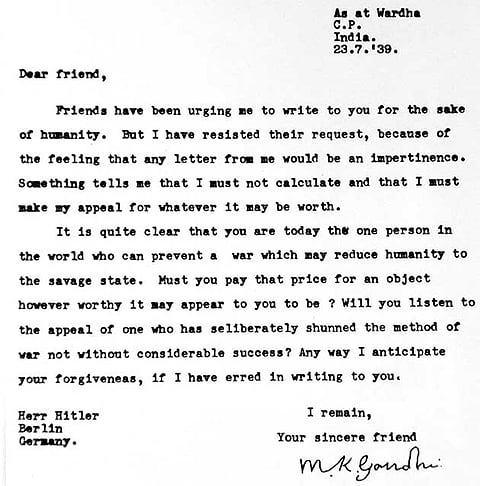

In the service of Pujya Pitaji,

Gandhi@150: A Son’s Jeremiad

Harilal Gandhi defied his father. This is his anguished J’Accuse.

A worm enters the body of a wasp and flies away having assumed the form of the wasp. I believe something similar happened to me. I have received much from you, I have learnt much, I was formed by you and my character emerged unblemished. The only difference is that I lacked the patience and endurance of a worm and ran away even before I could become a wasp.

I separated from you with your consent. In so doing I followed the dictates of my conscience. This too I learnt from you. It is usually not possible to distinguish the Phoenix Institution from you and hence I left that too. We spoke much. You said much; you also did all that you could. I also said all that was possible for me to say. It was destined that we be separated.

When I experienced the desire to write to you at length, the following thoughts came to my mind. “Your life has been a public one. Even your personal life is no secret. All are naturally curious to know more about your life. Many would have asked you questions about the sudden change in me. I have been unable to say all that I wished to say to you.” For such reasons I considered it proper to write a public letter to you.

The thoughts expressed in this letter are my own. Our differences are not of recent origin. We have had differences for the past ten years. They stem from one subject. You are convinced that you have given me and my brothers necessary education. You are convinced that you could not have given us a better education than what you did give us. In other words, you have given us necessary and sufficient attention. I believe that with your preoccupations and engagements you have unintentionally paid us no attention at all. It affected me and that is what I shall describe in this letter. I believe that due to your overwhelming desire to provide us education and care, you have experienced the illusion of having done so.

For ten years now I have been crying and pleading with you. But, for the wasp, the worm is insignificant. That is, you have never considered my sentiments. I believe that you have always used us as weapons. ‘Us’ in this context means me and my brothers—Manilal, Ramdas and Devdas. I believe that to a lesser or a greater degree your conduct towards us brothers has been similar. You have dealt with us just as a ringmaster in a circus treats animals in his charge. The ringmaster may believe that he is ridding the animals of their beasty character because he has the welfare of animals in his heart.

If you have no knowledge of our sentiments, then there is no possibility of you paying any heed to what we have to say to you. You have oppressed us in a civilised way. You have never encouraged us in any way. The environment around you has become such that even a person who differs from you innocently and conscientiously is as good as dead. You have spoken to us not in love but always with anger. Whenever we tried to put across our views on any subject to you and engaged in a debate with you, with your permission, you have lost your temper quickly and told us, “You are stupid, you are in a fallen state, you lack comprehension. You think that you have attained the zenith of knowledge. You argue against me in everything. You will not know what is good. Such is your samskar.” By saying such things you have shown your disdain and oppressed us. Thus oppressed I have remained melancholic, anxious and, as a result, sick. You have instilled fear in us, of you, even while we are walking, ambling, eating or drinking, sleeping or sitting, reading or writing, and working. Your heart is like vajra. Your love... I have never seen; so what can I say about it?

Under such circumstances what can people expect from your sons? Naturally they are disappointed. As you yourself said, after his first meeting with us, Poet Shri Rabindranath Tagore used the term ‘ignoramus’ to describe us. You also said that later he changed his opinion. It must be said, despite all the reverence I have for him, that he was being kind and generous. I remember one of the Phoenix inmates reporting that even Professor Gokhale had told you that our affection for you arose from fear. It is not as if I am drawing your attention to this for the first time. I have been pointing this out for years.

