It hasn’t been easy for even his fellow lawyers and close observers to fully understand the maverick, who, to many, is as much a distasteful character as he is fascinating. All they know is that the episodes relating to Justice C.S. Karnan’s contempt case are yet to unfold fully—it’s an epic that is far from over. Is he a tragic hero or a villain? An idiosyncratic professional or plain insane? It’s tough to explain what exactly he was trying to achieve and why.

Court Of The Absurd

In mythology, the Sun God’s son is a tragic hero. But Justice Karnan, the first HC judge to be awarded jail term for contempt of court, has set a sad precedent.

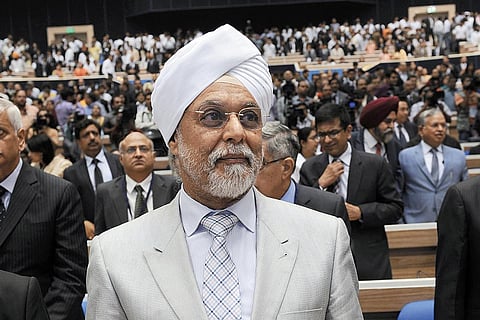

Justice Karnan’s cruise through many ‘firsts’ culminated into a historic order the other day. On May 9, the Supreme Court sentenced him to six months’ imprisonment on contempt charges. The order by the seven-judge bench, led by the CJI Justice J.S. Khehar, did not clarify whether the imprisonment was simple or confinement to a ‘civil prison’.

That anyway wasn’t the sole legal option. Another would have been to impeach Justice Karnan for misconduct, but the 59-year-old would have retired (in June) even before the lengthy proceedings really began. Apart from contempt proceedings, there are few ways for the apex court to discipline a judge, especially when he goes rogue.

On May 11, Justice Khehar said he would hear advocate Mathews Nedumpara, who appeared on behalf of Karnan in the Supreme Court, pleading for relief. In the past, the CJI refused to entertain the body Nedumpara represents: the National Lawyers’ Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Reforms. The CJI had pointed out that a contempt case ought to be between the court and the contemnor. Pending this, Justice Karnan has evaded arrest, while the police of at least three states are hot on his trail, amid incredulous rumours such as he may have even left the country.

The contempt proceedings against Justice Karnan began this January. Over the four months thence, he answered the apex court mostly through letters, notices and interviews in the media, which attorney general of India Mukul Rohatgi described as “scandalous”.

The SC, in its order, has also prevented the media from publishing further statements made by the judge. This placed a condition of ‘prior restraint’ on the media, completely blacking out anything that Justice Karnan may have to say, including a press conference he had called in Chennai following the court order.

A day later, Justice Karnan had convened a press conference in Chennai, but that went unreported due to the restraint order. He also held parallel proceedings in his quarters in Calcutta, where he was a judge with the High Court, convicting the CJI and seven other SC judges on multiple charges.

Karnan has accused his brother judges of caste-based discrimination, improper behaviour, sexual misconduct towards an intern and corruption. His ire was particularly directed against sitting Supreme Court judge, Justice S.K. Kaul, who had been his chief at the Madras HC.

Those who were part of his selection process, later disowned Karnan, including the then CJI, Justice K.G. Balakrishnan. This has added another question mark to the alleged opacity in appointments to the higher judiciary. Justice (retd) A.K. Ganguly, who had suggested his name to the Madras High Court collegium, reportedly said he was probably misguided, but a good man.

“He was representing a particular caste that should have been represented in the choice of judges. Therefore, I thought he should be considered,” Justice Ganguly had reportedly explained while denying that he knew him personally.

There were more serious complaints Justice Karnan sent to the National Commission for Scheduled Castes, claiming that he was being targeted as a Dalit. While these charges have still not been probed, the higher judiciary has often been criticised for filling its ranks from the upper castes.

CJI J.S. Khehar’s bench sentenced Karnan to imprisonment

“Had Justice Karnan been a judge from a higher caste, things would have been different,” says Paul Divakar of the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights. “In the last six months, we had tried to reach out to him, but could not. We wanted to ask him to lie low and use the regular procedure to pursue his discrimination complaints.” The activist rues that Justice Karnan made himself a target instead of highlighting the issue of discrimination. “That was because of the way he has used the judicial process. Now it has become too murky and we don’t know how to take it up.”

