“...Enough of arguments, after all I am a stone pelter I cannot win an argument with you, for you are learned men and what else can I do to express my resistance against oppression.”

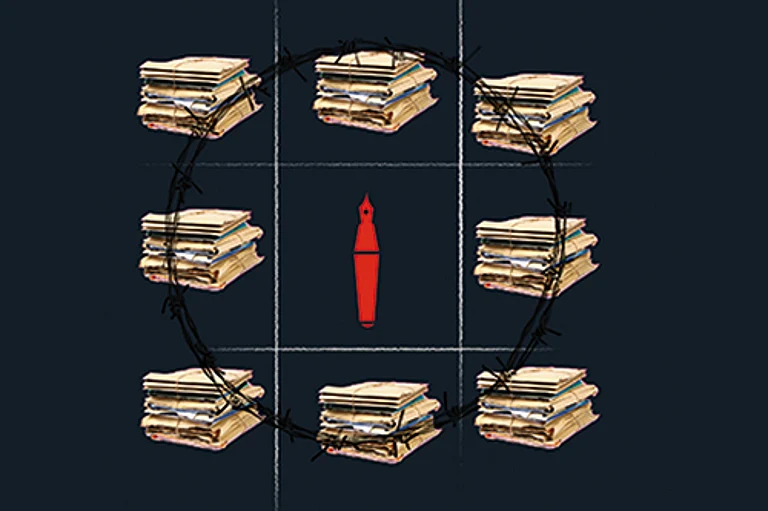

Poetry Of Protest: The Voices Of Young Kashmiri Poets

Young poets of Kashmir, mostly in their twenties, remain largely unknown. Some are aware of the risks of antagonising authorities with their poetry, but they continue to write

-Imran Muhammad Gazi, I Am a Stone Pelter, Greater Kashmir, 13 February 2010

Stone pelting, once the defining act of resistance in Kashmir, has been absent for the past few years. Does that mean resistance is over? No, it doesn’t. Resistance exists beyond stone pelting and street protests.

Words exist. Poetry exists. Poets exist. Poetry in Kashmir has become a rallying cry, giving voice to the collective pain and suffering through the ages.

Each poet has a personal story of the conflict that resonates in every poem they write. These young poets, mostly in their twenties, remain largely unknown. Some are aware of the risks of antagonising authorities with their poetry, but they continue to write. We spoke with some of these poets, who shared their stories, poems and passions.

Zeeshan Jaipuri

Zeeshan Jaipuri, 29, grandson of noted Kashmiri Urdu poet Syed Akbar Jaipuri, began writing poetry at a young age. He holds a master's in English Literature and is currently pursuing another in Urdu Literature.

His poetry, once focused on nature, love, and beauty, now speaks of darkness, night, blood, and death.

June 11, 2010 changed his poetry forever. That was the day that Zeeshan witnessed the death of his neighbour Tufail Mattoo near a sports stadium in Srinagar's old city as he walked home from a tutoring session for school. "I saw a tear gas shell fired at Tufail at close range, shattering his skull," Zeeshan recalls. "The trauma of that moment will never fade."

It was the time when anger was brewing across Kashmir against the killing of three civilians killed in what was reported to be a staged encounter by the military in a remote mountainous area in north Kashmir.

"Like Tufail, the blood of many was shed in the homeland, for politicians to shake hands again and pretend nothing ever happened," Zeeshan says.

He writes:

Mere Zeeshan, chup rehna, yahan se tez jharnon ne

Lahoo ko dho lia hoga, yahan qabrain chupane ko

Yeh susan bho lia hoga, mere Zeeshan, chup rehna.

(My Zeeshan, remain silent, here swift streams would have

Washed away the blood, here graves are hidden

By growing Lilies over them, My Zeeshan, remain silent.)

Mere Zeeshan, chup rehna, kisi se baat mat karna

Kisi ka khoon behta hai, kisi ko dard hota hai

Koi gir kar tarapta hai, inhen araam hota hai

(My Zeeshan, remain silent, don't speak to anyone

Someone's blood is spilled, someone feels pain

Someone falls, pleading, they (the oppressors) find comfort)

Zeeshan expresses dissatisfaction about the lack of representation in decision-making processes affecting the region. "All decisions about Kashmir were made without involving us," Zeeshan says. "We are left uncertain about what lies ahead."

Naheen pata kahan ki simt chal raha hai Karvaan

Naheen pata kis jagah pe ruk gayi hai dastaan

(Unknown is the direction where the caravan is headed

Unknown is the place where our story has come to a halt)

Chaman ki har kali kali lahu se lal lal hai

Zehn pe har shab-o-sehar ajeeb se sawal hai

Sawal hai ke kis tarah se pyas ko bhujhaen ge

Sawal hai ke raah bar kahan ko leke jayenge

(Every flower in the garden is stained with blood

Mind is filled with strange questions every night and day

The question is, how will we quench our thirst?

The question is, where will our leaders lead us?)

