Kashmir Speaks in Metaphors

A Silent Season In Kashmir

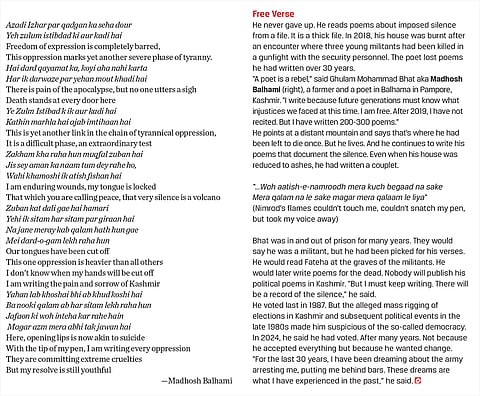

In the campaign rallies in Kashmir, political candidates from different regional parties spoke about breaking the silence. They said the abrogation of Article 370 took away their dignity. Now is the time to speak up, they said. People turned out in record numbers to cast their votes in the Valley. What does that mean? Is it acceptance or is it the act of breaking the silence? What is this silence?

In 2019, a man started making paper planes in another country far away from Kashmir, which had been sealed off from the world for months when the government abrogated Article 370, which gave Jammu & Kashmir a special status. It was done suddenly. Without any warning. Internet and phone lines were suspended. Silence descended on the Valley. People still wrap the silence around themselves. Everyone has their own reason and version of this silence.

Ehtisham Azhar, 34, an artist who was then doing his PhD in Australia, couldn’t reach out to his family.

He felt helpless. He remembered his childhood in Baramulla where he would make paper planes and fly them. It was an innocent act that manifested the desire to fly, to attain freedom.

He remembered they would sometimes write messages on the paper planes. That was his way of remembering his Kashmir. The audacity of the act of making paper planes was a commemoration of his homeland and the desire for the unattainable. “A paper plane is also silent,” he said.

Over the years, his work has dealt with silence and memory. In yet another work, there are photos of shirts hanging on trees in a graveyard as identifiers. These were the unidentified graves and he had seen the gravediggers hang the shirts of the dead as epitaphs. That’s how ideas of space and time and history are constructed. A scar is also an implication of an action, an archive, a memory. A scar speaks.

Kashmir speaks in metaphors.

Metaphor is the only language here. Extended, absolute and mixed metaphors.

“For me, this silence is not a negative connotation. There can be 10 voices saying all is well, but the silence is so abnormal that instinctively a person knows that something is wrong somewhere. That’s the power of silence.

“Silence is a language, if one could say that,” he says. Now, Azhar can’t return to Australia to defend his dissertation. His passport, like those of many others, was suspended last year. “Are you trapped here?”

Like in the unnamed island in the book by the Japanese writer Yōko Ogawa where boats have disappeared, and people are trapped where they must forget in order to live.

“If everything is normal and we are silent, why is there so much security still?”

“Kashmir shrinks in my mailbox.”

—Postcard from Kashmir by Agha Shahid Ali

Why do you ask about silence?

Silence is a language.

Ask no questions.

Do you guarantee anonymity?

There will be consequences if I speak.

I have said everything and yet, I have said nothing. The silence is good, no?

The time has come to break the silence.

This silence is like lava. It will burst. History is witness to this in Kashmir. Look at what happened in the 1990s.

Be quiet. And let us be silent.

Silence is survival.

Silence is powerful. It is resistance.

This silence is temporary. The weather here changes in five minutes. This is an unpredictable place.

Can you hear the silence?

Where do we go to break our silence? Who will listen?

Now, you can dance in Lal Chowk. That’s normalcy.

Tourists want to see where militants were killed. That’s there, too.

Silent Eyes. A bumper sticker on a car.

—Conversations in Kashmir

“A few kinds of vegetables, cars that constantly break down, heavy, bulky stoves, some half-starved stock animals, oily cosmetics, babies, the occasional simple play books no one reads… Poor, unreliable things that will never make up for those that are disappearing—and the energy that goes along with them. It’s subtle but it seems to be speeding up, and we have to watch out. If it goes on like this and we can’t compensate for the things that get lost, the island will soon be nothing but absences and holes, and when it’s completely hollowed out, we’ll all disappear without a trace. Don’t you ever feel that way?”

—Yōko Ogawa, The Memory Police

Every day, when the people on this island in the book wake up, something disappears from their memory. Here, the majority forget and the few who remember must keep themselves hidden from the Memory Police, a squad that is tasked with enforcing memory loss.

At first, ordinary things disappear. Then, birds and flowers and photographs and calendars. Then, people who can’t forget start to disappear and are taken away by the squad to unknown places in trucks. Those who are capable of forgetting lead “normal” lives because they don’t question anything and leave everything to fate. Disappearances are continual. And yet, life goes on and people fill their days with worrying about food and weather and who to trust and when to speak and what to risk and when and how to keep or break the silence.

