For journalists in India, the only experience of nationwide state-enforced press censorship came with the internal Emergency promulgated by Indira Gandhi on June 25, 1975. I had just taken over as editor of the magazine Onlooker in Mumbai, and my first issue was ready to go to press. It was my maiden job as editor. Having cut my teeth as a newspaper reporter, I immediately got down to transforming Onlooker into a hardnosed news and features magazine.

Crawling Through The Emergency

In April 1976, <i >Fulcrum</i> Magazine did the only expose of the brutalities of Sanjay Gandhi's pet mass sterilisation programme. Its editor recalls his experience of press censorship in those infamous times — and on the million tyrannies now.

The cover story for my first issue was to be on Jayaprakash Narayan's 'Total Revolution' campaign seeking to overthrow the government through street mobilisation. The issue was to carry other critical features, such as a lengthy interview with Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then a leading figure in JP's movement, and an insider's expose of the Indian Foreign Service.

The timing couldn't have been worse. When I reached my office on the morning of June 26, I was told that the Maharashtra government had called a meeting of editors. Seated in a nondescript committee room, we were informed by a dour bureaucrat that we were no longer free to publish what we liked. A new office of chief censor was to be set up, and this worthy would henceforth decide what the people should read.

The whole idea seemed so strange that as we shuffled out of the room some of us sidled up to Sham Lal, the formidable editor of the Times of India, seeking a pointer for the morrow. A senior editor mustered up the courage to ask him what he planned to write in his next editorial. "I'll be writing on potato cultivation in Lahaul," Sham Lal, arguably the most influential editor in the country, replied tersely.

The bad news sank in — the world had suddenly changed.

Throughout the 21-month Emergency, the TOI never once fell out of line. The only note of dissent came from a single, much-celebrated item anonymously placed in the paper's 'Deaths' column by an outside journalist, Ashok Mahadevan:

O'Cracy, D E M, beloved husband of T Ruth, loving father of L I Bertie, brother of Faith, Hope and Justicia, died on June 25.

A year earlier, Mrs Gandhi had already shown her desire to control the print media by setting up a committee to inquire into the ownership pattern of newspapers. This was clearly a ruse to hit back at newspaper owners who opposed her. Distrust of the press was ingrained in her Congress Party, particularly amongst left-wing leaders. It was also a family trait — both her husband Feroze Gandhi and her father Jawaharlal Nehru, who probably coined the memorable term 'the Jute Press', were very critical of "monopoly ownership" in the media.

The Emergency showed how these easy labels could be so misleading. The erudite Sham Lal and the TOI group accepted press censorship without a whimper. K.K.Birla's the Hindustan Times surrendered even more abjectly. But amongst those who defied Gandhi were the boorish Ramnath Goenka of the Indian Express and the megalomaniacal Cushrow Irani of the Statesman.

The other surprise was Bhabhatosh Datta, venerable chairman of Mrs Gandhi's press ownership inquiry, which was known simply as 'The Fact Finding Committee', a name straight out of Kafka or George Orwell. Datta, a retired economics professor from Kolkata's Presidency College, submitted his report in 1976 at the height of the Emergency. But much to everyone's surprise, he refused to play Mrs Gandhi's tune — the report in fact concluded that the pattern of ownership of the Indian media suggested good competition rather than monopoly ownership.

So the first lesson of press censorship during the Emergency was: the most powerful need not be the most resistant to state repression.

But if the responses to the Emergency were uneven (while some journalists went to jail, a majority did what L K Advani later accused them of: "When asked to bend, you crawled"), my experience soon showed that even the exercise of press censorship by officials could be erratic and irrational.

Onlooker was put under total pre-censorship. In other words, every article had to be cleared by the censor before publication. As an inge?nue editor, I would struggle to find meaningful stories that could escape Big Brother's red pencil. One such was a long interview with the historian B N Pande on communal violence.

Pande was in the habit of visiting places that had been engulfed by Hindu-Muslim conflagrations. His interview was full of interesting anecdotes and observations. For instance, after the 1969 Ahmedabad riots, he found that a marauding Hindu mob had burned down all the Hindu shops at the edge of a shantytown, but the Muslim homes within the colony were left untouched. Puzzled, he asked the Hindus what had happened. They told him that an armed mob had come from outside and asked them to point out Muslim homes in the basti, and when they refused had threatened to set fire to their shops. They had stood firm, provoking the mob to go on an arson spree. Pande asked the Hindus why they hadn't protected their livelihood by simply pointing out the Muslim homes. "We're all from the same village in Rajasthan,”" the now impoverished Hindus told Pande. "What face would we have shown back home if we had betrayed our Muslim brethren?"

Pande's story spoke of the courage and decency of ordinary Indians. But to my utter surprise, the interview came back heavily censored, including the above-mentioned incident. The chief censor in Maharashtra was Binod Rao, a retired newspaper editor. I went to ask him why the Pande interview had been so brutally hacked. He read it with a pained expression, and finally confided: "The official who censored these pages belongs to the RSS. I can't over-rule him completely, but I'll restore most of his cuts."