In another case, Divakar says his organisation helped a junior judge who had complained of atrocities by Justice Nagarjuna Reddy of the High Court in Hyderabad. “There were petitions to the Chief Justice and others, but without any action. A notice for impeachment motion with signatures of 53 Rajya Sabha MPs is lying with the chairperson of the upper house for the last six months, but it hasn’t moved.”

As for Justice Karnan, there have been several complaints by and against him. This led Justice T.S. Thakur, as the CJI, to pass an administrative order 14 months ago. In February 2016, Justice Karnan was thus transferred to Calcutta High Court. This, some said, looked like a knee-jerk move to deal with the trouble he was causing in Madras.

Karnan responded with a judicial order of his own, staying the transfer and called for a press conference. Court reporters tripped over each other on the way to his chambers because neither had they ever been invited in for a press briefing, nor had they heard of an HC judge staying a CJI order. Justice Karnan’s bosses in the Supreme Court pulled all judicial work from his court, which finally forced the judge to shift to the West Bengal capital.

In the Calcutta HC, Justice Karnan had a public spat with a same-bench judge who had denied bail to an accused in the infamous Vivekananda flyover collapse. Justice Karnan went back to his chambers and changed the court order, granting bail to the accused.

In January this year, Justice Karnan sent a list of 20 judges in a letter (which he also made public) to the prime minister. Without providing any evidence, he claimed that investigative agencies would find evidence of corruption if they “interrogated” these judges. This wasn’t something the Supreme Court took lightly. It initiated contempt proceedings. For the first time, a sitting judge of the High Court was asked to come to the court and answer charges of contempt.

Two weeks before Justice Karnan’s letter, retired Supreme Court judge Markandey Katju tendered an unconditional apology for his comments on social media, criticising an apex court judgement on a murder case. Sources reveal that renowned jurist Fali Nariman had agreed to represent Justice Katju after imposing a temporary ban on his social media criticism of the judiciary. “How does the judiciary respond to social media criticism?” former solicitor general of India Gopal Subramaniam had once remarked. Senior advocate K.K. Venugopal suggested that the SC should let the matter fade away since Justice Karnan would retire in June.

Despite his attempt at reaching out, the government did not show any empathy to Justice Karnan. Assuming that the attorney general was speaking for the government, it appeared to be the contrary, since Rohatgi appeared in favour of strict disciplining of the judge.

Recently, senior advocate Raju Ramachandran wrote how, in 1964, the chief justice, the attorney general and the prime minister of the time had quietly asked a judge to resign when they found him mentally incapable of continuing.

But, Justice Karnan’s responses to the SC judges made it difficult to reach some middle ground.

When Karnan did not show up, the SC issued a bailable arrest warrant against him. The warrant was served by a profusely sweating director-general of the West Bengal police under security cover of about a hundred policemen, even as Justice Karnan ranted at the TV cameras. He also sent a legal notice to the SC judges asking for compensation of Rs 14 crore for taking away his work and causing him distress. He later ordered the CBI to probe the judges and also passed an order restricting the seven SC judges from travelling out of the country and asked them to appear before him.

In another letter, Justice Karnan again claimed that the contempt case against him was an atrocity against a person belonging to a Scheduled Caste. “As a lawyer,” said senior advocate Ram Jethmalani in an open letter to Justice Karnan, “I have worked all my life for the backward classes and I have great concern and sympathy for them. But you are out to cause the greatest damage to their interests.” He also urged him “…to withdraw every word he had ever uttered and humbly pray for pardon for every stupid action you have so far indulged in”.

Later, Justice Karnan did appear in court pleading that his judicial work be restored and apologised, but would not drop the allegations that he had made.

At a point, Justice Karnan said he was not in a good mental condition. The CJI suggested that he get a medical certificate and later passed an order directing a medical examination of his mental health. Karnan later drove away a medical team that had landed at his doorstep in Calcutta for the examination.

It is not that there is no room for judges to get their grievances addressed or to change the system. Sitting among those seven judges was Justice J. Chelameswar, a member of the collegium who had challenged its opacity in the selection of judges. Being one of the four puisne judges, he opted out of collegium meets and insisted that the files for judicial appointments be circulated with written comments and observations.

Years from now, this bizarre event in India’s judicial history will be quoted. Whether it would be as a precedent or as an aberration remains to be seen.