An Alternative Proposal

How does one meet the challenge of Mandal II? Is there a way forward where both merit and social justice can be given their due?

This is clearly an ambitious and optimistic agenda, especially because MandalII proves that some mistakes are destined to be repeated. Once again the governmentappears set to do the right thing in the wrong way, without the priorpreparation, careful study, and opinion priming that such an important moveobviously demands. It is even more shocking that students from our very bestinstitutions are willing to re-enact the horribly inappropriate forms of protestfrom the original anti-Mandal agitation of 1990-91. As symbolic acts,street-sweeping or shoe-shining send the callous and arrogant message that somepeople — castes? — are indeed fit only for menial jobs, while others are`naturally' suited to respectable professions such as engineering and medicine.However, the media do seem to have learnt something from their dishonourablerole in Mandal I. By and large, both the print and electronic media have notbeen incendiary in their coverage, and some have even presented alternativeviews. Nevertheless, far too much remains unchanged across 16 years.

Perhaps the most crucial constant is the absence of a favourable climate ofopinion. Outside the robust contestations of politics proper, our public lifecontinues to be disproportionately dominated by the upper castes. It istherefore unsurprising, but still a matter of concern, that the dominant viewdenies the very validity of affirmative action. Indeed the antipathy towardsreservations may have grown in recent years. The main problem is that thedominant view sees quotas and the like as benefits being handed out toparticular caste groups. This leads logically to the conclusion thatpower-hungry politicians and vote bank politics are the root causes of thisproblem. But to think thus is to put the cart before the horse.

Table 1 shows the percentage of graduates in the population aged 20 years orabove in different castes and communities in rural and urban India. Only alittle more than 1 per cent of Scheduled Tribes, Scheduled Castes, and Muslimsare graduates in rural India, while the figure for Hindu upper castes is four tofive times higher at over 5 per cent. The real inequalities are in urban India,where the SCs in particular, but also Muslims, OBCs, and STs are way behind theforward communities and castes with a quarter or more of their population beinggraduates. Another way of looking at it is that STs, SCs, Muslims, and OBCs arealways below the national average while the other communities and especiallyHindu upper castes are well above this average in both rural and urban India.

Numbers below 100 indicate under-representation, above 100 indicate over-representation - showing that STs, SCs, Muslims and other OBCs are severely under-represented. Sikhs, Christians, Hindu upper-castes and others are over-represented.

Table 2 shows the share of different castes and communities in the nationalpool of graduates as compared to their share of the total population aged 20years or more. In other words, the table tells us which groups have a higherthan proportionate (or lower than proportionate) share of graduates. Once again,with the exception of rural Hindu OBCs and urban STs, the same groups areseverely under-represented while the Hindu upper castes, Other Religions (Jains,Parsis, Buddhists, etc.), and Christians are significantly over-representedamong graduates. Thus the Hindu upper castes' share of graduates is twice theirshare in the population aged 20 or above in rural India, and one-and-a-halftimes their share in the population aged 20 or above in urban India. Comparethis, for example, to urban SCs and Muslims, whose share of graduates is only 30per cent and 39 per cent respectively of their share in the 20 and abovepopulation.

It should be emphasised that these data refer to all graduates from all kindsof institutions countrywide — if we were to look at the elite professionalinstitutions, the relative dominance of the upper castes and forward communitiesis likely to be much stronger, although such institutions refuse to publish thedata that could prove or disprove such claims.

Although it is implicitly conceded by both sides, upper caste dominance isexplained in opposite ways. The upper castes claim that their preponderance isdue solely to their superior merit, and that there is nothing to be done aboutthis situation since merit should indeed be the sole criterion in determiningaccess to higher education. In fact, they may go further to assert that anyattempt to change the status quo can only result in "the murder ofmerit." Those who are for affirmative action argue that the traditionalroute to caste dominance — namely, an upper caste monopoly over highereducation — still remains effective despite the apparent abolition of caste.From this perspective, the status quo is an unjust one requiring stateintervention on behalf of disadvantaged sections who are unable to force entryunder the current rules of the game. More extreme views of this kind may go onto assert that merit is merely an upper caste conjuring trick designed to keepout the lower castes.

It is their confidence in having monopolised the educational system and itsprerequisites that sustains the upper caste demand to consider only merit andnot caste. If educational opportunities were truly equalised, the upper castes'share in professional education would be roughly in proportion to theirpopulation share, that is, between one fourth and one third. This would not onlybe roughly one third of their present strength in higher education; it wouldalso be much less than the 50 per cent share they are assured of even afterimplementation of OBC reservations!

