It would have been a bone-dry summer afternoon—all I remember is the glare bouncing back off the asphalt, as it always did. The usual Delhi slow torture. Nothing to suggest a dasha sandhi. Perhaps little steam mirages rose from those baking streets, as they wove little Lutyens patterns around old qilas, precluding a clear line of sight into the future. Then, suddenly, the relative cool offered by bamboo mats strung along a hotel verandah, and a room on the right. Sitting at the far end was Vinod Mehta, very much the rancher looking to hire some cowpokes.

Image Musings Text

What does a magazine do when the coherent world of letters shatters around us? Open ourselves up to the beautiful cacophony.

Outlook was yet to be born. A kind of pre-natal hush hung in that room, but nothing was moving just then. That air of leisure, it turned out, would endure. On one of my pre-hiring visits, Vinod Mehta was seated with a cache of old, soiled notes spread out on his table, with sticky tape! That sight should have been enough forewarning! As part of his Seventies SoBo eccentricities, he had also evidently acquired the Parsi virtue of parsimony. Hard, but fruitless bargaining ensued—and I was in for the long ride.

Vinod loading his magazine, so to speak, for one more shot at journalistic gold was quite an event back in 1995. Over the next few months and years, there was to be a sort of velvet revolution in the magazine space. Nothing of the jokey, avuncular figure people saw later on television could paint the man as he really was. The legendary Editor-as-Dictator, he could look clean through you, especially if you were asking for something he wasn’t overly predisposed to giving. Crusty and imperious, but allowing flashes of paternal affection to show through. A man of endearing, and infuriating, caprices. And a cultivated, Olympian distance that would look seriously anachronistic now.

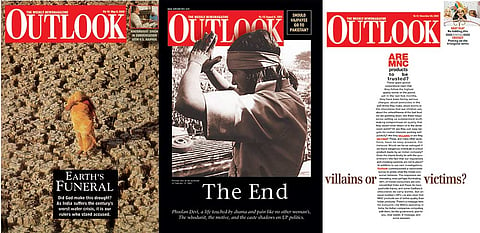

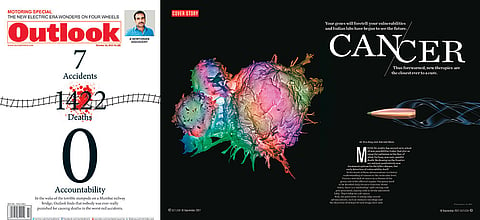

The old convention for dating a generation among demographers seems to favour nineteen years. Outlook is now old enough to count using the vigesimal system, in twenties—like the old rancher counting cattle head. It’s two-and-twenty right now. With a little allowance for the alarmingly faster maturation cusps for the millennials, that means we’re well into the second generation. What has changed in between? From the day Outlook ran its first cover—breaking a long-held media taboo, speaking of Kashmir’s desire for azadi (with my first headline here, Till Freedom Come)—to this autumn, when Steve Coll delivered the first Vinod Mehta Memorial lecture?

It seems a bit unreal. A few easy markers first. Boris Yeltsin still ruled Russia. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was still laying waste to Kabul. Till a season or so ago, Kapil Dev and Manoj Prabhakar were still bowling for India. Mohammed Azharuddin, far and away my favourite cricketer (give or take a couple), was still captain, as yet untarnished by the betting scam Outlook broke a few years later. Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra were still listed as heroes—indeed, the latter had just given a kitsch-comic-grindcore hit that was to give its name to another magazine that partly came out of the Outlook womb, one with more radical affectations. Nirvana’s suicidal frontman Kurt Cobain had just “gone and joined that stupid club”, as his mother called rock-n-rollers who died young.

Back home, rather more epochal changes were under way. The Nehruvian consensus was gasping for breath. The Rao years were winding down, but the inscrutable Brahmin, who was in a way the old building and the wrecking ball rolled into one, had done his job by then. Politics had begun fragmenting along new lines. Those fracture-lines have not healed.

The old elite were not quite in retreat. Sonia Gandhi’s first coming-out public rally graced the cover of one of our three pre-launch trial issues—Sitaram Kesri, who was born in the year of the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre, was still in the game and had to be ousted. The infamous tea party hosted by Subramanian Swamy for Sonia Gandhi and Jayalalitha against the BJP (yes, that’s what he was up to those days)—exactly around the time Gen Musharraf’s irregulars were homing down on the Kargil heights—was still four years away.

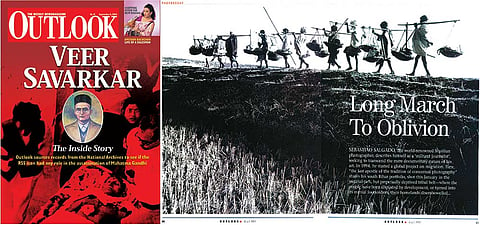

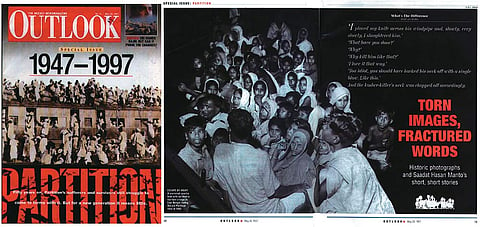

In between, the news magazine added a bit of harmonic richness to its palette. Its first special issue, on the Partition’s fiftieth anniversary, brought in literature, archival visuals, and an essay format that we continue even now—an integral space of text and image within which to tackle history, memory, analysis, prognosis.

