First, a real incident, with a Rashomon-like many-sidedness. This is one side, the male side, as retold by a professor at a university in Delhi in the centre of it. Not known to hold back his words, he recently asked a woman student not to smoke marijuana—or make out, depending on the version—on campus. The conversation was clumsy from the word go, he admits. He was admonitory in his tone, she got up on her feet and danced a little mocking jig then and there. He said he would not hesitate to slap her. Then, in turn, the student threatened to slap him...with charges of sexual harassment.

Battle Of The Sexes

While Fortress Patriarchy remains unbreached and rapes, trafficking, molestation and the khap mindset prevail, urban India is bracing for a backlash. The naming and shaming of male co-workers and teachers on social media has become a substitute for the due process of law.

Nothing got out. (Not even the girl’s version.) A call to “her dad” smoothed out things, but he’s left with an unsettled feeling. “There exists here the difference between story and myth—one is scientific, factual, verifiable. The other is imaginary.”

Not all imaginary, of course. To witness long columns of young women and men march into the streets against gender-based harassment is to watch a thousand flowers bloom, so to speak, at picket lines in universities across India—a JNU here, a Banaras Hindu University there—or to watch committees keep vigil over hard-won mixed-gender office spaces. Even to encounter online the ‘informal’ testimonies of women speaking out against the abuse they have faced…all this can be terrifying and comforting at the same time. Even lathicharges and skunk-water cannons have not dampened the clarion call against sexual abuse, by all accounts a rampant phenomenon in Indian institutions. It’s valuable: the injection into the public space of accounts by women of the vexing circumstances they face forces everybody to bear witness to the other, disempowering, side of women at the workplace. Still, after a series of incidents that ravaged reputations on social media, it’s evident that all this comes wrapped in doubt, introspection, even fear.

It’s a terrible paradox. Perhaps the most empowering sign of the 20th century’s socio-economic gains—women joining the formal workforce on an equal footing—has given rise to the troubling phenomenon of workplace harassment. Male entitlement is a reality, as is an almost structural kind of female victimhood. But as modern India navigates the risky terrain of debate, one aspect has perhaps gone unaddressed. A kind of inversion of a basic legal principle seems to operate whenever allegations of sexual harassment are made—instead of innocence, it’s guilt that is presumed. It’s not just that there is a rush to judgement: as the Indian chapter of #MeToo and a spate of other cases showed, accusation and judgement collapse into one. The whole process of arriving at a judgement shrinks to naught. The accused stands automatically damned.

The ambiguous territory of sexuality—where both sides can be complicit in a sense—tends to get denied here. So does the possibility of false allegations. No wonder then the male gaze is justifiably dissolving into fear. Can women “use” the law? Only the most essentialised scrutiny will deny this happens. The nature of the crime—it’s not always the case that a paper trail or electronic footprint is available to judge the crime by—is such that often there is only the accusing woman’s testimony to go by. This lies at the core of doubts and anxieties amidst the polarisation between genders unfolding in universities, courtrooms and offices. One consequence is a kind of institutional blowback, where the very difficult gains made by the feminist movement are themselves at some risk of being forfeited.

Witness the Supreme Court opining on the dangers inherent in asking for the automatic arrest of husbands and in-laws in dowry cases. Or high courts that find much is wrong when a young woman extends a “long hug” to a male friend. The fodder also arrives in the form of women who approach the courts—though they are legally entitled to do this—alleging rape when the man seduced her, or when she engaged in consensual sex only because the man had promised marriage. The courts are all too often finding it hard to digest such instances as a form of ‘rape’—the Gujarat High Court reiterated the doubt this week.

Yes, the law does not operate the way it should—the conviction rate for rape is just 24 per cent. But there isn’t yet an acknowledgement of the fact that a man named as an offender in any sexual crime is also destroyed in a certain way. It’s almost as if it were a sort of psychological judo, a sport in which a tiny person (the woman) can overturn the bigger person. The effect of this: a kind of rampant male self-doubt. This also becomes a warning to those who tread a fuzzy line, who deliberately cultivate ambiguity in word or deed. Male-female polarisation exists even in the west, so it’s not just an Indian phenomenon.

“Women will ‘use’ the law as it’s their only route to revenge, hence we see cases of abandonment of partners emerge as rape trials. It’s the woman, the weaker one, getting even,” says Deepak Mehta, head, department of sociology at Shiv Nadar University. And yet the police, a state institution, also ‘uses’ the law—in cases of elopement, for instance, especially those involving minors, the police routinely use the law of abduction “in a peculiarly perverse way”.