Zeeshan, along with a group of poets, launched "The Kashmir Tales" website in 2019 to provide a platform for budding poets and writers. Zeeshan explains, "We want to tell future generations that there were people who documented what happened to us."

However, due to resource challenges, the website was shut down. Zeeshan assures: "We will resume soon."

In the meantime, Zeeshan and fellow poets organise offline Mushaira sessions, where poets gather to recite their compositions. They invite poets from across the valley to share unpublished work, providing a safe space for creative expression.

Zuha

For Zuha, a 24-year-old literature student from northern Kashmir, writing poetry is not just an artistic expression but also a way of coping.

Zuha's poem, "THE LAND OF IRONIES," explores Kashmir's dystopian reality. "The irony lies in being demanded to surrender to peace with guns pointed at your chest, while your humanity, identity, and dignity are stripped away," she says.

Zuha's poem reads:

A hand that cut you to pieces

Might offer you a band-aid

A cannon pointing at your head

Calls your silence “peace”

And bullets teach the birds how to fly.

The kids fall asleep to the sound of gunshots,

And wake up searching for the lost faces.

The walls of their blown up homes

Become their last defence,

The stones in their hands.

And they grow up dying, little by little,

And the only thing alive

Is this flame in their eyes.

The flame that holds the memories,

That burns the wound to stop blood loss;

The flame that keeps them on their feet,

The flame that can char this hell to paradise.

Zuha has also self-published a book, 'Sermons of the Fallen', a collection of her poems. One of the poems in the book, written during the post-2019 lockdown, is titled "DEAR HOMELAND." She says she wrote it out of "sheer helplessness."

"At the end of the day, regardless of how much we write or talk about it, we aren't helping the practical situation," Zuha says,

The Poem reads:

I speak not the language of bullets and bombs,

So I doubt if you would understand me.

Upon the oblivious ears of vanquished carcasses,

My shallow survival songs fall.

Why do I write to you?

Why do I wander in your deserted streets . . .

Beloved, I have not tried enough, yet I am weary; unhand me!

With love, and sins,

And no ounce of repentance,

Keashur, (in these lands,

A human, in others.)

Ali Masroor

Ab yahan sab kharab achha hai

Ab meri jaan azab achha hai

(Now everything bad is good here

Now, my love! the torment feels good)

Yar o ghair ne hamein luta

Hans rahe hain janab? Achha hai

(Friends and strangers have looted us

Are you laughing, sir? It's good)

In these verses, Masroor, 23, consoles himself, telling himself to come to terms with the status quo. Deep down, he knows that it is the struggle that keeps resistance alive.

Masroor has always been drawn to Urdu poetry, but his words once flowed with a different essence. As a child, his verses revolved around God and spirituality. However, life had other plans.

In 2010, a school bus from Masroor's school was torched during protests. Two days later, upon returning to school, he saw a kindergarten student with golden hair and blue eyes severely burned on the face and neck. The child had been left behind after the burning bus was evacuated.

"The image of that little cute boy's burned face is etched in my memory," Masroor recalls. "He didn't understand Azadi. For him, it meant playing with friends in the park for longer. He was oblivious to the idea of nation and anti-nation.”

Now studying Urdu Literature, Masroor began questioning the realities of ‘curfews’, ‘crackdowns’, ‘interrogations’, ‘arrests’, ‘detentions’, and ‘hartals’ after this incident. These words shaped his poetry and perspective.

In his poem "Siyasat Ki Salah" (The Advice of Politics), Masroor critiques how politics demands conformity, particularly in the context of Kashmir.

The advice of politics, as Masroor puts it, is:

Khamoshi ki bayyat ko kar le qubool

Na kar ahtijaaj o muzaahmat bapa

(Accept and obey the narrative of silence

And do not oppose or condemn any acts)

Ghulami mein reh kar mu'arrikh kama,

Na sunna aseerun ki aah o fughaan

(Be a slave and your name will be craved in the history

Don't lend an ear to the Wails of oppressed one)

Utha apne Kaanon mein rakh ungliyaa'n

Vo duniya mai mash'hoor hojaenge

Jo halmin ko sun kar bhi sojayenge

(Put your fingers in your ears and ignore their pleas

For fame will be found by those,

Who stood silent even after hearing the cries of plight)

Zahra

Zahra, 21, started writing about conflict in 2016, in the aftermath of Burhan Wani's killing when she would see the names of young people being killed in newspapers.

"If you put a 7th-grade student somewhere where she hears shell and firing sounds daily for months, it'll be traumatising for her. It takes and stains a part of your childhood," she says.

Zahra adds that when she sees young people playing online games with bullet sounds, she feels traumatised. Her cousins now avoid playing such online games around her.

Zahra has written a poem titled "I Promise," dedicated to brothers beyond blood relations. Zahra explains, "It's the brothers my motherland gave me, and those who suffered for my motherland."

