“Do you understand the sadness of geography?”

Heterotopia

A world within a world is running out of time. But the voices of McCluskieganj’s past continue to resonate within its ruins, even as development takes over

—Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient

This is an ambivalent place, a place that defies the rules of any order. Here, the stayers-on are storytellers. There is only the past. A past that is not just history, but also a lot of memory.

Time is experienced differently here. Michel Foucault outlines in his book Of Other Spaces that “Heterotopias are genuine locations that serve as ‘counter-sites’, symbolising, opposing, and inverting all other traditional sites, in contrast to utopias, which are imaginary, wonderful, and perfect surroundings.”

The Gunj is that. A place that was imagined as a utopia and later became the mirror in which the image you see doesn’t exist. In this place, there is a relationship between space, power, and resistance. Memory is its tool, its site. Its only identity.

Geographer and writer Yi-Fu Tuan argues that a place is more than a location, it is a space full of meanings and objectives. Like the Gunj that transitioned between two phases of modern international history and the nature of Englishness, assuming a cultural authority that, in turn, implies citizenship.

In this case, a place for people whose country is not on the map. It lies in the realm of dreams. A dream that was lived. Even if for a short while. And like all dreams, they woke up from them. The people, the ‘stayers-on’ as they are called, the Anglo-Indians who decided against leaving, call themselves a “people of nowhere.”

In his book Beyond the Map, Alastair Bonnett says that “a place is a storied landscape, somewhere that has human meaning. But another thing we have started to learn, or relearn, is that places aren’t just about people; that they reflect our attempt to grasp and make sense of the non-human; the land and its many inhabitants that are forever around and beyond us.”

The sadness of the Gunj hangs from the tall Sal trees, it looks out of the old windows of old houses, it lives in its people. It is a place forever beyond us. A place of loneliness. A refuge for the misfits.

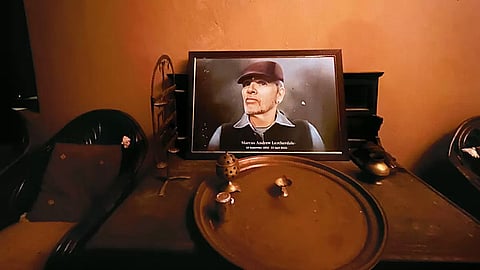

Marcus Leatherdale

He never wished to outlive his lover. That’s what he wrote in his last letter. Short notes with phone numbers of the relevant people scribbled underneath with instructions regarding his photographs and money. Does someone who has decided to kill oneself become so precise and poetic in letters that are meant for final goodbyes?

Marcus Leatherdale, a famous photographer, had hid these letters in the apartment of his former partner Claudia Summers in New York before he came to McCluskieganj. It is strange to think he had been planning to die all this while as he continued to rebuild and renovate the bungalow in McCluskieganj that he had bought many years ago.

But on April 22, 2022, the 69-year-old ended his life, according to his caretaker Kailash Yadav and the police. His body lay in the morgue for 12 days and almost rotted before they cremated him. His ashes were thrown in the Ganges. Everyone in the Gunj knew him. They have moved on but they still tell his stories.

Leatherdale came to India in the 1970s and kept coming here for years and bought a bungalow in the Gunj. He had met Kailash who used to be a tea seller in Varanasi and had taken him along on his assignments. It is a death that people in the Gunj haven’t reconciled with. Some say it is a murder and others feel the place got to him along with the other losses he suffered.

The film A Death in The Gunj also tells the story of a young man who kills himself while on holiday here. Death of the Gunj is now coming. They all know it. That’s the loss they have been preparing for. But they also know they are never prepared enough. Mines have come up and the Gunj is no longer what it was. More deaths will happen. Natural ones. And then who will tell the stories?