Whenever someone asks you about our education you reply that we study what our samskar allows us to. Forgive me Pitaji, but it is not only our samskar which is to be blamed for the state of our education.

As your political life became full of hardships you have changed your ideas, and along with that you have also twisted our lives. I believe without any hesitation that our lives hitherto have been irregular and uncertain. You went from here to South Africa, came back, went again and came back once more. What we learnt here we forgot there. We learnt one thing for six months, something else for another six months and a third thing for another six months. Naturally, nothing came of it. We might be foolish; but allow me to add that you have kept us foolish. You have never considered our rights.

Here, I am reminded of the story of a father and his four sons. The father felt that he should initiate the sons in some profession. He called each one and gave them the necessary encouragement. Each one was shown a path that suited his capabilities. What the father identified as the right path for one, he dismissed as the wrong choice for the others.

He called the first son (the father knew that this son desired knowledge) and told him, “Son, now you have reached an age where you should think for yourself and of your future. It is my advise that you should study further. Remember the shloka, ‘Vidya nama narasya rupam adhika...vidya-vihina pasu.’ People will revere you if you become knowledgeable. Only the wealth of knowledge stays with us, all the rest is false.

“Do not even think of business. You must have heard how many have become bankrupt and died in bankruptcy like Chunilal Sarriya. A businessman is worried all day long. He cannot even sleep with ease.

Moreover, those who accumulate a lot of wealth endanger their lives. We have read about the son of a wealthy man in America who had to live in a golden cage because the father was afraid that his heir might be killed.

“Do not even think of agriculture. If you were a farmer and it does not rain for two years, you would have to bear huge losses. Government taxes would push you into debt. You, your labourers, your oxen—all would suffer. If you work with oxen your intelligence would also become like theirs.

“You might have thought of service, but you know that among us service is considered most inferior among professions. One has to spend a lifetime converting fifty rupees into fifty-one rupees. Moreover, you will always have to be subservient.

“Therefore, my son, don’t think of doing business, or agriculture, or taking up a service even in your dreams.”

Then he called the second son (this son had the qualities of a business¬man). Here, the father praised business and decried the pursuit of knowledge, “My son, I see the qualities of a Bania trader in you. I would be happy if you enter into some trade. There is immense wealth to be earned. You would also be famous. Remember the shloka by Bhartrhari, ‘Yasyasti vitta sa nara kulina sa pandita...sarveguna kancanam asrayanti.’ Look at Premchand Raychand! He built Rajabai Tower and his name is immortal.

“If you are considering further studies, read MA. Banake Kyui meri Mim Kharab ki? Don’t you see destitute BAs? Who is willing to pay them even thirty rupees? To be educated means to be debauched. Therefore choose trade and commerce.” (He denigrates agriculture and service.)

He called the third son (the father knew that this son wanted to be a farmer) and told him, “Son, you have improved the condition of our farm. I went there earlier today. I think you are fond of agriculture. I am willing to buy you more land. Moreover, there is a saying among us that farming is the most superior of all occupations, after which comes trade, and service is the lowliest of all professions. And how simple is the life of a farmer? Have you ever heard of a farmer falling sick? His body is as strong as iron. No one prays to god as much as a farmer does. You select the land and we shall buy it.” (As before, he denigrates the other occupations.)

Finally, the father called the fourth son. (He knew that this son liked administrative service. He presents the lowliest of professions as the most superior.) “Son, it would be good if you visit our ruler. He will give you a suitable position. Our forefathers have been administrators of this state. How can we give up our claims on it? You must have heard that one of our ancestors was a Divan. That grandeur will not come back to us without state service. We were the rulers. Son, I would like you to bring back the glory of our forefathers.” (He denigrates other occupations.)

Pitaji, you have not paid any attention to us even when we sought it. God grants a newborn child mother’s milk. If the child is given any other food, it has indigestion and falls incurably ill.

It is necessary to narrate my life story in support of what I have said earlier. The period to which I refer is from 1906 to 1911. In the end I ran away from you in 1911. This is the second time that a similar incident has taken place.