That format, and the repertoire it produced, kept growing even as the cantankerous news world kept interrupting the calm. The nuclear bomb, the almost-peace of Lahore, the almost-war of Kargil…we blundered through it all like Amos Gitai’s benumbed soldiers in Kippur. Another special issue: a futuristic one for the turn of the millennium, and then off for our customary year-end holidays. And as always, aborting it for some more breaking news: the Kandahar hijack. And then off to spend the last dusk of the millennium on the banks of Assi Ghat, staring into the river. And the next dawn in the mists of Sarnath. Suspended between the age of leisure and the coming world of 24/7 adrenalia.

Everyone’s an Anchor

So what changes, and what endures? Each infuses the other with its quality: change itself is constant. Back in 1995, it was customary to define things as located in transitional times. The magazine itself must have seemed a curio from an old-world, genteel universe at a time satellite television was opening up. In those days, print had to survive some intense self-doubt—and defining oneself in contradistinction to TV was the name of the game. You needed hot exclusives—news breaks from Kargil, to cricket betting, to highway scams. You needed a sense of fun, and wordplay for the sake of it (I own the dubious privilege of having coined ‘KJo’ on these pages—no thanks to JLo—and if no one else comes forward, am also staking claim to the patent for ‘Cyberabad’, which went from a headline to a real addition to Indian geography!) But beyond all that, one also needs a kind of longue duree lens, a space for reflection.

Now, with the media feeding frenzy of recent times, that dual need has only intensified. Just like a complex economy like India can simultaneously contain everything from pastoral nomadism to digital natives, our media now has everyone from community pamphleteers, radio jockeys, TV anchors screaming blue murder, old-style print savants, Facebook warriors, Twitterati and ghost-trolls all in the game at once. In what way can this Babel resemble any idea of public discourse? Can it at all? How to make sense of it?

Well, it’s clear that if any domain of human activity describes this present age, it’s the media. It no longer merely conveys reality to us like a reliable messenger. It surrounds us, it consumes us, it constructs a parallel reality within which we are all constrained to live. It’s the mediatic turn. Never before has McLuhan’s seemingly nihilistic axiom—“the medium is the message”—rung so true. How does one think about traditional print media in this context? Is it enough to talk of journalistic “values”, of taking for granted a whole way of doing things—a certain reliability and solidity? To say you can’t rely even on the images you see, that seeing is no longer believing, that everything else is post-truth and it’s print that brings sanity to the world?

Perhaps such fundamental qualitative changes in human experience as we see now can only be measured post-facto. We are living through a sort of prolonged explosion that’s changing the order of things. It’s not just about a change of medium. The media also expanded its footprint dramatically, and began speaking directly to a lot more people. And assumed a new kind of power. But no gulf separates the producer and consumer now—each one of us is both. Power also got broken.

The old print culture was driven by literacy, which was also elitist in a country like ours. Something essential about the grammar of communication has changed. When TV happened, people felt it was a return at long last to the regime of orality—the means through which our traditional intellectual commons circulated. Now, after that cantankerous detour, is it back to textuality with online media? Or is it something more composite, a network of channels feeding and feeding off each other? A self-consuming, self-producing manyness?

Perhaps the familiar brick and mortar of print helps us find our way through the shooting neon, navigate the rapids, to an extent. In the strict sense of truth-making, though, it’s difficult to insist print is the sole repository of journalistic wisdom: on numerous occasions, it’s the new energies of social media that broke the omerta when traditional media pulled its punches.

It won’t suffice to complain about the media cacophony around us, for a new, active, dynamic “public” is being constituted, thinking about its own circumstances, speaking to itself and, through this exercise, bringing into its fold more and more voices. A collective mental life swims into view. In this openness, print learns from new media even as it transmits its virtues to it.

The Outlook Party

Vinod no longer stalks these corridors, but a lot of him has passed on to the magazine. Style, irreverence, savoir faire, a capacity for high polemic and cool analysis alike, a willingness to voice heterodox opinions, to say your piece regardless of received wisdom. With him, it was a happy, signature blend of those traits. Maybe a lot of it drew upon a pre-existing blueprint—and in turn refined and bequeathed those elements to our common idea of a magazine space. Even to a larger common pool of virtues and vices.

Look at even his style as a diarist/writer: witty, personal, confessional, self-deprecating, non-reverential, willing to call out humbug in high places. Judge those traits against the ivory-tower savants of old and then against what’s ubiquitous now all over social media, and one may find a high degree of genetic match with the latter (minus the self-deprecating bit). It’s too sad that only parody accounts like @DrunkVinodMehta lived on: for, in an essential way, the real one pretty much anticipated FB and Twitter (and offline, could have handled a troll or two!).