Like in Kashmir.

How does one write about Kashmir’s silence? One must be careful about the metaphors one chooses because they can have implications. People here can testify to that.

Everywhere, everyone else is writing about Kashmir. They are invoking its history, they are talking to political leaders and they are listing the projects earmarked for Kashmir. Only the people are missing. Their stories are silent.

Like in the book where photographs and maps disappear, here in this place, stories have disappeared.

A former journalist talked about how his diaries had been taken away.

“Those were my personal archives. I had written something about the silence. I had said there is no news of news. Living here is like being in that book, 1984, by George Orwell. The penetration is deep. There is mistrust. There is fear,” he says.

In November 2022, his house was raided, along with many others.

“One officer asked me why my house has so many books,” he said.

They took him to the police station and that’s how the ordeal began. He would report in the morning to the police station and come back only at night. This continued for 11 days. He was abused and beaten up. But he remembered that, as a Kashmiri, they had been through it all before.

“We navigated the 1990s,” he said.

He was released later. But his passport is under review.

“I’d have written my story, but I think it is not a good idea,” he said.

Earlier that year, the Kashmir Press Club was forcibly closed. “I have told you everything and yet I have not said anything,” he said.

It was a strange time. It still is. A lot of his friends abandoned him. He had been tagged.

There is this silence between friends.

There are other changes, too.

They were aimed at memory.

In 2023, the University of Kashmir dropped three poems by Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali along with author and journalist Basharat Peer’s memoir from the curriculum of a post-graduate programme in English.

Shahid’s famous poems—‘Postcard from Kashmir’, ‘In Arabic’ and ‘The Last Saffron’—and Peer’s Curfewed Night were part of the syllabus in the third semester of the Master of Arts (English) course at the University.

Cluster University Srinagar decided to discontinue Shahid’s two poems, ‘I see Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight’ and ‘Call me Ishmael Tonight’.

“So, you now know that this is strategic. Silence is our coping mechanism. We are all vague. There is a sense of fatigue and defeat. Humiliation is settled deep within us. We, the storytellers, were branded as narrative terrorists. Stories are missing. It was khabar ki maut (death of news),” he said.

The digital archives of regional newspapers, including Greater Kashmir, Rising Kashmir, and Kashmir Reader, along with many Urdu language journals, were either partially or entirely destroyed, particularly after 2019.

At a newspaper office, the walls are adorned with framed editions from a time when editors and journalists wrote about the conflict and excesses on both sides.

But the editor says he stopped writing long ago and no longer reads his own newspaper. The front page is filled with agency bylines. On that particular day, the frontpage news covered an encounter in Tral, where two militants from the banned terror outfits Ansar Ghazwat-ul Hind and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) were killed by security forces. The two militants were identified as Safat Muzaffar Sofi alias Muavia of Ansar Ghazwat-ul Hind and LeT’s Umer Teli alias Talha. Byline: Press Trust of India (PTI).

That’s because we don’t want to be raided, he says, referring to the use of a generic agency report, instead of a staffer’s copy.

“Ask no questions,” he said.

That’s how it works now. A new stylesheet is in place. Unofficial, of course. But militants now have to be called terrorists. ‘Separatists’ is a deleted word. That’s one example. The archives have been deleted.

“I want to ensure people here have jobs,” he said. “We are enjoying the respite from news. We have learned to tread cautiously. All the working journalists have disappeared. There’s no politics in Kashmir. There are no watchdogs, no human rights activists, no politics. It is a rule now. We ask no questions. Media reflects the people. They are silent. We are silent.”

The editor looked out of the window. He said people are out in the streets late at night. There is no fear of the gun.

“This freedom has a price. Enjoy and don’t talk,” he said.

Long ago, there were the singers who sang about the unfreedoms, the bloodshed, the curfews. But Kashmir’s most popular hip-hop artist, Roushan Illahi, aka MC Kash, no longer sings. He stopped in 2019.

Another lawyer, a former human rights defender, had hidden his diaries to save them from the raids. On a fateful day, the diaries were sold off to a raddiwala by mistake. He tried to retrieve them, but they were gone.

“The silence has a cost,” he said. “There is despair and helplessness. Pakistan has been exposed. Kashmiris are expendable.”

In a worn-out building that has been painted recently, a man lit a cigarette and said he wouldn’t want to be quoted. There are consequences. He has chosen silence. Like many others.

This little ancient building isn’t far from the Ghanta Ghar (clock tower) which was recently renovated and is part of the massive makeover project in Kashmir. A makeover that seeks to erase a lot of other history here.

In Kashmir, the timeline is like a chewing gum that can be stretched, because that’s how long a day and night can be when there is so much silence.