Bablu Paswan

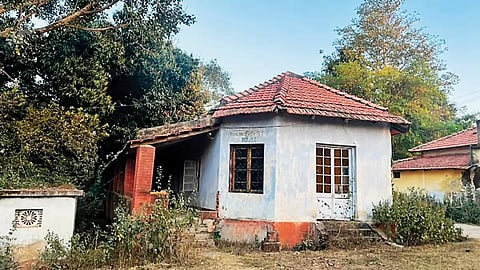

Since 1995, when he inherited this bungalow, Bablu Paswan has been trying to make sense of his inheritance of loss. The Potter Bungalow stands out. Yellow with sloping roofs and stained glass windows. Inside, the decay is pervasive. A photo hangs of Stanley Potter, a government employee. Next to it are his old hats.

Potter resigned from his job to look after his ailing parents and remained single although Bablu recalls he had been in love with a woman who had come down here for him. But Potter could never say it to her and she returned to wherever she had come from. These stories have been passed on from one to another and the rituals of remembrance are undertaken when a stranger comes to town looking for a lost homeland, a set of people who dared to dream and to find remnants that they can reconstruct a place with.

Memory, often treacherous, is what people here hoard. They have this locker hidden somewhere in their being from which they tell stories. The grandeur was never so grand here. Potter sold off his things later in life. A gramophone, furniture, crockery, perhaps. Aunty Ruby, another resident, remembers the old man tuning his radio—or was it his old record player—and listening to an old English song. A song she heard him listen to as he bent over the table. An image of loneliness. But the Gunj was full of such people. The leftovers of the Raj. Bablu Paswan is still coming to terms with the loss and the inheritance. The old bed that Potter slept in is still there. A four-poster, an old wooden chest, an old sofa and albums with missing photos where absence is more prominent than presence. Someone came and took a few of these photos from Bablu. A journalist, he recalls.

Potter died at the age of 81. Bablu’s mother used to work at the bungalow. Potter’s father came here in 1958 and bought the bungalow which one can see from the road as one gets into the Gunj. The first one that is a marker of its past. Potter himself was Anglo-Indian as were his parents who were based out of Bangalore. When he saw the advertisement calling Anglo-Indians to set up home here, they moved here. When Potter was old and sick, he would say Bablu was family and when he died, he put in his will that this bungalow be given to Bablu.

Back then, there were parties but over time, things started to change. Potter was left alone with an old song. Nobody remembers the song but they say it was a sad song.

The altar is there along with many other gods that Bablu has placed on a shelf. Like his family portraits that co-exist with the two hats and a photo of Potter. Bablu lost his father when he was young. “Potter was like a father to me,” he says.

Old letters and photos that would crumble if you touch them are what’s left here. Dozens of them. Of families and those remained single. Like Potter who could never express his love. He went to Lucknow to tell her, but couldn’t. She had come to the Gunj in the 1980s and lived in a house her father had bought here. She later left and married someone in Lucknow. Yet another story of unrequited love. Perhaps that’s why the old record player and that haunting song.

Bablu’s chai stall is now shut. The bungalow is in shambles. He now works as a daily wager in the area. Maybe one day, he will repair the bungalow; an act of gratitude.

“Lonely Places, then are the places that are not on international wavelengths, do not know how to carry themselves, are lost when it comes to visitors. They are shy, defensive, curious places; places that do not know how they are supposed to behave.”

—Pico Iyer, Falling Off the Map

Deepak Rana, who is in his eighties and has lived here since 1968, says time, age, sadness, loss, goodness, happiness, and the concept of home are all here. All of these compressed into this landscape that was once conjured as a refuge for those who would seek solace in it. A community that hoped it would set up a homeland within a country. Now, all of it is done with. There are only stories left. In time, they’d be lost too. Where will the Gunj then place itself?

Rana sipped his drink quietly as he always did. Aunty Ruby, his wife, had already retired for the night. The cat was wandering inside the house as usual. Outside, the jungle resumed its dark glory. Acres and acres of Sal trees loomed in the distance. Uncle Rana’s mother had come here in the 1960s for a picnic and stumbled upon an old property and decided to buy it. That’s how it happened. This was a place that was still finding a footing. They weren’t Anglo-Indians but the Gunj seemed like it could be home.

“Why have you come here?” he asked me.

“Perhaps to see before it all vanishes,” I said.

“Why did you come here?” I asked.