I thought it was ironical that while the RSS had been banned and many of its workers jailed during the Emergency, an RSS man was sitting in the chief censor's office in Mumbai deciding what Indians should read. Was this what the French philosopher Foucault meant when he characterised censorship as not just a repressive but also a productive act — in this case propagating a hate-filled vision of India?

So the second lesson of press censorship was: when a state turns autocratic and repressive, it helps various tyrannical ideologies to bloom. As the sociologist Shiv Visvanathan put it, the Emergency was "a pilot plant, a large-scale trial for totalitarianisms and emergencies that came later".

Neither Mrs Gandhi nor the RSS though were responsible for the abrupt end to my first tenure as editor. Onlooker was owned by the Karnanis, a Kolkata business family with interests in jute and coal and whose name also adorned a Park Street mansion notorious for its brothels.

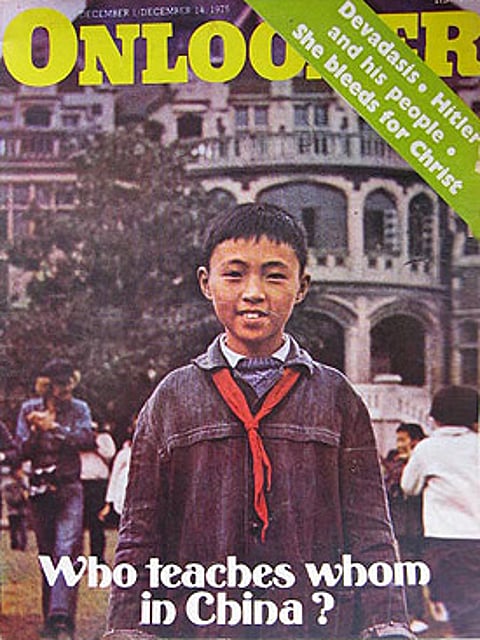

In my perennial quest for a little light in the dark shadow of the censor, I had carried a cover story on the success of the mass education system in China. It was very well researched and written by an Indian Marxist who had travelled across China and come back with excellent colour photographs, a rarity in the 1970s. In the gloom of the Emergency, the story seemed to carry important lessons for India's own, woebegone school system – it's another matter that it probably still does 40 years later!

But the Karnanis, with their Kolkata roots, detected a Naxalite conspiracy in the story on Communist China. It wasn't long before I was sacked from the Onlooker.

That was my third lesson: censorship often begins at home, even before the state steps in. The owner, no matter what his background, will seek to impose his prejudices on a publication. Look at what happened to the Hindu under N. Ram some years ago: on the one hand it displayed courage in publishing the Wikileaks files; and on the other, it did not permit correspondents to criticise China or write favourably about the Dalai Lama and the Tibet struggle.

My next experience as an editor pushing against censorship's shackles during the Emergency had an altogether different denouement. When I was editing Fulcrum magazine, we heard of forced sterilisations in a rural market town called Barsi in Maharashtra. I went there to discover the full horror of the national family planning campaign — hundreds of peasants who visited town on market days were dragged to hospital and forcibly sterilised in order to meet the annual target. Some were unmarried, some newly married and without children, some quite old. A brave local studio photographer had clicked the chaotic street scenes.

'Barsi — Success or Excess?' appeared as a cover story in Fulcrum, illustrated with photos of peasants being dragged into municipal vans. The sterilisation campaign was a pet project of Sanjay Gandhi, so there was no knowing how the government would react. The story got some play in the international media — the Washington Post even sent an undercover correspondent to Mumbai. But the knock on the door came some weeks after publication. Two Special Branch men walked into the office and enquired about the story. However, they seemed mainly interested in confiscating the photographs. I lied and said all the photos were at the printing press. They accepted my lie, and left. I never saw them again.

Barsi (now spelt 'Barshi') is located in Marathwada, a region to which the then Maharashtra chief minister Shankarrao Chavan belonged. The rural elite in the state had been outraged by the forced sterilisations. I was certain that the genteel behaviour of the Special Branch men when they called at the Fulcrum office had a lot to do with the feedback Chavan had got from his rural supporters. If I had done the story out of Delhi, the police response may have been altogether different. In those days, before Internet and satellite news TV, Mumbai was still far from Delhi, and Sanjay Gandhi's goons.

So the fourth lesson in state repression of the media: sometimes, its intensity can be in inverse proportion to the leader's links with the people. Chavan knew the Fulcrum sterilisation story expressed genuine grassroots anger; Sanjay Gandhi wouldn't have known that. Ultimately, the irony of this divide may not have been lost on Mrs Gandhi when she later looked back on the Emergency: press censorship ensured her insulation from the people, making her unaware of the popular rage against forced sterilisations. Smug in the belief of her own invincibility, she called a general election in 1977 and was resoundingly defeated.

The Indian media has undergone a dramatic transformation since that time. The print media has multiplied and boomed. Television has turned private and aggressive. And the Internet and social media now provide a radical way of disseminating 'news' and 'views'.