In 1906, at the age of nineteen, I implored and beseeched you, I made innumerable arguments and pleaded that I should be allowed to chart the course of my life. I wanted to study, to gain knowledge; I had no other desire. I demanded that I should be sent to England. I wept and wandered aimlessly for a year but you paid no heed. You told me that character building should precede everything else. I had respectfully submitted to you that a tree once fully grown cannot be bent in another direction. My character cannot be altered now. You would remember that you had gone to England at the age of nineteen against the wishes of all. Today you consider the lawyer’s profession sinful! It is doubtful that you would be able to do what you do if you were not a barrister.

Today, I do not consider my character altered. I do not think even others would claim that my character has been altered. The mistakes that I committed then, knowing them to be mistakes, were due to my weakness and I was helpless about preventing them. I cannot be held responsible for the mistakes that I did not consider to be errors and those which I did not commit. With time, having learnt and understood some things, I do not repeat the mistakes of childhood. Therefore, some may very well say that my character has altered.

In order that my character be formed, using many arguments you proved that I was incapable of studying and that I first needed to acquire that capability. You made me adopt, not in Athens, but in today’s world, in Johannesburg, the paths of Plato, Xenothon and Demosthenes—not with the guidance of any teacher but on my own. You asked me to drink milk not in the house of a cowherd, but in a pub. I am sorry that I am no Plato. It was proved that though I wanted to study I was incapable of it. All saw me with condescending eyes. You proved that I was utterly foolish. I had to accept your verdict.

I was told that I should leave Johannesburg and live in Phoenix to build my character. The Indian Opinion is published from Phoenix. Phoenix is regarded as a place for those desiring a simple life. No one can question the objectives of Phoenix. The value of nectar cannot be measured. But who got it? Who drank it? Allow me to remind you that Phoenix caused a dear friend of yours and an excellent electrician like Mr. Kitchin to run away. Phoenix also forced a gentleman and an excellent engineer like Mr. Liens to run away. There might have been other reasons in case of Mr. Cordes, but one particular reason was sufficient to drive him away. I can give other similar names. You believed (despite our warnings to the contrary) for many years that Murabbi Bhai Shri Chhaganlal would not leave Phoenix so long as even one tile of its roof held. You are aware that this belief has been proven false.

For the sake of Phoenix’s future you decided to send Murabbi Bhai Shri Chhaganlal, as someone who had the finest understanding of the objectives of the Phoenix, to England in 1910 (this despite the fact that Dr. Mehta Saheb had requested you to send one of us to England at his expense). He fell ill there and returned to India in six months. You are aware that he decried Phoenix and praised the Servants of India Society. I was asked to build my character in a place like that. But who was I there? Was I of any consequence there?

So be it. But, the plight of my mother was much worse than mine at Phoenix. I saw that she was being insulted often. What I saw was like witnessing a thief admonishing the sentry. People brought complaints to you: “Mrs. Gandhi consumes too much sugar and hence expenditure has gone up.” “What right does Mrs. Gandhi have to assign work to a worker of the press?” People said that Harilal does this and Harilal does that. If you had maintained records of all the complaints it would certainly fill a small notebook.

We would have preferred to be caned rather than be admonished by you everytime a complaint was made. It is beyond my capacity to describe the hardships that my mother had to undergo. All this I could not bear. If we ever brought complaints to you, your response would be, “He is a good man. He desires your welfare. And such and such is a jolly fellow.”

It was then the idea that you were using us as weapons took root in my mind. In 1907 the satyagraha commenced. I joined the struggle. I had the opportunity to think freely while in jail. When I was out of prison I shared with you my ideas about how and what education we could acquire. But you deprecated my thoughts. I remained oppressed. I considered myself a lost cause. I stopped expressing my views.

Finally, after pleading with you for five years, in accordance with your teaching I obeyed my conscience and ran away after writing a personal letter to you. I thought that I would go back to India. That I would earn my livelihood and stay away from relatives and their temptations. I thought that I would live in Lahore. That I would study and manage to feed myself somehow. From Johannesburg I went to Delagoa Bay on my way to India. I requested the British Counsel there to send me back to India as a poor Indian immigrant.

I was delayed at Delagoa Bay, you came to know of my whereabouts and you caught up with me. Obeying your orders I returned. I remained steadfast in my views. Therefore, instead of giving me a patient hearing you mutilated my thoughts and clipped my wings. You made me give up the idea of going to Lahore and instead made me stay in Ahmedabad. You promised to give me thirty rupees for monthly expenditure. You did not allow me to measure my capabilities; you measured them for me.