“The world lay in front of me. I was young and free. But I needed to lick my wounds,” he said.

There was a pause.

“There is an escape for the restless. Like you and me. This is that place, a headstrong place that refuses to be anything but itself.”

McCluskieganj, a homeland for the Anglo-Indians that never quite became that, is exactly that. A stubborn place that lives on memories of those who first claimed it as home, a refuge for those who have continued to live there like Dennis Meredith and his daughter Karen.

Canteen Majid

Some evenings, Canteen Majid walks along the narrow road to the place where Mrs Kearney is buried along with others. Only he can tell where she lies. The little alcove across the other graveyard has amalgamated with the forest. A small stone marks the grave. Majid, a thin wiry man, is a storyteller. Not all his stories can be verified because there aren’t many who can remember. Who can trust memory if not memory, what else is worth anything in a place like this where many graves have no epitaphs.

Canteen Majid’s father, a daily wage labourer in those days, had come here to work in the coal mines and then found his way to Mrs Kearney who employed him as a housekeeper. She and her husband had taken over the Highland Guest House near the station and she had opened a bakery where she baked bread and cakes that Majid’s father, along with others, would wrap in newspapers and deliver to the houses in the area. Canteen Majid began to write a book about McCluskieganj but in the notebook, the pages are full of stories about a parrot and a king. Is there any Gunj there? He says not yet.

“That’s a tough one to write,” he says.

Majid, the caretaker, now works as a guide. The bungalow where Mrs Kearney lived is now inhabited by his two wives and their many children. The walls have been painted in green. New furniture has replaced the old.

Majid Ansari spends most of his day at the railway station close to his house. That’s where the tea stall was. That’s where the canteen had been set up. That’s where the prefix of his name came from.

In the 1950s, Mr and Mrs Kearney, an Anglo-Indian couple ran the canteen at the station. They had been among the first settlers and after her husband died, Mrs Kearney continued to run the canteen. Then Majid took over but the Railways decided to build a new one and Majid didn’t get the allotment. Business had already declined because the halt time for the trains reduced to two minutes. That’s how the end began.

Majid, the keeper of memories, knows that stories can survive time. That’s why he wants to write a book. After the film crew visited the Gunj, he is hopeful they’d make a film based on his story. But the Gunj is a trap in that sense. Invariably, the stories of the old homeland dream of the Anglo-Indians—the stayers-on—start forming. Like bubbles when you heat up water for a long time.

In time, newcomers like Raj hope that some erasure will happen. They call it the colonial hangover, a convenience of narrative, an indulgence and a reductive rendition of a place so evocative of its past that the future seems like an impossibility. Yet there are settlers like him who insist that the Gunj is no longer the shrine of a homeland for a group of hybrids who held their legacy, the one Independent India had thrown off, the ones who were discards because the British won’t take them along and the Indians thought of them as a reminder of the Raj.

Majid knows that time is running out. It always does in the Gunj.

Like Kitty Texeira whose eyes look like they compress the entire history of the place, the betrayals and the eventual abandonment. The poster child of the Gunj, Kitty’s insistence that this is where she was born and she knows of no other homeland other than this runs counter to those who had designated Britain as home without having experienced it. Kitty was an outsider. To her community that never quite came to terms with her wildness and to the locals, who called her memsahib and never quite took her in although she married an Adivasi man and had three children with him. She had sold fruits at the station ever since she was a teenager to makes ends meet. Kitty represents the counter to all the claims of grandeur here. For her, the Gunj was not an escape. It was home. It still is.

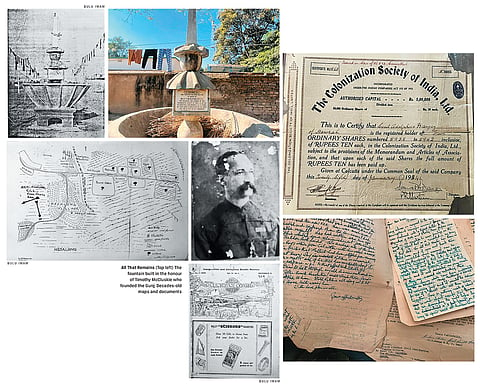

The Gunj is named after its founder, Timothy McCluskie who bought 10,000 acres of land from the Rajah of Ratu and sold the dream of a mooluk to the Anglo-Indian community. The Chota Nagpur hills, with all their gentleness, surround this place. Within this place, there are villages where Adivasis live, weekly markets and many more guest houses now. There are also old English-style cottages, a reminder of what it was envisioned as.

