Pause And Listen

Artists' Diary: Partners In Art

Into the world of Moonis and Baaraan Ijlal

In the forest, we stopped by three elderly women who sat together on the ground and arranged flowers and tiny portions of food—a small piece of meat with boiled millets of kudu and kutki, velvety tendu fruit, sticky ball of mahua laddoo, all arranged on a plate of leaves. They left it under the tree. We crossed paths, we had nothing to say to them, no greetings, no apologies for stopping. We cut across the forest, like the jaabir, only taking things in—the fragrance, its million undefined hues.

We were there to check if all was well in the state-protected forest. One of us boasted how recently he and the village elders had “amicably” settled a case of rape in the forest. We did not heed the story. We also did not acknowledge the homegrown meal the women had served to the forest. We didn’t acknowledge that the trees were different from one another, that they nourished each other through their tangled roots and branches. We didn’t acknowledge that the fruits on them were different.

Missing The Forest...

The blurb in the science paper said the policy of planting compensatory forests has resulted in monoculture plantations, which are neither forests nor are they able to compensate for the loss of biodiversity when a real forest is cleared. We did not even read the paper because it did not match our dreams: the dreams of the gun-headed jaabir.

Once we spent a night at the fringe of another forest in the north. We woke up to the calls of the deer and fell asleep again. The next day, the buffaloes and goats of the forest-dwellers kept interrupting our “important conversations”: was it because we had overstayed with the family of men, women, buffaloes, goats, horses and their children? One of the women said the buffaloes were telling them that it was time for all of them to move further up the hills. For centuries they had been living between the heights, digging small ponds of water which keep the mountain earth hydrated. But now the forest is officially off limits to them and extreme heat has evaporated the ditches and ponds. That’s why the deer come calling at night, looking for water.

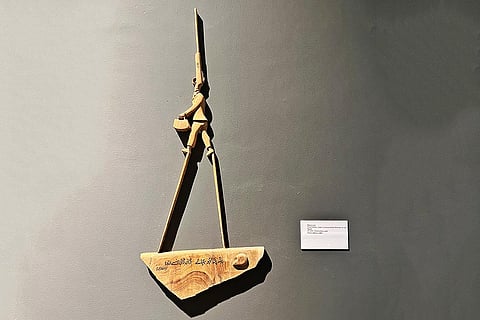

Hostile Witness is a series of paintings by Baaraan and sculptures and structures by Moonis that tell a recurring story of loss and damage through literary symbols of hope and oppression.

The Jaabir

We live with the planet, or like the Jaabir, we live off it. Jaabir: the self-destructive consumer, the coloniser, the gun-headed oppressor who sets the forests on fire and destroys the deep seas. Do we become the oppressor when we witness everything on the planet treated as raw material, silently? We also silently see aging women left homeless in the city. Conceptually, Hostile Witness, the series of paintings, structures and sculptures argue that to fix the climate crisis humans must acknowledge and fix the historical wrongs that have normalised economic and social discrimination. As social scientists put it: the climate crisis is not an engineering challenge, instead it is a social and policy battle. We realised the difference when we partly lost our ancestral home to the malls.

Elephants In The Room

In the Old City in Central India, things one needed were nearby. The children could run out of the courtyards to full-fledged bazaars outside in a game of hide-and-seek. But by the start of the 21st century, commercial real estate drove the children out of the courtyards and bazaars. It made economic sense to lose the enclosed garden, its small fountain with the baby fish, and the guava, fig and pomegranate trees. Ten families lived in the rooms around the courtyard. Most of the homes were like this. The shops faced the streets, the room faced the trees. Malls have erased those names and places. We moved to apartments in the suburbs which were once forests. Now we drive miles in cars to the malls. We do not acknowledge the loss of our homes and bazaars. We have no memory of them.

Speaking of memory, a science paper says human settlements in Madhya Pradesh have suddenly come in the middle of elephant corridors. Since 2010, elephant numbers in the state have increased from one to over a 100. Scientists say the elephants are tracing their genetic memory to their old corridors. When their habitat is threatened, they reclaim their old corridors, that’s why they are travelling over 350 km from Chhattisgarh all the way to Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli where they have been spotted after 300 years.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Artists' Diary")

Moonis Ijlal & Baaraan Ijlal are Delhi-based artists