I stayed in Ahmedabad obeying your wishes. But my original objections were proved correct—relatives and social obligations to the family surrounded me. There were deaths in the family. After the death of my uncles I took ill. Only those who nursed me and the doctors of Ahmedabad could possibly give you an idea of my illness. In 1912 I failed the matriculation examination. How long could your daughter-in-law have stayed in her natal home? I was worried about this.

How could all the expenses be met in thirty rupees? I incurred debt. You say that mothers ornaments and those of your daughter-in- law should be sold and thus the debt be repaid. At the same time it is quite understandable that your present circumstances do not allow you to give money.

Despite leading an unhappy life in Ahmedabad I do believe that I learnt much, I experienced much.

Now you have returned to India. I spent some days with you. My effort to rejoin the Phoenix Institution has failed. My views remain unchanged. You remain steadfast in the choice of your path and consider it to be just. When I complained to you that you did not allow me to go to Lahore and asked me to stay in Ahmedabad, you responded by saying, “Why did you not remain firm in your views then?”

Now I am firm in my views and will remain so. If I were to die doing so, I shall die a satisfied man. I know that my conscience is free of sin.

Under the circumstances that I have narrated, and with my wings clipped, I recommenced studies after seven years. I failed the matriculation examination for three years. I am not worried on that account. I consider it a sign of weakness to give up studies now. I will earn my livelihood, get through my education and become a servant of the country. Our differences on knowledge of letters are not new.

I consider it useful to study the subjects that are taught in our universities. I am aware that in the recent past the government universities have discarded some important subjects. The changes in the methods of imparting education are acceptable to me. I consider examinations to be important. I consider the awarding of degrees to be a form of encouragement to students. I see nothing wrong with schooling. Some reforms are required everywhere. I have no wish to claim credit by pointing them out. For me, even students living in a gurukul constitutes schooling.

You dismissed my desire to be a barrister by saying that it was a ‘sinful activity’, but you sent Bhai Sorabji to England for the very same purpose? This contradiction sows the seeds of the thought that you love us less. Bhai Sorabji is a good man. But, you would have tried to please even an ant at our expense.

Even after hearing and reading all this you would say only one thing, and that I know: “I have always loved my sons to the extent that I have not allowed them to do anything that I have considered wrong.” Pitaji, the facts given above contain my response to your justification. One more thing remains to be said here. It is so subtle and delicate that it cannot be said fully, nor can it be expressed through words. Nevertheless, I consider it my duty to write about it.

You admonish me that I married ‘against your wishes’. I accept that. Given my circumstances I feel that my action should be pardoned. I believe that no one could have acted differently under those conditions.

You know that I got engaged while I was still a child. This was arranged by Pujya Kala kaka in your absence. Thereafter at the age of seventeen I came to Rajkot severely ill. On hearing that I was on my deathbed you had written a letter of solace from South Africa. At that time I was staying with Murabbi Goki phoi. There were no men in her house. Haridasbhai took me to his house. I was nursed and cared for in his house. I recovered my health. I stayed in his house for about two months.

I was not entirely unaware of the situation at that time. Haridasbhai’s family was considered reformist. I knew that I was at my in-laws’ place. Naturally, I desired to see what kind of girl was destined for me. I saw a photograph. A thought entered my mind that I was not engaged to an unsuitable girl, and that the in-laws’ family is also good. After some days I desired to see the girl face to face. I saw her. Time did the rest. As we got more opportunities we talked and joked. The bond of love linked us.

After regaining my health fully I returned to our house. How were we to meet after that? We exchanged letters. Our affection for each other grew. It was time for me to leave for South Africa. What was I to do? It would be five or more years before I could return from South Africa. In Hindu society a girl who remains unmarried after a certain age is subjected to criticism. We decided to get married. I have the letter of 1915, which proves our reasons for the marriage. I am not reproducing the letter here. But I am willing to produce it whenever asked.

We got married in May 1906. Three months after our marriage I left India to be with you. Please allow me to state that ever since the marriage, we have remained subject to your wishes. We have been married for nine years. We have spent six of those years pining for each other.

