The eyes itch. The nostrils sting. You start breathing deep, gulping in large amounts of the acrid, smoke-laden air. Your lungs burn. The foul air is so thick you can almost taste the bitterness on your tongue. You look up…and see nothing. Just the hazy blanket of smog. The sun is just a pale disc on the dark, brooding sky. You hear vehicles passing through the near-invisible streets. People walk past, just metres away, and all you can see are silhouettes. It looks like a scene straight out of an apocalyptic movie. But this is very real. This is north India in winters. And this is at the heart of the unfolding story of India in an ever-growing war against air pollution. It’s the story of the evil that put masks on Indian faces long before the world was convulsed by the coronavirus.

Chokehold

Air pollution kills millions every year. This winter, experts warn that a collusion between coronavirus and particulate matter will exacerbate infections and related deaths. What are we doing about this clear and present danger?

Delhi-NCR may get all the media attention for its notorious air pollution, but the grim fact is that close to a quarter of India’s population—around 258 million—living in the Gangetic plains risk losing about nine years of their lives due to high pollution levels, says an Air Quality Life Index 2020 report by the Energy Policy Institute of the University Of Chicago. Only Bangladesh is worse than us on a country-level assessment. Air pollution, the report says, is a bigger killer than the raging COVID-19 pandemic.

ALSO READ: Warrior Moms, Crusader Kids

Around this time every year, north India faces its worst nightmare—thick plumes of smoke from stubble burning in Haryana and Punjab spreading across the region, and Diwali dumping more pollutants from fireworks and crackers. As wind speed falls during the winters, the smog is trapped close to the surface where exhaust fumes from millions of vehicles and hundreds of factories turn the region into what was once memorably described as a “gas chamber”.

Evil Twins

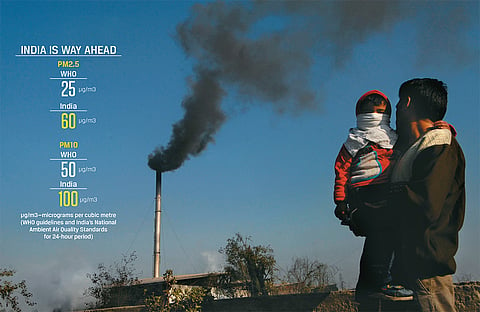

For scientists and the common man alike, the villain—villains, if you please—of the piece is the innocuous-sounding ‘particulate matter’, commonly referred to as PM in living room and academic discussions. Scientists measure particulate matter in micrometre or micron (1 micrometre=.001 millimetre) and group them into broadly two categories—PM10, measuring 10 microns or smaller and PM2.5, which measure 2.5 microns or less.

ALSO READ: Startup Army Is Airborne

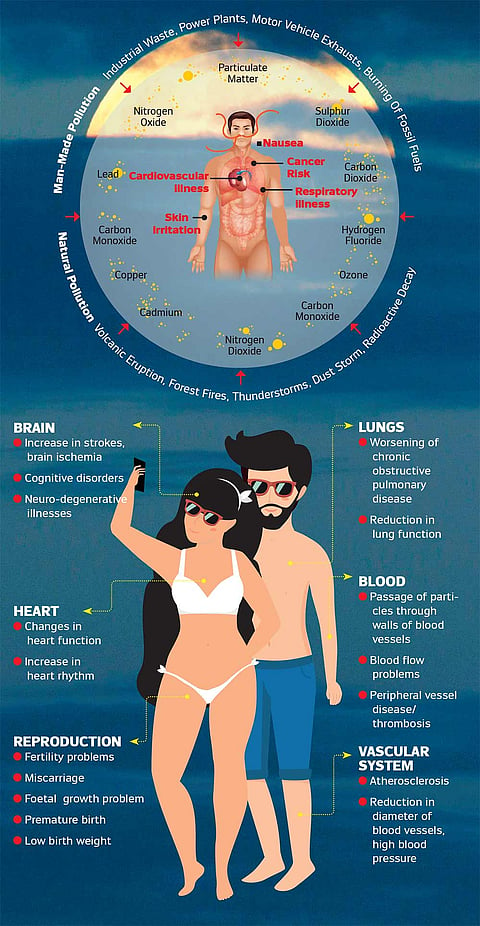

On an average, an individual inhales about 14,000 litres of air every day. Concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 are causing millions of deaths, brain damage and other respiratory problems in India and across the globe annually. The PM2.5—about 1/30th of the size of a human hair—are considered more lethal as they can penetrate deep into the respiratory tract and lungs, bypassing the filtration of nose hair, causing irreparable lung diseases. Over time, they accumulate in the lungs and by diffusion enter the bloodstream, causing cancer, strokes and heart attacks or damaging other parts of the body, including the brain.

“Particulate air pollution is extremely hazardous, even more than smoking cigarettes, and shortens lives globally. There is no greater current risk to human health,” says Michael Greenstone, Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor in Economics, University of Chicago.

The World Health Organization (WHO) says a safe daily level of PM2.5 is 25 µg/m3 (µg/m3—micrograms per cubic metre). But across the urban landscapes of north India, PM2.5 levels have already hit “hazardous” levels. Last year, PM2.5 levels in Delhi touched 999. It could have been even higher, but the sensors on the devices are not calibrated to read beyond that. Just to give you an idea how poisonous is such air, pollution levels between 301 and 500 are classified as “hazardous”, meaning everyone faces a risk of respiratory effects and should stay indoors.