But along with this new spring has come another insidious blight. Rajeev Dhavan, the noted Delhi lawyer and free speech advocate, calls it "the new 'censorship' of communal intolerance through any legal or illegal means". He believes the destruction of the Babri Masjid in December 1992 marked the beginning of this disturbing phase, though there were some warning signals even earlier — such as the alacrity with which the government banned Salman Rushdie's novel Satanic Verses in September 1989. These high-decibel communal campaigns variously targeting newspapers, magazines, TV channels, books, art, cinema and music — in other words, the entire panoply of cultural production – constitute the biggest threat to freedom and democracy in India. And ironically, as Dhavan points out, "the new 'censorship' is as much the creation of democracy and development as it is simultaneously antithetical to it".

I realised this when the Hindu radical campaign protesting against a sketch of the Goddess Saraswati by the painter M F Husain began in 1996. Until his death in 2011, with the state mostly acting as a mute spectator, the celebrated artist's entire oeuvre was condemned; his paintings slashed and museums ransacked; cases filed against him in court; and his life and limb threatened, forcing him to seek asylum abroad.

During this period, Husain had also become a favourite topic of discussion — some would say, whipping boy — on TV talk shows, with the participants often displaying little understanding of either Husain as an artist or indeed of modern art itself. It seemed to matter little that for Husain, whose work was deeply influenced by Hindu iconography, inspiration for the controversial Saraswati sketch, for instance, had come from an 11th century icon of the goddess in the magnificent Vimal Vasahi temple at Mount Abu.

But of course, art was never the context of the vicious anti-Husain campaign; it was communalism. As the then Bajrang Dal chief told me back in 1996, the point is not what approach the artist takes towards his subject, or which aesthetic tradition influences and inspires him. The point is much simpler — "a Muslim has no right to paint our gods and goddesses".

Nor was the campaign to gag, bind and quarter Husain new — it only acquired dramatic dimensions due to a vibrant media and resurgent Hindutva radicalism. One leader of the campaign pointed out a letter by him published in Khushwant Singh's Illustrated Weekly around 1973 attacking Husain's paintings of Lord Ganesha. He was showing off his life-long commitment to the anti-Husain cause. But such letters were seen in those days as the outpourings of cranks, providing some entertainment on the readers' page. Now the farce has not only become serious, it is threatening to turn into a tragedy.

If proof were needed that besides bigotry and hatred, behind such 'new censorship' dramas there also lurks cold political calculation, one need look no further than the successful Shiv Sena campaign to get Rohinton Mistry's Such A Long Journey removed from the University of Mumbai's BA syllabus, ostensibly for describing the Sena as 'fascist'. The 1991 novel had been on the syllabus for years without anyone objecting. It's only after Sena founder Bal Thackeray's grandson Aditya was anointed head of the party's student wing and was looking for a suitable 'cause' to promote himself that he burned Mistry's book at the university gates in 2011, catapulting himself to national fame.

Can there be any doubt that the uproar against Mistry's novel was cynically manufactured by the Thackeray clan to project Aditya and mobilise Sainiks behind him, just as the campaign against Husain's paintings was designed to mobilise 'devout' Hindus against 'iconoclastic' Muslims? Therein lies the real long-term danger of this 'new censorship'. As Dhavan points out, this perilous trend is "the creation of democracy and development". It is also an instrument that political parties use from time to time to respond to sectarian grievance and whip up 'popular' support.

And the nature of the beast is such that the more free speech advocates confront it and the more the media report this confrontation, the bigger the beast becomes. Indian democracy is facing this existential dilemma only because the state often abdicates its responsibility to defend freedom and keeps surrendering to the mob. And this happens not because the mob is too big or too dangerous (we're still not Pakistan), but because the organs of the state lack conviction and leadership in order to be able to effectively defend freedom.

Let me take an opposite example to illustrate the point that the spectre of this 'new censorship' has grown mainly due to the passivity, nay cowardice, of the state.

Art galleries participating in the India Art Summit in Delhi in January 2011 were threatened that if they did not bring down Husain's paintings they would be attacked. As the art fair opened, all of Husain's works were hurriedly brought down by both Indian and foreign galleries. But for the first time ever in the long-running anti-Husain hate campaign, the state took its responsibilities seriously. The home ministry assured the organisers of proper security. Policemen were stationed at all the galleries showing Husain's works. The Delhi police commissioner visited the art fair to send a clear message that at last the government was ready to use its enormous resources to confront law-breakers. Record crowds showed up at the India Art Summit, and there were long queues to see Husain's works. Not one viewer attacked any painting.

There are of course many other internal and external threats to the media in India today — the insidious growth of 'paid news'; the increasing influence of powerful lobbyists as revealed in the Niira Radia tapes; the troubling impact of secret investments in media houses by big business, especially in television; the continued attempts by ministers and officials to hobble the media, as evidenced, say, in attempts to suppress or even murder journalists reporting on human rights abuses. All of these pose a big challenge, but none as bigger as the 'new censorship' of intolerance which, as Dhavan observes, "relies on coercion to silence the exercise of democratic free expression in a secular society".

Is it any wonder then that even a leader like Advani, who contributed to the rise of these forces of intolerance, is now worried about a second Emergency?

Maseeh Rahman reports for the Guardian, London, from Delhi. He first wrote about the Emergency and press censorship for an Infochange Agenda Special.

Tags