This is the cover story for Outlook's 11 September 2024 magazine issue 'Lest We Forget'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

A Collective Agony That Handwara Refuses To Forget

Muhammad Iqbal Shah’s 14-year-old cousin was gang-raped and murdered at Handwara town, Kupwara, in 2007. The family is still trudging along the long road to justice

The trudge to the desolate apple orchard wasn’t easy for Muhammad Iqbal Shah. After 17 years of awaiting justice, Muhammad was returning to the crime scene in the Batapora highlands of Handwara, around 100 km north of Srinagar, where his 14-year-old cousin was stripped and gang-raped by four men in 2007, who then slit her throat and left her to die.

Along the trek, Muhammad, a physics teacher in a government school, struggles to maintain his composure. His voice breaks and tears stream down his face as he points to the exact spot where her bag was later found all those years ago. He is even more overwhelmed when he reaches the exact spot, where her remains were found 17 years ago, clumsily hidden under grass heaps.

The long road to justice for Muhammad and the Shah clan has several judicial pit stops. He is currently at the second one.

The four accused persons, Sadiq Mir, Azhar Mir, Jahangir Bihari and Suresh Mochi, were sentenced to death by the Sessions Court in 2015, which classified the crime as one that fits the “rarest of rare” billing. The killers have since appealed to the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir, seeking remission of the death penalty.

J&K’s additional advocate general, Mubeen Wani, told Outlook that the case dragged on before the High Court’s divisional bench due to the Covid pandemic, but is now reserved for judgement after daily hearings. “For the past month, the Court has been hearing the case on a daily basis and we expect the Sessions Court’s judgement to be upheld,” he said, emphasising the need for the death penalty in light of recent tragedies, including the recent rape and murder case in a leading hospital in Kolkata.

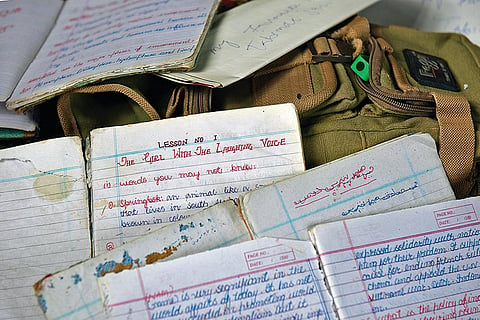

In his two-storey home at Batapora, Muhammad, along with his uncle and the victim’s father Abdul Gani Shah, lay out newspapers, court judgements and personal mementos of the deceased victim, including her school bag and books. Muhammad’s son sits alongside. Their collective agony is evident.

“We live with it every day and have instructed our younger generations to endure it as well. We can’t forget,” says Muhammad.

On July 20, 2007, the police were informed that a schoolgirl was raped and murdered in an orchard at Batapora Wuder. They found the body hidden under grass and earth, with her throat slit. Four suspects were identified and a First Information Report (FIR) was filed under Sections 302, 376 and 34 of the Ranbir Penal Code (RPC). Apart from detailing her injuries, including the fatal neck wound, the postmortem also traced sawdust on her face, nostrils and mouth. A short distance away, investigators found her school bag, hair clip and school shoes. They also found glass tumblers and one wine bottle nearby. The postmortem confirmed gang rape.

The incident sparked widespread protests and public outrage at both local and state levels. During questioning, Sadiq Mir revealed that he, along with Azhar Mir, Jahangir Bihari and Suresh Mochi, had waylaid and dragged the minor schoolgirl from the road through cornfields. The prosecution revealed that Jahangir gagged the victim before all four accused gang-raped her. Fearing exposure, they conspired to kill her, with Jahangir slitting her throat using Sadiq Mir’s knife. They then hid the body under earth and grass. Medical examination showed scratches on the accused, indicating the victim’s struggle. The crime was premeditated, as the group had planned to find a girl to rape and kill during a low-traffic day in the Batapora Wuder area, according to the prosecution.

The defence argued that the case relied on circumstantial evidence and didn’t qualify as a “rarest of rare” case warranting the death penalty. They sought leniency due to the young age of the three accused and Suresh’s family responsibilities.

On April 24, 2015, the Principal Sessions Judge in Kupwara likened the gang rape and murder to the Nirbhaya case, emphasising the gravity of such crimes. He noted that leniency would send a negative message, stating that the convicts acted like “beasts” and their actions fell within the “rarest of rare” category. The judge dismissed the defence’s argument for life imprisonment, concluding that the crime warranted the death penalty under Section 302/34 RPC, as no alternative was justifiable given the heinous nature of the offence.

While the wheels of justice continue to turn over the years, the topography around the crime scene changed since the horrific crime. There is now a new one-storey house adjacent to the road in the apple orchard, that lay deserted when Outlook accompanied Muhammad to the scene of the crime.

The village where the victim was raised has changed too. While roads have been macadamised, the scars of the gang rape and murder have altered social behaviour, especially when it comes to children. Now, girls in uniform travel in groups to and from school. After the incident, separatists labelled the crime a “collective assault on Kashmiris”, as it involved both locals and non-locals, even as then Chief Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad called for a swift investigation. In June 2008, the state government also instituted a Bravery Award in remembrance of the victim, but it was given only once and has since been forgotten.

An elderly villager recalls that the day of the incident is still remembered as the darkest in the village’s history. When the police handed over the victim’s mortal remains, the family, in fear, hid it in Muhammad Shah’s house instead. “We closed the windows. We closed the doors. We were so fearful. We thought her body could be snatched from us,” says Muhammad, wiping tears from his eyes.

When the victim’s aunt retrieves the deceased seventh-grade girl’s school bag and books, Abdul Shah lovingly runs his fingers over her neat, precise handwriting. Inside the bag, he finds a sharpener. From the corridor, quiet sobs among the women turn into loud cries. “Her memories have not faded,” says Muhammad. “One day we will meet her.”

The family has carefully preserved newspaper clippings related to the tragedy over the years. Abdul Shah spreads out these papers, which include both prominent and obscure local publications. “For nearly 40 days, (she) was on the front pages of all local newspapers,” he notes. At the time, leaders from various political backgrounds visited the family to offer their condolences. As Abdul stares at his daughter’s picture in a newspaper clipping, the family insists that they still haven’t found closure, despite the Sessions Court judgement and testimony from around 85 witnesses. “We are still struggling for justice,” says Abdul. “My two brothers passed away in the course of the (court) hearings,” he adds. On the fatal day, the grieving father recalls, the family was expecting the girl to join them for a meal. Instead, they received her bruised body.

On June 21, 2007, there was no space in the village for a daughter’s burial. Despite restrictions imposed by the authorities, thousands of people flocked to the area. Her last rites were eventually held in the village of Langate, the home of incarcerated MP Engineer Rashid. “Had they implemented the judgement of the Sessions Court in this case, we would not have seen (other rape cases follow),” says Muhammad. “It would have proven to be a great deterrent.”

“We are not asking anything new. We are demanding justice. We want the judgement given by the Court to be implemented in its letter and spirit,” says Abdul, even as Muhammad points to the victim’s handwriting. “She was particular about her handwriting. Isn’t it beautifully written?” he asks, pointing at a specimen of her handwriting in a book. The passage reads: “Lesson number 1, the girl with language, voice.” Scrawled below it is the line: “Words you may not know.”

(This appeared in the print as 'Here, Nobody Speaks of the Wounds')