This is an abrupt place, an anomaly too. A site of a political struggle, in terms of making itself a homeland for the Anglo-Indians so their Indianisation could be stopped.

In Collective Memory and Productive Nostalgia: Anglo-Indian Homemaking at McCluskieganj’ Alison Blunt quotes from the memorandum written by Henry Gidney to the Simon Commission where Gidney says that “while the Community is mainly urban, the increasing pressure of Indianisation makes the exploration of fresh avenues of employment necessary, and settlement on the land should provide a ready solution for many who would otherwise be homeless and destitute.”

In the same book, she quotes from a 1934 article in the Colonization Observer that explained the three main aims of McCluskie’s scheme:

“[The aims of] our Community being the only Homeless one in this vast sub-Continent are:

Firstly, colonising with the express object of establishing a Home for itself, secondly, of securing a definite stake in our own Country thereby becoming Indians proper, without losing our identity as Anglo-Indians, and lastly, by getting together, we automatically open up fresh avenues of employment for future generations who will grow up in the Colony, and become practical farmers in due course.”

Another article in the Colonization Observer in 1939 said McCluskieganj sought ‘to build a new Nation and to create a new State’.

“McCluskieganj ‘is not merely to be a Colony, not merely a Home. It is to be the birth-place of a new people, a new race, and a new life which will make India proud of her foster sons and daughters who have been sorely neglected in the past,” it further said.

Nelson ‘Bobby’ Gordon

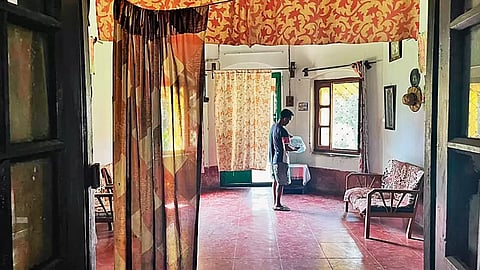

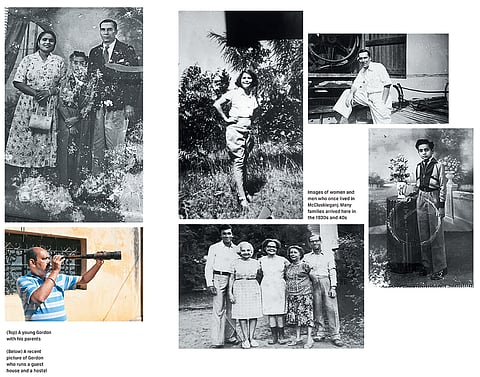

Bobby Gordon came up the hard way. His father Noel used to repair old radios after he retired from his construction job. Gordon is perhaps the only Anglo-Indian in this place of nostalgia to have a good enough present. He insists on his Scottish roots and says he has a son who will carry the Anglo-Indian legacy further. His living room is a testimony to his wealth. A practical man, Gordon says he wasn’t going to carry the ‘nostalgia nonsense’ forever. For him, the future wasn’t going to be a set of stories from the past. A man with mediocre taste whose house resembles modern architecture with some traces of the past for effect, Gordon now runs a guesthouse and a hostel. He married an Adivasi girl who could look after his enterprises unlike an Anglo-Indian who, he says, would “only apply lipstick and host parties”. That’s how legacy works here but not for Gordon. His grandfather purchased this property in 1942. His great grandfather William Perth Gordon came to India from Scotland and was employed with the British Army in Barrackpore and married an Indian woman. His grandfather William Paul Gordon married an Anglo-Indian woman called Nancy. They had a son called Noel Gordon who married a Bengali woman in Ranchi. Then, it was Bobby’s turn and he did what few others had done. A local girl would be a good match for him, he thought. He has some of the old letters and photos which he proudly displays to anyone who asks. Like others, he has stories too like that of Harry Mendies who ran a bus service called Ganga-Jamuna and one would never know when the bus would reach Ranchi. “I never thought of leaving this place. Maybe there is a lot in nothingness too.”