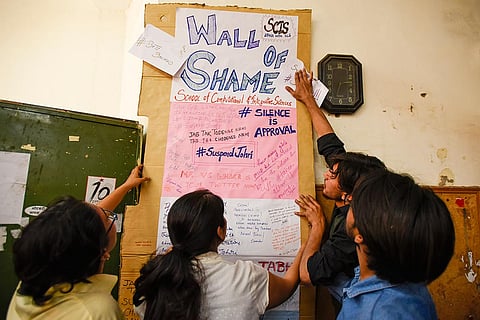

As students enforced a lockdown in JNU against the administration’s policies, several ‘student notices’ like this one came up at many places on campus

How, then, should civil society, which wants laws but no witch-hunt, strategise for attaining gender justice? The khap panchayats address the issue in one way. MeToo perhaps hews closer to the other extreme. A list of ‘offenders’ that made no distinction between the different items that feature on it. “If it is a list of powerful men, then it itself usurps power, leaving no room for debate,” says Mehta. He is absolutely clear that he does not condone the behaviour of sexual offenders, merely pointing out that such a list eventually relies on the integrity of the lister, inviting unsavoury explanations for why it was drawn up.

Poet-anthologist Sudeep Sen was recently accused by a younger female poet of harassment—unwanted proposals and ignored rejections, which Sen vehemently denies. “The charges reek of falsehood, mala fide intent and are a complete fabrication of her imagination. They have no basis or proof. I feel very wronged and deeply hurt by them. No formal complaint has been filed—it was just a wild rant on Facebook, and people joined in, acting as judge and jury in a kangaroo court, with their knee-jerk instant response and condemnation,” he says. Since the accusation surfaced, the poet community has been split. One side withdrew from the anthology he was working on. The other, he informs, has been sending him gifts and flowers. “Many people are saying her allegations have to do with her achieving no status as a poet, remaining obscure in this field,” he says. (See box for the woman’s response)

The other fear is that the laws related to sexual harassment, dowry and domestic violence, for example, are making relationships between men and women fraught at work and within the family. All of last week, the case of a Karnataka first-class magistrate and her male superior was in the headlines—she had accused him of sexual harassment; a “false” complaint, says one side, filed only after he had reported her for misconduct. The whole thing has got caught up in the high-profile fight between the Centre and the Supreme Court collegium. The male judge was cleared in a probe once, but the Union law ministry raked it up again—the woman judge, meanwhile, told Outlook: “I have not got justice.” Another test-case filled with indeterminacy.

Males now testify to a fear of proximity with females in formal spaces, even of hiring women. The concern reached its crescendo after the MeToo list last October. “This so-called fear,” says Vrinda Grover, senior advocate, Supreme Court, “predates MeToo.” While acknowledging misuse of law, she would rather put the focus on the “documented underuse” of law. In her mind, it’s an institutional “backlash” to women actually pushing for their rights. “The list only flagged that due process has to work harder to increase women’s access to legal recourse. The fear among men was certainly not created by it.”

Grover was recently approached by students and professors from JNU who had been protesting against Atul Johri, a professor charged with sexual harassment by at least eight students and researchers. “When internal mechanisms failed,the students went to the police. But Johri was granted bail within an hour,” she says. The details are significant as the law distinguishes between the level of truth required from a complainant in a case being examined by an institution’s internal complaints committee (ICC) versus a criminal case filed with the police. The first, a civil matter, sets a lower bar, and relies in a sense on probability. In criminal complaints, the requirement is of truth “beyond reasonable doubt”. Also, the ICC cannot reveal names of either parties to the disputed occurrences. Criminal cases, being a matter of public record, give no such protection to the accused.

“If Johri sought protection of his identity, he should have submitted to the ICC,” Grover says. What she means is, in such cases, women are seen by the law to have much more at stake than the men they accuse and to argue against this is to withdraw legal protections from women altogether. “Our Constitution overlays rights for women and Dalits over a feudal country unaccustomed to seeing them or the poor as rights-bearers. That is why we can think they ‘misuse’ the law,” she says. Her prognosis is not encouraging: “If today there is a referendum on the Constitution we would not be able to keep it. It would be rejected.”