I dissociated myself from the Phoenix Institution which is now in Bolpur because I witnessed hypocrisy there. I consider the objectives of Phoenix to be most superior; but with respect to what I have seen, you are the only one who leads his life according to those objectives. It is my view that no one else is capable of following them. We all consider the ascetic life to be the most superior way of life, but all of us still lead the lives of house-holders—a practice which is inferior to the ascetic life.

No one can be made an ascetic. No one becomes an ascetic because others ask him to. A person becomes an ascetic on his own volition; only such asceticism can be and is sustained. If I recall correctly, during the time of Cromwell there was a group of puritans. In those days reform was in the air. Those who did not join the puritans were considered inferior to them. Many were shamed into joining the puritans. When the winds changed direction it resulted in a ‘puritan reaction’. People withdrew from it with the same enthusiasm with which they had joined it. It is my humble belief that the same is true for the Phoenix Institution. The norms of the Phoenix Institution are the finest; but I am not willing to accept that those who stay in it follow the Phoenix path on their own volition.

At present, the Phoenix Institution has twenty-one members, young and old. Six of them have joined recently. Therefore, I am not counting them in. Of the remaining fifteen, I have known fourteen for many years. Phoenix was established six years ago. With affection for my younger brothers and respect for Murabbi Bhai, I must state that in these six years of following the ideals established by you and given their efforts, the change in them is not as much as it ought to have been. The apparent change is due to time—a man with an angry disposition does not remain the same after six years. It is extremely difficult to imbibe virtues of high morality. There should be no ill will for the Phoenix Institution. But, ill will towards the institution is quite apparent.

I cannot believe a salt-free diet or abstinence from ghee or milk indicates strength of character and morality. If one decides to refrain from consuming such foods as a result of thoughtful consideration, the abstinence could be beneficial. It is seen that such abstinence and asceticism is possible only after one has attained a certain state. By insisting on salt-free diet and on specific abstinences, at the Phoenix institution, you are trying to cultivate self-denial. It is my belief that before self-denial certain other qualities—non-possesion, courage and simplicity—have to be cultivated. I am skeptical whether those who are devoid of such qualities, but eat salt-free food or are fruitarians for the benefits offered by such diets, should be considered self-denying. Those who consume a salt-free diet because of such motives cannot be considered self- denying, as they have no ascetic qualities. Such persons promote hypocrisy by eating salt-free food. They think they have attained self-denial. They believe that godliness is manifest in them. They consider themselves superior, if not to everyone, at least to those who do not avoid consuming salt. It is well-recognised that among the Hindu families thousands of women and men observe rigorous vrata round the year. They observe fasts, but barring a few exceptions, they possess no sterling virtues; and good character is found also among those who do not observe any vrata.

‘You have never seen the person in us’.

After observing vrata, our women and men eat the usual roti and dal in large quantities; instead, if they were to follow a diet of fruits their vrata would certainly bear results. Those whose digestion is good keep good health. It is not as if the vrata observed by those who eat roti and dal does not bear results. Because, we know of many who eat roti and dal and yet observe the strictest of vows in the Jain Upashrayas. I wish to state that after the vrata people tend to overeat. It is my experience that even the self-denying are not exempt from this. If my own experience or experiment of being a fruitarian for only twenty days has any validity, I speak with experience—I have also observed this characteristic among those who were fruitarians for six months—that people eat fruits and nuts far in excess to even those who overeat roti and dal. Therefore, indigestion is bound to happen. Under such circumstances I see no benefits in adopting a fruit diet.

It is my opinion that one should get accustomed to eating less food and only thereafter consider becoming a fruitarian. Eating less means being indifferent towards food and practising abstinence. Then, issues of “I will not be able to give up this and that” do not arise. Only after attaining such a state do questions of what one should eat and what one should abstain from appear meaningful and beneficial. We are usually conscious of what we should eat and should not eat. In this age, the consumption of tea and condiments has increased greatly. No one can deny the need to be strict regarding their use. One can contend that it should be possible to eat less and be a fruitarian. I believe that this is not possible. Because while food which is considered good is being cooked and its aroma wafts up to you, and others are praising the cooking, doubts arise as to how, as a fruitarian, one could be indifferent to it. It is difficult to ascertain the precise quantity of food that one should eat. I believe that a fruitarian who eats within limits does not ever fall ill. If a fruitarian or someone who abstains from ghee, milk, etc. can show that he has not taken ill in ten years I would accept that everyone should become a fruitarian. Exceptions must not be used to illustrate the success of this diet.