If the upper caste view needs an unexamined notion of merit that ignores thesocial mechanisms that bring it into existence, the lower caste orpro-reservation view appears to require that merit be emptied of all itscontent. While this is indeed true of some militant positions, the peculiarcircumstances of Indian higher education also allow alternative interpretations.In a situation marked by absurd levels of "hyper-selectivity" —300,000 aspirants competing for 4000 IIT seats, for example — merit getsreduced to rank in an examination. As educationists know only too well, theexamination is a blunt instrument. It is good only for making broad distinctionsin levels of ability; it cannot tell us whether a person scoring 85 per centwould definitely make a better engineer or doctor than somebody scoring 80 percent or 75 per cent or even 70 per cent.

In short, it is only a combination of social compulsion and pure myth thatsustains the crazy world of cut-off points and second decimal place differencesthat dominate the admission season. Such fetishised notions of merit havenothing to do with any genuine differences in ability. The caste composition ofhigher education could well be changed without any sacrifice of merit simply byinstituting a lottery among all candidates of broadly similar levels of ability— say, the top 15 or 25 per cent of a large applicant pool.

But the inequities of our educational system are so deeply entrenched thatcaste inequalities might persist despite some change. We would then be backwhere we started — with the apparent dichotomy between merit and socialjustice in higher education. How do we transcend this dilemma? Is there a wayforward where both merit and social justice can be given their due?

Let us present the basic principles that underlie this proposal beforegetting into operational details. First of all, this proposal is based on a firmcommitment to policies of affirmative action flowing both from theconstitutional obligation to realise social justice and also from the overallsuccess of the experience of reservations in the last 50 years. Secondly, werecognise the moral imperative to extend affirmative action to educationalopportunities, for a lack of these opportunities results in theinter-generational reproduction of inequalities and severely restricts thepositive effects of job reservations. Thirdly, it needs to be remembered thatthe end of affirmative action can be served by various means includingreservation. The state's basic commitment is to the end, not any particularmeans. Finally, flowing from the experience of reservations for socially andeducationally backward classes (SEBCs), we need to recognise that there aremultiple, cross-cutting, and overlapping sources of inequality of educationalopportunities, all of which need redress. This is what our proposal seeks to do.

The proposal involves computing scores for `academic merit' and for `socialdisadvantage' and then combining the two for admission to higher educationalinstitutions. Since the academic evaluation is less controversial, weconcentrate here on the evaluation of comparative social disadvantage. Wesuggest that the social disadvantage score should be divided into its group andindividual components. For the group component, we consider disadvantages basedon caste and community, gender, and region. These scores must not be decidedarbitrarily or merely on the basis of impressions. We suggest that thesedisadvantages should be calibrated on the basis of available statistics onrepresentation in higher education of different castes/communities and regions,each of these being considered separately for males and females. The requireddata could come from the National Sample Survey or other available sources. Itwould be best, of course, if a special national survey were commissioned forthis purpose.

Besides group disadvantages, this scheme also takes individual disadvantagesinto consideration. While a large number of factors determine individualdisadvantages (family history, generational depth of literacy, siblingeducation, economic resources, etc.), we believe there are two robust indicatorsof individual disadvantage that can be operationally used in the system ofadmission to public institutions: parental occupation and the type of schoolwhere a person passed the high school examination. These two variables allow usto capture the effect of most of the individual disadvantages, including thefamily's educational history and economic circumstances.

In the accompanying tables, we illustrate how this scheme could beoperationalised. It needs to be underlined that the weightages proposed here aretentative, based on our limited information, and meant only to illustrate thescheme. The exact weights could be decided after examining more evidence. Wesuggest that weightage for academic merit and social disadvantage be distributedin the ratio of 80:20. The academic score could be converted to a standardisedscore on a scale of 0-80, while the social disadvantage score would range from 0to a maximum of 20.

Table A shows how the group disadvantage points can be awarded. There arethree axes of group disadvantage considered here: the relative backwardness ofthe region one comes from; one's caste and community (only non-SC-ST groups areconsidered here); and one's gender. The zones in the top row refer to aclassification of regions — this can be at State or even sub-State regionlevel — based on indicators of backwardness that are commonly used and can beagreed upon. Thus Zone I is the most backward region while Zone IV is the mostdeveloped region. The disadvantage points would thus decrease from left to rightfor each caste group and gender.

