoned and harassed.

In the intervening 3-4 years, however, the AMP and the PRM haveboth matured asrural and urban expressions, respectively, of the long repressedand frequently interruptedsearch for democratic politics in Pakistan. Arguably hosting theWSF, too, is such anexpression. Aasim disagrees, as he finds the WSF in Karachi,dominated by NGOs and themedia, not political enough for his liking. But against hiscriticisms, it has to be said that twoissues which were central in the WSF agenda this year, namely,the rights situation inBalochistan and water problems in Sindh, both did lend anovertly political temper to theproceedings, at least from the point of view of its domesticparticipants and audience.Strident anti-government rhetoric from the Balochis and fromSindhi fisher-folk, and criticalreflections from prominent politicians like Javed Jabbar andIqbal Haider, did suggest thatthe Sports Complex on Kashmir Road may have acted, ifmomentarily, as something of acounter-weight to General Musharraf’s presence in Karachiduring the latter part of the WSF.

But even if the WSF isn’t a harbinger ofdemocracy, it’s good for Karachi’ssagging morale to play host to a third of this"polycentric" global event, split this year over Bamako (Mali), Caracas (Venezuela) and Karachi (Pakistan). Thebuzz among the event’sorganizers was that as many as 40,000 people attended, from 58countries. A beautiful,cosmopolitan and over-populated city, so much like its sisteracross the water, Mumbai, inrecent years Karachi has suffered miserably for being theheadquarters of communalmobilizations, terror networks, underworld activity, big andpetty crime, jihadi groups,and tome always one of the most heinous events since 9/11, thekidnapping and murder ofAmerican journalist Daniel Pearl. Citizens can’t believe thatall kinds of foreigners, especiallythe ever-hostile Indians, would risk coming to their city insuch large numbers, for anyreason other than cricket. People have come, though, evensceptics like me. Danny Pearl wasmy friend and I find it hard to forgive his gory death, butKarachi turns out to be a pleasantsurprise.

WSF 2006 may not even remotely begin to bring down Musharraf,but at least itgives Pakistanis a taste of the debate, dissent and democraticmobilization that they so sorelymiss in their own society.

Ananya Vajpeyi is a Fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum andLibrary, NewDelhi.

Tags