Catherine ‘Kitty’ Texeira

She doesn’t know how we know her but she has gotten used to all the strangeness that strangers bring when they come to find her as if she were an artefact that they must see while they are in the Gunj. A woman who is the signifier of a new nation surging ahead and in the process, alienating those who are outsiders or remnants. Kitty is defiant. Also, she is the antithesis of all that they wanted to claim and preserve. She is almost a feral woman. Frail, agile and delicate. Her spirit stands in contrast to her exterior. It is that of a survivor.

Kitty memsahib doesn’t know where else she could have gone from here. People around her have left. Her mother, Marjorie Roberts was born in Shillong. She was Anglo-Indian and her father was Welsh. She married what they called a “half-caste” who was of Portuguese descent from Goa called Texiera. Kitty was born in 1952. They then moved to the Gunj. The Texieras had invested all their money in the shares in the company that ran the Gunj and lost their land. Marjorie’s husband died and she was left alone with Kitty. They say she wielded a gun and would let nobody come near her daughter. While Marjorie was a typical Anglo-Indian who read English authors like Shakespeare, Kitty could not attend school and had to sell fruits to provide for her mother and herself. Marjorie died in 1988 and Kitty had four children from an Adivasi man who was already married.

Kitty remains the most photographed person appearing on the covers of books and in photographs in articles written about the Gunj. Her children are now grown up. Kitty still lives in the same house. “This is home,” she says. Unlike her mother, who Ian Jack quotes in his story saying that her birthplace was an accident and the world to which she properly belonged lay elsewhere, Kitty entertains no such delusions. She got assimilated as they would say. Kitty doesn’t carry what she calls the nostalgia nonsense.

Andrew Perkins

Up on the little hill, in a house with a portico, a young man lives all alone. There is no road leading up to the house. Whatever there was is left in slight traces, like everything else here. Andrew Perkins has heard of the homeland dream but he doesn’t believe in any of it. He has his own dreams except they have been put on hold for a while ever since he came down here to look after the house so that nobody else takes over possession as has happened in some cases. The house, full of a strange loneliness, is everything he has. His sisters send him an allowance and he lives in this house with green doors waiting for a future that seems far away.

Andrew’s uncles left like many others. His grandfather was one of the early settlers who bought this bungalow in the 1930s. There are many stories about the Perkins. They say his grandmother, an Adivasi, used to work at his grandfather’s house and they fell in love. The grandfather had been married before.

The woman was married off but would come down the hillock in the evenings and walk to the Perkins bungalow. Once, they even injured her leg to stop her from going there but she escaped. When she reached the bungalow, she knew she wasn’t going back.

Like everyone else here, the shared memories are of the potluck lunches and dinners and picnics and those were the glorious days when they still had hope. But Andrew wasn’t born yet. His mother was Adivasi. His father used to work for the mother’s elder sister as a tractor driver in Simdega and his aunt was married to an Anglo-Indian. That’s how he met his mother and they came to stay here.

Perkins inherited a dream. It was almost an imposition. “The only thing left is this house,” he says.

“People come here to look for what McCluskieganj is also looking for. Everything has vanished,” he says.

Perhaps he will write about the “good old days” just to preserve some of that past that he didn’t witness. The nights cut him off. After 5 pm, he doesn’t go out. It is dark.

Dennis Meredith

Everyone will tell you in the Gunj that Dennis doesn’t like to talk, that he lives in the past with motors and machines that date back to the 1960s, and after people left, he became a recluse.

On the road that leads to the railway crossing, a small sign says Hermitage. You take the lane and a small gate appears on the left. A dog barks in the distance and tall trees that have creepers hanging like curtains, shield the view.