The castes and communities identified here are clubbed according to broadlysimilar levels of poverty and education indicators (once again the details ofthis can be agreed upon). The lower OBCs and Most Backward Castes along with OBCMuslims are considered most disadvantaged or least-represented among theeducated, affluent, etc., while upper caste Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains,Parsis, etc., are considered to be the most `forward' communities.

Disadvantage points thus decrease from top to bottom. Gender is built intothis matrix, with women being given disadvantage points depending on their otherattributes, that is, caste and region. Thus the hypothetical numbers in thistable indicate different degrees of relative disadvantage based on all threecriteria, and most importantly, also on the interaction effects among the three.Thus, a woman from the most backward region who belongs to the lower OBC, MBC,or Muslim OBC groups gets the maximum score of 12, while a male from the forwardcommunities from the most developed region gets no disadvantage points at all.

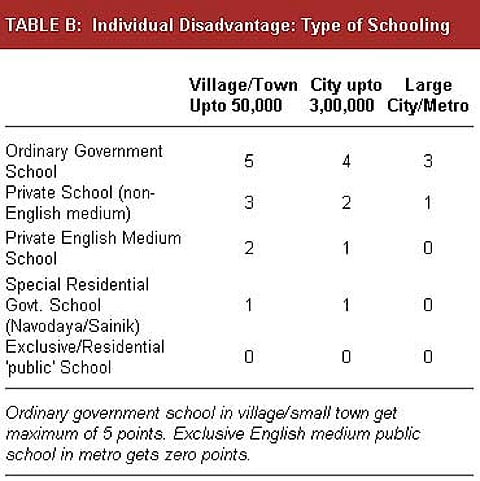

Tables B and C work in a similar manner for determining individualdisadvantage. For these tables, all group variables are excluded. Table B looksat the type of school the person passed his or her secondary examination from,and the size of the village, town, or city where this school was located. Anyonegoing to an ordinary government school in a village or small town gets themaximum of 5 points in this matrix. The gradation of schools is done accordingto observed quality of education and implied family resources, and this couldalso be refined. A student from an exclusive English medium public school in alarge metro gets no disadvantage points.

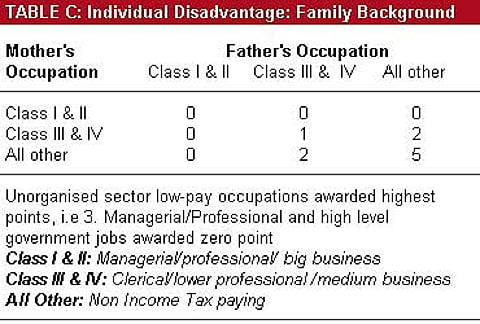

Table C looks at parental occupation as a proxy for family resources (thatis, income wealth, etc., which are notoriously difficult to ascertain directly).Since this variable is vulnerable to falsification and would need some effortsat verification, we have limited the maximum points awarded here to three.Children of parents who are outside the organised sector and are below thetaxable level of income get the maximum points, and the occupation of bothparents is considered. Those with either parent in Class I or II jobs of the government, or in managerial or professional jobs get no points at all.Intermediate jobs in the organised sector, including Class III and IV jobs inthe government, are reckoned to be better placed than those in the unorganised,low pay sector.

Combining the scores in the three matrices will give the total disadvantagescore, which can then be added to the standardised academic merit score to giveeach candidate's final score. Admissions for all non-SC-ST candidates, that is,for 77.5 per cent of all seats, can then be based on this total score.

While our proposal shares with the proposal mooted by the Ministry of HumanResource Development (MHRD) the commitment to affirmative action and the desireto extend it to educational opportunities, the scheme we propose differs fromthe Ministry's proposal in many ways. The Ministry's proposal seeks to create abloc of `reserved' seats. Our proposal applies to all the seats not covered bythe existing reservation for the SC, ST, and other categories. The MHRD proposalrecognises only group disadvantages and uses caste as the sole criterion ofgroup disadvantage in educational inequalities. We too acknowledge thesignificance of group disadvantages and that of caste as the single mostimportant predictor of educational inequalities. But our scheme seeks tofine-tune the identification by recognising other group disadvantages such asregion and gender. Moreover, our scheme is also able to address the interactioneffects between different axes of disadvantage (such as region, caste, andgender, or type of school and type of location, etc.).

While recognising group disadvantages, our scheme provides some weightage toindividual disadvantages relating to family background and type of schooling.Our scheme also recognises that people of all castes may suffer from individualdisadvantages, and offers redress for such disadvantages to the upper castes aswell.

Tags