Lawyers and activists see the crisis-level attention on gender laws as a sign of being on the cusp of change. It’s not the “chaos” of protests or the heavy-handed police response that worries them. The concern, which often surfaces as a dispute within feminist-lawyer circles, is that “tragedy should not get routinised”, in the words of Supreme Court advocate Rebecca John.

She is referring to both the Aarushi murder case and MeToo. Acquittal for the Talwars, after years of incarceration, was a big reversal whereas their earlier conviction was all but foretold in the scandalous media coverage of the Aarushi case. On MeToo, feminists had to negotiate the tricky question of whether ‘The List’ undermined criminal jurisprudence. “It was easy for India to come together for a case like Nirbhaya, it was so brutal, there were no shades of grey. But in an array of other cases, there can’t but be complicated, problematic facts and our response to them depends on which side we’re on,” says John. Right now, she says, a complex phase is under way, where politics too has a role. “As a criminal lawyer I cannot undermine due process. Guilt is pronounced by courts, not announced in lists. That doesn’t mean I don’t understand how due process has let women down.”

The problem begins with how any naming inherently carries an element of shaming. Also, how to define what offence has taken place and how to moderate responses from women accordingly. “There is sexism, there is sexual harassment, there is moral policing. Not everything is sexual harassment and yet a lot that happens is. One side doesn’t have patience, the other side lacks understanding. We’ve sadly come to a stage where you can’t put across a sane point. Even the worst criminal deserves a trial,” says John.

Around 20 women students in Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University (RMLNLU), Lucknow, have been grappling with these questions since last year. They have accused two senior members of the administration with sexual harassment and moral policing. Says an angry complainant, “One of the accused would check out girls, especially their breasts, making them uncomfortable. They tell us it amounts to sexual harassment only if sexual favours are demanded. So what was it when girls were threatened that their parents will be told that they have boyfriends? Not harassment? Plus, lewd comments were made and twenty students complained, not a small number—was this sexism, moral policing or harassment?”

One RMLNLU professor insists the answer cannot be divined externally—simply because the internal complaints committee has not shared its final report with the complainants or the accused, as required by law, though the deliberations were over months ago. Another professor says there will always be differences in perceptions and definitions—the two sides are not just males and females, but are tied in formal ways, and, RMLNLU being a residential campus, spend a lot of time together. “If a boy and girl hold hands or walk around at night that’s no offence even if some in the administration have a problem with it. Moral perceptions vary, it can’t become an excuse to curtail young people’s liberties,” he says.

“Three of the women made motivated complaints against me and I want to take action against them. I never asked for sexual favours. I want to get the police intelligence reports of their protests last year and nail them for conspiracy,” says one of the accused, who says he has “found out from sources” that the ICC has absolved him. A complainant responds: “The law has not restricted sexual harassment to touch. But now my parents want me to lie low since he is threatening with lawsuits.” His behaviour, the students say, remains unchanged.

“In university after university I find similar problems, of administrations blocking due process in different ways,” says senior advocate Flavia Agnes. Academic institutions often don’t even publicise a code of behavior, she says “They should be conducive to healthy behaviour and the law gives broad guidelines on how to do this. Beyond this, institutions are supposed to find their own way but this almost never happens.”

Some answers are coming from the very places where the anxieties radiate from—the classrooms. Madhavi Menon, an English professor at Ashoka University, asks her class to consider several possible responses and talk about structural change instead of quid pro quo. “Sexual harassment generates powerlessness and our response is not always that you, the male, are the aggressor and I, the female, a victim, but that I, the woman, have to be strong enough to say no,” she says. Menon emphatically adds that the cumulative effect of male behaviour—which is often bad—generates the narrative of weak women and predatory men. “India has a shocking history of not listening to women, which has led to the conflicts playing out today,” Menon says. Take the phenomenon of women complaining about sexual crimes years after they took place. “It is sad so many could not speak out for years,” says Menon. “They are speaking out now because instead of being told to say ‘I was too weak’ or ‘no’ we are taught to shut up and say nothing.”