My brother! I will forever mourn your pain

I will remember you and that vermilion rain

I will recite fatiha for you and the one's who left

I will gather the pieces of her heart, I will fix that Painful cleft

I will write for you till the words start crying

I will make them recall the pain when you were dying

I promise I will visit the place where you rest

I will write and cry for you, in every freedom fest

Zahra has also written a poem about a child (herself) comforting her mother (Kashmir), a reversal of the usual roles. To her, "Mother" has a sacred and pious meaning. She says, “Mother suffers and endures all the pain for us, her children, she protects and takes the harm to her.”

O Mother!

Show me your scars and all that's unhealed

Show me the blood stains on your sacred skin

Show me the oppressed parts of you

And show me your eyes that bled red tears

Show me all that they did to you, Mother!

O Mother!

I'll protect you till I breathe my last

And I won't let anyone touch your pious self

I'll peel off my skin to cover your scars

I'll burn myself down to keep you warm

O Mother! Just don't wither away and die

Bariya Hamid

Bariya, a PhD scholar in literature in her late 20s, has always preferred writing, as she struggles with verbal communication. "I never felt I could convey myself well through speech," she says.

Writing started as a hobby, but soon became her outlet. "Living in Kashmir was a powerful catalyst." Bariya explains.

Kashmir inspired her, sometimes with its serenity, other times with its natural beauty and culture. On some days, it was the rage, anguish, fear, and dilemma that found expression in her words.

"Kashmir really became a backdrop setting or subconscious aspect that brought me to writing," Bariya says.

She writes:

I am an (un)occupied woman,

You try to silence under fear,

With every passing day

I am a witness

To an added tyranny,

How many more kins shall I mourn?

With my heart filled with dread,

I have still so much to lose,

The fear rooting deeper

With every force and game.

Bariya recalls a night which was ‘awfully’ quiet in 2019, during the Article 370 abrogation period, when she was ridden with anxiety. At that time, schools and colleges were shut, tourists were ordered to leave, telephone and internet services were suspended, and regional political leaders were placed under house arrest.

"I remember the angst, the fear, and the dilemma of if we will ever meet our families and relatives and friends again while also thinking how someone far away would be discussing at his table in all peace and we here are scared for life,” Bariya says.

My vicinity is silent too,

I wonder if anyone is living Anymore! Is any?

They shut the world against me,

Smoking my dreams

To butts of their cigarette.

I sit and stare

The walls my screening,

Fighting horrors of night

And torments of day.

Days are stretching to months,

Shall I see my people again,

If they live anymore?

Khansa Kubra

Khansa, 29, hails from South Kashmir's Pulwama. As a literary fellow at South Asia Speaks, she is being mentored to write her book of poems, which she is thinking of naming "Fish-Head." Her grandmother used to cook tasty fish, Khansa says.

For Khansa, the inspiration for writing poems about conflict came only after moving out of Kashmir and realising that life in Kashmir wasn’t very normal.

Khansa holds a master's degree in Literature from an institution outside Kashmir. "It was only when I encountered other people and places that I realised there were freedoms in self-expression and fewer anxieties than those present in Kashmir," she says.

Whenever she mentioned being a Kashmiri from Pulwama, she always met with the same response: "PULWAAAMMAAAAAA!!!!", accompanied by widened eyes and gasps.

“Everyone would react as if I had dropped a bomb,” she says.

The February 2019 Pulwama attack, which claimed the lives of over 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel, reportedly led to harassment of Kashmiri students in many parts of the country.

In her poem "All There's Left Is Storytelling," Khansa writes about the village in Pulwama she grew up in and its people who wanted to lead ordinary, simple lives, while a giant cloud of anxiety constantly loomed over them.

This year they are here again, the soldiers.

The spring air, rusty, pierces our eyes, leaves

dust on the leaves and our tongues.

The things we keep hidden escape in our sighs.

My grandmother, arthritic, with swollen feet, sits near the window

an old bird about to drop

to its death wanting

to cry for one last time.

She does this every year: says she'll go.

But she's at the window again

because the boys next door haven't returned

their mothers with bad hearts haven't returned

and the man with the pigeons hasn't returned.

Himayat Ali

Wal beh ghari beil aur kut gacsakh

Manz kaman loknai van ati basakh

Lod yimo maqbool afzal dar baam

Zindagi kut gzakh ati chie shaam

(Stay home, what for, are you leaving?

Among these kind of people, how will you find your home

The ones who betrayed even afzal and maqbool

Oh, dear life! Stay, for there's dark outside)

Himayat Ali, 28, writes these couplets in Kashmiri language to describe his resentment with his fellow Kashmiris who remain silent in fear while "everything is being taken" from them.

"This silence is a lie," he says.

Himayat, a carpenter from Central Kashmir, regularly visits a local library to study history and literature. He has been writing Kashmiri poetry for 12 years.

His passion for writing poetry began after his friend Arbaz was killed in 2008 in a protest. Himayat says his friend was not involved in the protest.

"We were playing, and while crossing the road amidst the chaos, I witnessed Arbaz being fatally shot in the head," he recounts, adding that even talking about it brings back dark memories from that painful chapter of his life. "I have never found a friend like him again. I miss him every day."

Himayat says poetry won't bring back lost lives or shattered homes, but it documents the struggle and resilience of his people.