“You spoke in English. Like a lady. How could I refuse?” Dennis says, leading the way through a garden that hasn’t been tended to in a long while. His mother was an Adivasi and his father moved here after his retirement from the iron ore mines in Jharkhand. His father bought two houses on 8.36 acres of land. “It was only Rs 7,500,” he says. Dennis was the only son and when his father died, he returned to the Gunj after working in Asansol.

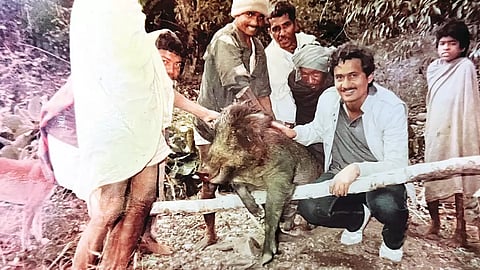

Over the years, he witnessed the collapse of the place. Time is what you have here. You have the time to remember. Like the man who was the village alcoholic who died in the coffin where he had begun to sleep in his last days. Like Harry Mendies who wrote the receipt of the sale of his property on a piece of paper with the lead from the bullet while on a hunt.

This is McCluskieganj—Little England or Mini London, 1,500 feet above sea level, 70 kilometers from Ranchi, the capital of Jharkhand.

The settlement had attracted 250 Anglo-Indian families by 1939. In all of this, there was also the desire to free themselves of British patronage. Anglican bungalows with flower gardens and slanting tiled roofs were built. Two churches came up. A club, a post office and an abattoir followed. Trains lugged their heavy wooden chests and other furniture. Lace and breeches were sold here. Cake and wine, too. For a while, it seemed like it would last.

But people left and now, only a handful of Anglo-Indians remain here. By 1955, the Colonisation Society packed up and the Gunj became a place for retired people. After the exodus, outsiders came in. Bengalis first. And then came the others. They came for the exotica the Gunj promised. A guesthouse owner said the Gunj is also theirs but everyone suffers from a colonial hangover.

In this idiosyncratic place, even this history is contested with people’s imagination. About the genesis of its name, one story goes as such. There was an Anglo-Indian man called Mac and he fell in love with a girl called Luskie here and their love met with a tragic fate and both killed themselves. That’s how this place in Lapra came to be called McCluskieganj.

There was a woman called Dorothy Thipthorpe who made jams and wine, and in those days, they say the market was better than what Ranchi had to offer. China silk, cigarettes, cakes and everything else was sold here. There were dances and parties and a lot of cheer. The first phase of the exodus saw a lot of people move out. By 1997, out of 400 Anglo-Indian families, only 12 were left. Some efforts were made to revive the place but nothing happened. Yet the Merediths, the Jennings, the D’Rozarios, the Barretts, the Hourigans, the Perkins, the D’Costas or the Mendies haven’t abandoned all hope. It is the burial ground that holds the history and the secrets of this little town. There is no money to fix it and some graves are unmarked and only in the epitaphs of the old graves can one read some of the names. Nobody knows about some of them here anymore.

People still come here to find their lost homes. It remains a forgotten town which finds a mention in some of the stories of Bengali writer Buddhadeb Guha who once owned a bungalow here, and in a film called A Death in The Gunj made by Konkana Sen Sharma who spent time here in her childhood.

After the second exodus when the Naxals camped here, a lot changed. Still, the road goes through a forest and they say the ghosts keep a watch. The ghosts of those whose homeland this was. By the 1980s, it was a ghost town after the Maoists took control. When dusk falls, people retreat. Only the animals venture out.

Whats Lies Ahead?

In 2019, a Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha by Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad who said there were only 296 members in the Anglo-Indian community as per the 2011 Census. This has been contested by Anglo-Indian bodies. Between 1952 and 2020, two seats had been reserved in the Lok Sabha for members of the Anglo-Indian community. In January 2020, the Anglo-Indian reserved seats in the Parliament and State Legislatures of India were abolished by the 104th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2019. In this issue, Outlook looks at what lies ahead for this small but fascinating community of Anglo-Indians left in the country.

Chinki Sinha in McCluskieganj