There was an old building in Amira Kadal where enforced disappearances were documented and habeas corpus petitions were filed by families who were desperate to know the whereabouts of their sons, brothers and fathers had disappeared. This is the building where the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) was formed as a collective in 1994.

This is the building where the Jhelum Hotel once used to be. Later, the Kashmir Times newspaper office operated out of here. They brought out ‘Informative Missives’, a monthly dossier recording human rights violations. ‘Informative Missives’ continued its work until 2019. There is that silence after that. The people who worked there have disbanded. There is no civil society anymore in Kashmir. The Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society only exists online.

Offline, there is silence.

***

There is a lot of newness. New roads, flyovers, malls. This is Naya Kashmir. The ambition is to make this city that’s forever in transition, a place that can look like the rest of the cities in India. Homogeneity is a nationalist concept. All nationalism has a cost, a Kashmiri writer and professor said.

“People voted. Isn’t that an expression? When a political change comes, it takes time to absorb. People ask me why I voted. I want a government. This isn’t a betrayal of the original cause. Where is that utopia? Silence has a lot of dimensions. There is that ‘fetishization’ of Kashmir as a country without a post office. Agha Shahid Ali wrote that poem, but he was mourning for his class privilege. Nationalism brings silence. It is like either you are with us or against us. There was Kashmiri nationalism, too. It demanded a blood sacrifice. Silence here is in single quotes. We don’t know what our sadness is,” he said.

He had earlier insisted he would not want to be named. That’s how it goes, he said.

“You keep that part of the bargain and I will tell you about why I am silent,” he had said.

He is now a teacher at a government college, where he must ask students not to offend anyone. That’s a decree. Unofficial and pervasive.

***

That’s what they ask for before they speak. For anonymity. How does one tell the story of silence when nobody speaks? There are consequences. This is Kashmir. Not New Delhi, they say.

Isn’t that the story itself? Of no names and no faces. There is a kind of moral victory in this silence, leaving the outside world guessing. If there’s no freedom of speech and expression, let there be the freedom of silence, they say. There are all kinds of silences. Some say there are nine kinds. Others say there are more than a thousand.

There is the silence of fear, the silence of doubt, the silence of emptiness and it is here in Kashmir that you hear the endless echoes of silence.

Why do you want to write about silence?

The young woman asked. Her silence is for the sake of her future, for her unborn child, for love.

In March 2024, Ruwa Shah, ex-journalist and granddaughter of Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani, disassociated from separatist ideology, pledging loyalty to India. Jailed separatist Shabir Shah’s daughter, Sama, published a similar notice. Ruwa’s father, Altaf Shah, died in jail last year. She hopes for her passport to be renewed in order to join her husband in Dubai. But the passport remains an elusive dream. She is trapped like many others.

Artist Masood Hussain, 68, never left Srinagar. He thought he would spend his time “chronicling” life in Kashmir. But soon after the abrogation, he felt hope was fading. He painted Jawaharlal Nehru in conversation with Sheikh Abdullah, who held the title of Kashmir’s prime minister, discussing Article 370. It ended in doom. There was hope before. This was his response to what he calls the final betrayal. “I have not painted anything adverse. People are scared to talk. I just watch everything. I am still watching. We have to be very careful. I am waiting for a proper time,” he said. “It will come.” This waiting is part of life here. Hussain would tie wish knots at the shrines in the city of Srinagar. He never untied any. Wishes were never granted. He had wished for peace, for his friends, who had left during the insurgency, to return. “Development is not peace,” he says. “Nothing is normal in Kashmir.”

She wanted to live a normal life and thought distancing herself from her grandfather’s politics would free her of the burden of the legacy she carries.

“I am with child. My child deserves a chance,” she said. “The day I was born in 1993, there was firing outside. I never had a proper childhood. I can’t blame anyone for my high blood pressure. People can call me strong, but I don’t want to be. I want to be with my husband and raise my child.”

Despite election slogans about breaking the Valley’s silence, hope is scarce. Record voter turnout reflects a belief it might be their last chance to have a say, as separatists no longer call for boycotts.

At a gathering of fiction writers in Srinagar in a ramshackle hotel, a man said that it was their way to break the silence through fictional accounts where people can express their fears and hopes, talk about their losses. After the floods in 2014, there was a strange lull, he said.

“We founded the Fiction Guild to tell each other stories,” he said.

Later, a poet and a writer said that she thought her art had become purposeless. She has continued to write but doesn’t want to publish anything yet.

“We need to survive. All of us know that we are a small community and we have to fight against extinction first,” she said.

It isn’t the first or the last silent season here.

“With the abrogation, they took away our dignity. Nobody has ever asked Kashmiris what they want,” she said.

It is a soundless city. Srinagar, she said.