It is often asked, “Where are the restrictive impositions in the Phoenix Institution?” Such a contention is unacceptable to me. Because whatever I did there, and saw others do, I felt that their conduct was enforced by fear. It was as if everything was based on one principle: “Let the groom die, let the bride die, but do as Bapu says.” And it is a fact, Pitaji, that those who believed so became dear to you and those who did not were despised. This was especially true for us; and among us, it was I who was so despised.

If one joined the Phoenix Institution with awareness of this rule he should be willing to give his head when asked. If not his head, he should at least be willing to make sacrifices. The stated norm is that one should not do what appears wrong, that one should fight what is wrong, that one should be fearless. To then call those who are fearless and who oppose the wrong “ignorant” and “stupid”, to withdraw affection from them, to refuse to even look at them, and to taunt them by saying “Ji” in response to their questions was unbearable for me, Pitaji. I have stated that all the members of the Phoenix Institution act out of fear. I felt that under such circumstances I would not become a servant of the country and my soul would not be enlightened. In the institution I saw everyone wanting to establish their own authority by belittling others. Generosity—I found lacking. I witnessed poisonous rivalries. I saw the sense of brotherhood decline. I found everyone lacking in public courage. I found each one covering up their views for the sake of their own interests. I wanted to learn fearlessness, but instead, I saw myself benefitting through hypocrisy.

It is said that moral restrictions - even if they are labeled as fear—are natural. No one experiences fear over moral injunctions. (If one is not immoral.) If a man who drinks alcohol refrains from doing so either out of fear or shame, his behaviour may be regarded as being attentive to a moral restriction. But to experience fear while eating sugar cannot be identified as observance of a moral injunction. This fear becomes coercion. Because, a person who eats sugar would do so in presence of others, but a drunkard would not drink alcohol in the presence of others; if those around him were also drunkards that would be quite another matter.

I am required to perform an unpleasant duty; but I do believe that I can perform this duty to completion.

Pitaji, whenever we told you “We do not benefit from the Phoenix Institution” or “We have not seen others gaining from the Phoenix Institution”, you told us to follow the example of Murabbi Bhai Shri Chhaganlal and Murabbi Bhai Shri Maganlal. You have not said so but have indicated through your actions that we should follow Bhai Jamnadas. We should keep them as our ideals.

I have been bewildered whenever you have said so; because, I have neither been able to bear it nor have been able to express what I have observed. They are my elder brothers and I am ready to serve them and press their feet. Bhai Jamnadas is for me like Bhai Manilal. It is my duty that I should not hide my humble thoughts from you. Such is also your wish. I am performing such a duty by informing you of what I consider necessary.

Their example teaches us to nurture our self-interest. I do not intend to say that they have adopted both right and wrong means to further their selves. I have observed that their foundation is the maxim “Honesty is the best policy.” I believe that for them abstinence from milk for the sake of it is secondary. I fail to see the significant sacrifices that they have made. Bhai Jamnadas who is a part of your organisation could have sacrificed two or three years and refrained from encouraging child marriage. In Rajkot (it is necessary to remember here that you were prepared to break off my engagement) he created an impression that no one comprehends or practises your ideas as much as he does. You would say, “Should he not obey his parents?” If he had remained subservient to the conservative religious ideas of his parents, he could not have transgressed caste and community rules. Moreover, he got married, he enjoyed the life of a householder for three months and then he joined the Phoenix Institution by taking a vow of lifelong celibacy. All this appears to me very perplexing. I fail to understand what lesson I should derive from it. If Bhai Ramdas were to follow his example, he could marry whenever he desires—perhaps immediately. Because after the son attains the age of sixteen you consider him a friend and do not insist that he should act contrary to his own desires. He can not only get married, but after marriage he can directly join your institution.