Students of JNU protest against impunity for sexual harassment and moral policing by administrators

The arc extends from saying nothing to an excess of speech. An online troll’s crude expressions of sexual assault and fantasy, for instance, are a kind of scripted emotional experience played out before the public, generating even more disorder. What about the offline world? With a boss, colleague or associate, people forget that what they may share is not ‘love’ but proximity. Desire, it can be argued, always forces men and women to get familiar with what is not-so-good within them. New rules, fresh taboos are needed to cope with the changing legal and social landscape; anything else amounts to playing a dicey game. This is why, while inappropriate touch always existed, its acceptability has changed. “To speak against it is now seen as courageous, empowering and worthy of validation,” says Mumbai-based psychiatrist Harish Shetty. “Women who ‘use’ their femininity still exist, as do awakened women. Between them, the zone of harassment is not black or white but includes a whole lot of consent, explicit and implied,” he says. Whether ICC meetings or a psychologist’s couch are better equipped to handle every nuance and ambiguity between men and women is a question he raises.

Gender conflicts in the workplace arise from mundane activities: travelling or drinking together etc. Shetty advises caution on each front as a response to how today’s laws regard these areas of long cohabitation with potential for conflict. “Emotional and physical closeness generate relationships at work but when things collapse—often when the man finds another emotional interest—the woman may feel used. This can result in a complaint to HR,” he says. “At the same time, men are predators—big predators.”

He has encountered consent, force, part-consent, part-force, and shades in-between among those who come to his clinic. To men, he advises short, not long, one-on-one meetings with female colleagues, especially if the man is in a position of power. When drinking together, he suggests heading from the bar to the bedroom, alone, preferably with same-sex chaperones. No visiting opposite-sex colleagues at home alone. No comments about women colleague’s sari or nail polish. “Ten years ago I didn’t have to give such suggestions. Now the law is reshaping people’s attitudes, so behaviour has to change,” he says.

Still, discourses are shaped by the powerful, not the marginalised, which is why men expect women to allay their ‘fears’. “My advice—men must learn to exercise restraint. Women will survive without your sexist jokes, keep them to yourselves. If a woman can learn that she cannot go for a walk at midnight, then a man can learn to change too,” says Grover.

A new protocol to control behaviour is thus necessary because at the root of the issue is desire. This, of course, puts an end to a certain kind of spontaneity, to self-censoring. “Men are more mindful and watchful. The conflict arises because the law tries to police desire, the foundation of erotic love, which can prove impossible to control,” Mehta explains.

Conflicts can sharpen with public figures, who enjoy a form of power. Shamir Reuben, a rising star in spoken poetry circles, was accused of sexual abuse by scores of women a month ago. When the incidents took place a couple of years ago, some of the complainants were minors. “I knew Shamir well at the time. He had told me he had met a 16-year-old girl. I didn’t interfere because he made it sound consensual,” says a former female co-student. With time, Shamir seemed less benign as other 16-year-olds surfaced in his narrations. He was already an adult at the time. One day, he tried to “push his tongue down my throat,” says this former friend, now 22. She kept away from him thereafter. Then, many months on, she “forgave” him and resumed friendly contact. “I felt I was making too much of something—so many people had anyway said I was over-reacting.” But once the stream of accusations emerged on social media, she regretted her ambivalence. “I should have spoken out long back. Now I joined the others in speaking out,” she says.

Within her close-knit circle of people who knew Shamir (he did not respond to a request for comment) they are not as forgiving of Harnidh Kaur, a young policy wonk and writer, who was known to be a close friend of Shamir’s and has a large social media footprint. Harnidh did speak out against Shamir on Twitter and is no apologist for the “old boys’ network” either. But her statement was not perceived as strong enough and she faced some serious whiplash on Twitter. But Harnidh herself is critical of ‘older feminists’, a term born after some experienced feminists differed with the MeToo method. “There is a crucial difference between being told I was not speaking out strongly enough against Shamir and Nivedita Menon, who used her platform to absolve an offender (Lawrence Liang) and hit back at those accusing him with remarks like ‘fingertip’ feminists,” she says. (Liang, a professor at Ambedkar University, told Outlook: “I am appealing the process, and so I am bound by confidentiality.”)

The case against Shamir was built entirely on social media—with volumes, veracity didn’t remain a concern. But complainants say it’s not about seeking retribution. They chose the online medium because they lack faith in police and courts, where it’s often the victims who suffer the ignominy of being named and shamed. “I think it’s usually just about closure,” says a complainant, a young woman who was one of the first to speak out. “Talking about it helps let go and move on.”

“People who oppose women speaking out on public platforms about abuse discount the power of catharsis,” adds Harnidh. “I feel if even that much was done for women who spoke out it amounts to work done, mission accomplished.”

By Pragya Singh in New Delhi

Tags