Outside the hotel, a journalist said everyone is Sisyphus in Kashmir. In Greek mythology, the king of Corinth was condemned eternally to repeatedly roll a heavy rock up a hill in Hades, only to have it roll down again.

But Sisyphus is easy, said Azhar, the artist. Franz Kafka even said that we must imagine Sisyphus to be happy, that there was some meaning and joy to his punishment.

“I think Kashmiris are like Prometheus,” he said.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus was bound to a rock and an eagle was sent to eat his liver, which the Greeks believed to be the seat of emotions. The liver would grow back overnight and then be eaten again by the eagle.

“Prometheus knew the secrets of the gods and he told them to the people. That’s why he was punished,” he said. “We are not rolling anything up the mountain. We are stuck to the mountain, driven back into the rock. Like I am one with this landscape.”

***

Within the chambers of a shrine in downtown Srinagar, the wailing of the women broke the silence. Their wails were pitched against the mighty silence that prevailed outside, kept in place with guns and security personnel in invincible-looking vehicles.

“We are ghamgir (in sorrow),” Khazara, an elderly woman, said. “Kashmir is full of grief.”

Why do you cry?

“I cry and the others cry because we are lost people. Someone has lost a son. Another, a brother. Someone is waiting for their husband. We cry because we can’t speak,” she said.

On another night, a woman peeked out of a curtain at a shrine and beckoned me. She tore a polythene bag and asked me to tie a wish knot. She was old. She comes here every night to pray for the dead and the disappeared. But do not write that, she said.

At Shah-e-Hamdan, the window bars have many wish knots.

“I am from here. Do not write what I have spoken because the police and army will come. We have witnessed this for years. Silence is our way of surviving,” she said. “I won’t vote. What will it bring to us?”

An artist once said that he had never been able to untie the wish knots he had tied at the shrines here.

“They weren’t granted,” Masood Hussain said.

***

Kashmir now feels like a depersonalised space, a non-place where tourists pass through a staged utopia of lakes, mountains, tulips, and roses. It’s a context-independent, anonymous landscape, devoid of history, where everyone is a stranger.

Everything is familiar and yet, there is a change of guard. I wasn’t here in the 1990s, when cinema halls had been closed by a diktat. Now, there is a multiplex here. The city is also a wedding destination. Paradise was lost. And now, regained. Concertina wires are still wrapped around it. Bunkers are still in their places. Armed security personnel look at everyone like they are scanning them. The city, in fact, feels like a vast scanner. I know they know. They know I know. The walls have murals about Kashmiri culture and the way of life. Then, there are giant flowers. Carpet weaving scenes, etc. These are new. A promised makeover, except when you venture into the alleys. There, you find signs that have been painted over. Leftovers from when the city’s people still protested. And inside some of the lanes in downtown Srinagar, the walls bear words like azadi and khilafat.

It is one Kashmir countering another version of it. Graffiti meets counter-graffiti here. And in between these two narratives, lies the truth of this place, which is unintelligible, like the signs and words and phrases like “Go back India” sprayed over by paint and yet, the words, dismembered and faded, remain. On the walls, a game is on, where the two sides alter the messages. It is mangled graffiti. “Go back India” becomes “Good India”, and in these alterations, there is a place going through cosmetic change. Even beauty parlours here now promise ‘makeover’.

It is a forever siege. A place in a limbo. Discredited, dismissed, deformed. But nobody will say any of this. They will instead say, why speak of silence when we can talk about the weather and the stray dogs barking late into the night.

“There are too many dogs here,” one man said. “A few even believe that India dropped them here. Conspiracy theories. That’s how we make up stories in this silence.”

****

Happy tourists are everywhere, taking photos, holding roses and tulips, and floating on lakes. But there’s a notable absence of protests or mourning. Families of the disappeared no longer commemorate their loved ones. Previously, on the 10th day of every month, they gathered with banners at Pratap Park, now a memorial for fallen army personnel.

There are many such stories of silence. A former resistance ideology supporter is writing a book about his neighbourhood. He recalls a boy struck by a bullet in 2010. Though he offers to share his story, he only shows others’ experiences, never his own.

That’s how it is. For now.

More than 8,000 people have disappeared since the 1990s. Nobody now knows where to look for them.

Nobody wants to ask anymore.

It is what the new normal is.

The disappearances are normal now.

Finally, the Ghanta Ghar at Lal Chowk now shows Indian Standard Time. For years, the clock didn’t quite work. Now, the bell rings in the new hour every hour.

There are many other stories. Many other conversations. But we have not recorded those for the sake of silence. As an ode to it. Out of fear, too. And out of superstition.

“What will happen if words disappear? I whispered to myself, afraid that if I said it too loudly, it might come true.”

—Yōko Ogawa, The Memory Police

(This appeared in the print as 'A Silent Season In Kashmir')

Tags