Moreover, since there is no question of seeking deferment from you, it is asked, “What should we do, if we go there, to earn for ten years?” Based on such considerations, there is the answer “One cannot join your institution.” Since we have touched upon the question of earning I must say that the plan of Murabbi Bhai Shri Chhaganlal, Murabbi Bhai Shri Maganlal and Bhai Jamnadas to earn a living out of you is simple and superb. They have brought with them their characters. They use this character and keep you happy and pleased. They give their character to you and trade in the capital that is your character. In this transaction you have given them everything. But they can take only what their destinies allow them. There is an additional advantage of investing capital in your firm—there is no fear of losing out on the interest; each per cent of the interest is calculated and paid.

But, you have given us no capital. That is my quarrel with you. If you had given us some capital we could have traded with some firm. What are the consequences of this? We trade without capital. In business the norm that one must remember is that accounts must be calculated to the last paisa even with a brother. Therefore, people mock us. “Go away, you free-loaders. You are eating out of your father’s earnings. Why are you putting on airs?” (What airs? That I am a son of M.K. Gandhi.) What do you, with whom we could have traded, say? “Go away, stupid fool. I feed you but you don’t even know how to eat?”

How can we feed off you? How could we possess a trader’s cleverness? From where could we have gained the experience of such transactions that we could have become adept at them? A dog that roams the farms belongs neither to the road nor to the village. Clever—It cannot be. Pitaji, you have kept us in such a condition. What example should we follow?

If Bhai Manilal were to follow the example of Bhai Jamnadas - he would not do so because I think the worm has become a wasp, but still—he could escape from the work that he now does at Shantiniketan—of cleaning the sleeping quarters of Mr. Andrews, making tea for him, etc. You have made all of us do such work. I have seen Bhai Jamnadas escaping from such work as he considers it lowly.

Bhai Manilal addresses me by my name because Bhai Jamnadas does that. Bhai Manilal is elder to Bhai Jamnadas both in age and relationship. But still, Bhai Jamnadas calls him Manilal. Vashisthaji used to address Vishwamitraji as “Rajarshi”. I do not know if such is the case with them. I have no objection to it. But in our family and among us it is considered discourteous and insulting.

People wonder that if not much, something should have happened at the Phoenix Institution, some training in literacy should have been imparted. It is my view that no training in literacy has been imparted whatsoever. You admit that such training has not been imparted, but you also insist that such a sacrifice had to be made. We began making sacrifices around 1907.

But many of us belong to the Phoenix from long before. All of us, and especially we brothers, have expressed our deep desire to acquire education, but you have never paid any heed to us. It is doubtful if Bhai Manilal, Ramdas and Devdas at the age of twenty-three have the knowledge of a fourth grader.

Pitaji, I have not been able to say even one-fourth of what I have to say. The letter has become very long. Printing is expensive. From where will I find the money to pay for it?

Before I conclude, Pitaji, if I have unknowingly expressed rash and immature ideas I seek your forgiveness from the depths of my conscience. At the age of twenty-eight I have been forced to write to you like a young child; this pains me, but I had no other choice. My conscience dictated the letter and I merely wrote it. Whatever I have said about the Phoenix Institution I have said because of my blood relations with it. Therefore, I have pointed out only its shortcomings. The virtues of the Phoenix Institution are known to the world.

My entire letter stresses one point—you have never been generous and patient with our failings. You have never considered our rights and capabilities; you have never seen the person in us. Your life and actions are very harsh. I consider myself unsuitable for a life such as yours. To you a son and others are equal. If there be two accused—one of your sons and someone else—you have considered it unjust to regard the other as guilty. It is justice that a son must suffer, but unfortunately I have not been able to bear such suffering.

Moreover, whether it is right or wrong, I am married. God has granted me four children. I am caught in the web of worldly relations, in its delusions and enchantments; I cannot acquire the detachment of an ascetic and renounce the world like others. Therefore, I had to separate from you with your consent. I feel that I must earn my own livelihood. Even after this I am willing to join the Phoenix Institution at your command. You know that

I have not disobeyed you on purpose. It is possible that my views are wrong. I hope that they prove to be wrong—if I realise that they are wrong I shall not hesitate to reform myself. In the deep recesses of my conscience, my only desire is that I be your son— that is, if I am good enough be your son.

Your obedient son Harilal’s Sashtang Dandvat Chaitra Sud

Purnima

Samvat 1971

31 March 1915 Mumbai

(Letter and Photos excerpted from Gandhi: An Illustrated Biography by Pramod Kapoor with permission from Roli Books)

Tags