Mama, Look at Me

Trace the changes from the old standard of journalism—the dull, impersonal style of ‘objectivity’ with no ‘voice’. Even bylines were a hard-earned privilege in newspapers till the early ’90s. Then ‘voice’ became de rigueur: the reader needed to connect with a real person. Then the genie slipped out of the bottle and ‘voice’ got democratised via blogs. Authority, which spoke in reserved tones, was now scattered, fragmented. Truth became a many-fangled thing. Being opinionated became the sine qua non—the quality of internal rigour, of ombudsmanship, getting diluted was a byproduct.

Television moved through the same arc. From a time when anchors sat ramrod-straight and spoke in dulcet Metro announcer tones to when they started nodding to the co-anchor’s words, started pacing around, started walking towards you threateningly, delivering news with a variety of bowling actions (off-spin seems to be the favourite). It was natural (and easy) for TV to get personalised. For flesh-and-blood people to be, well, flesh and blood—too much of the latter eventually, as it turned out.

But the desire to be heard above the bazaar din soon got the better of old printwallahs too. You could hear the printed fonts scream at the passing eye, like Janpath salesboys. Style, tone, content…all saying: look at me! If on FB and Twitter you have to be more outré and snarky and overstated to be heard, the introspective grace of old print wasn’t going to work either. Headlines, of course, were the first to start screaming. Or laughing. Or being outrageous. Anything to arrest the saccadic movement of the reader’s eye.

One can offer a high-minded treatise on the headline as separate sub-genre of linguistic expression. But it’s better to confess to being an early culprit, and occasionally an egregious violator. ‘Sachin Endulkar?’ went the headline for a 2004 story we did that speculated on his future. Well, I’m making my grouse public. The Times of India stole my headline a couple of years later, and Sachin read that one…and gave a statement that it made him sad! To be denied the dubious pleasure of being acknowledged as the real sadist is what is really sad. Anyway, you read that here first.

But snark is now a universal vice, and copyrights mean nothing in the world of creative commons. Now everyone swims together in the turbulent waters of Twitter. Even the old high-caste print gurus, with the caveat that their old ivory-tower hauteur is denied to them. Most vestiges of the old authority have crumbled. Whether the eager newbie or the editor who spoke from on high twenty years ago, they all stand the risk of copping abuse by the tonne. Especially if they have a strong opinion. Tweeting, for the stars of that firmament, is akin to taking an occasional sniper shot and ducking out of the way before the barrage of toxic buckshot comes your way.

There’s an inherent reflexivity to how forms of media co-create a public culture. Now all of them coexist—no, that’s too inert a word. They cohabit. And without even being aware of it, leave alone acknowledging it, everyone influences everyone else. Online debates anyway have a peculiar habit: because they are conducted in public, and one’s personal prestige is challenged in front of everyone, very few voices admit defeat and revise their opinion.

But that personal intransigence masks the real interchange of opinions in this melting-pot. Witness any FB debate. Even the latest one that broke even as we were readying for press: after one round of #MeToo solidarity, and countless stories of having been personally subjected to sexual abuse, some plucky women compiled a list of “predatory males” in academia, drawn from anonymous victim testimonies. Countless women (and men) shared the post, more names were added, and all possible viewpoints on gendered violence were aired angrily.

There were those in open solidarity, those with doubts, those who negated, those with an attitude of denial. Many voices (mostly men) said this was tantamount to a witch-hunt, and the technique of mob lynching heightens the chance of the wrong man being strung up on the nearest tree. Feminists of an older stock assented to that, saying a cult of naming and shaming is not the best form of justice delivery and due process and evidentiary value are key. And even the best feminist names who appended their name to that came in for a fresh round of excoriating critique from the younger radicals who insisted on the value of breaking the culture of silence.

Vinod Mehta and Editor

How do you replicate this sheer range, this cornucopia of perspectives, in a print magazine? The extent and quality of dissent possible is perhaps extinguished here—(“if you disagree, you are a rape apologist”)—but that’s not the point. It would be wrong to look for consensus online: the very fragmentation, the irruption of new voices is what social media has brought before us. Left establishment voices, for instance, are irritated by the flame-throwing words of Dalit radicals—but pray, where do you find Dalit voices in the ‘mainstream’? Where else do you find them except social media? In contexts marked by accumulated injustice, like gender or caste, dissensus itself is a virtue.

It’s a good thing if the old gate-keepers of knowledge are challenged. It’s when they crumble together that you notice how the words ‘author’ and ‘authority’ are so linked—that you realise arrogating to the self the onus of being the normative centre is passé. As is the inherently anti-democratic idea of invoking a founding father for truth. I, for one, believe print—that integral space of text and image, and its unique way of composed, reflective, methodical truth-finding—will adapt and endure. But with no implicit sense of hierarchy. The man who named his dog after his lifelong designation—feudal in manner, orchestra conductor by working style, and a beatnik at heart—wouldn’t have minded.

Sunil Menon is deputy managing editor of Outlook