ALSO READ: ‘Our Clean Air Plan Is A Shot In The Dark’

“In spite of all the scientific evidence, there is a lack of knowledge among the masses on particulate matter and air pollution as a public health hazard. The world has to embrace the seriousness of air pollution crisis,” Maria Neira, WHO director on public health, environment and social determinants, said last month while addressing the annual convention of the Clean-Air Collective, a pan-India network of organisations and individuals. The deliberations projected industrial emissions to be the fastest growing source of all critical air pollutants. And it is a significant source of all PM emissions in tier 1 and tier 2 cities in the country, as highlighted by the Centre for Study of Science, Technology and Policy.

Even more scary is the fact that India’s National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) set in 2009 is much lower than the one prescribed by WHO, especially on PM2.5 and PM10. But official data for 2019 show that PM10 levels in 246 cities and PM25 levels in 39 cities exceed even that of NAAQS. On the basis of annual average data, percentage of cities exceeding NAAQS with respect to PM10 is 77 per cent and PM2.5 is 33 per cent.

ALSO READ: 0 Breathability

This year, there is another angle to the concerns over rising air pollution. And the Lung Care Foundation in Delhi and its collective—Doctors For Clean Air—have already raised the alarm. There is significant evidence that the corona pandemic can go from bad to worse if a study from Harvard University holds true—that an increase of 1 µg/m3 in long-term PM2.5 exposure is associated with an 8 per cent increase in COVID-19 mortality rate.

“Evidence available from around the globe has shown that areas with high air pollution levels have experienced not only higher incidence of COVID, but also higher mortality among corona positive people. This becomes particularly relevant for our set-up where the pollution levels are expected to go up significantly high in the next few months because of resumption of activity as well as crop burning…. With proactive and quick measures, we can overcome this problem,” says Dr Arvind Kumar, founder and managing trustee of the Lung Care Foundation and chairman at the Centre for Chest Surgery, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi. There are at least 13 research papers in circulation that indicate that the spread of coronavirus will accelerate with rise in PM2.5 levels in the air.

ALSO READ: Throwing Straws Against The Wind

A road-building spree could also aggravate matters, given the fact that the authorities have never considered the role asphalt plays in air pollution. Peeyush Khare from the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, Yale University, and colleagues, said in a research article that “in hot weather conditions, particulate matter emissions from asphalt in roads can cause a bigger problem than emissions from all petrol and diesel vehicles”.

Lockdown Revelations

Besides the usual suspect, particulate matter, there are two other critical pollutants of concern—nitrogen dioxide and ozone—out of 13 listed for regulation. But often, their presence is masked by the excessively high particulate pollution in urban areas. As a result, the Air Quality Index (AQI)—the daily measure of pollution levels—is dominated by PM10 and PM2.5 contamination.

The coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns threw up interesting data on air pollution. With vehicles off the road and factories shut, there was a drastic collapse of concentration levels of particulate matter and also other pollutants. Instead, ozone started to show up as the lead pollutant in the daily AQI bulletin of the Central Pollution Control Board. This was evident in several cities. During April and May this year, ozone was the lead pollutant in Chennai for 59 days, in Delhi for 48 days and in Calcutta for 57 days, a considerable upswing from 10, 20 and three days respectively recorded in April and May 2019 for the same cities.

Ozone on the ground level is known as a ‘secondary pollutant’ as it is not directly emitted by any source, but is a result of a chain of chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides and various volatile organic compounds arising from emissions by heavy industries, including power plants, and vehicles during the daylight hours. Inhaling ozone is hazardous as it causes lung damage. Even minute amounts of ozone can cause chest pain, cough or worsen bronchitis and asthma. Further, on the ground level it is the chief ingredient of the dirty grey smog that is now a constant feature of our winter months.

ALSO READ: How To Not Waste A Crisis

“Urban air pollution is not a new problem or an easy one to explain,” says Sarath Guttikunda, director of Urban Emissions (India), an independent research group on air pollution that disseminates air quality forecasts for over 640 districts in India. “Each pollutant is associated with a range of health impacts, partly linked to the source of the pollutant. For example, PM leads to respiratory illnesses, ozone pollution leads to eye and lung irritations, SO2 (with precipitation) leads to irritation along the respiratory track and bronchitis, NOx enhancing the symptoms for chronic bronchitis, and CO reducing the oxygen supply to the brain (and in some cases fatal).”

There are even more stark data. A collaborative study by IIT Bombay, the Health Effects Institute and the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation found that residential biomass fuel burning contributed to the death of nearly 2.68 lakh people in 2015. Coal combustion in thermal power plants and industries contributed to 1.69 lakh deaths; anthropogenic dust contributed to one lakh deaths; agricultural burning contributed to 66,000 deaths; and transport, diesel and kilns contributed to over 65,000 deaths in India.

Clean Air Plan

During his Independence Day speech this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi raised the topic of air pollution and said his government is “in a mission mode” to reduce pollution in 100 select cities across the country. Earlier in January 2019, the Centre had introduced the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) as a national-level strategy to reduce air pollution. It has set a national level target of 20-30 per cent reduction of PM2.5 and PM10 concentration by 2024 (2017 is taken as the baseline year for data). One of the key highlights of the 106-page report is the proposed implementation of city-specific air quality management plans for 102 cities, which did not meet the NAAQS. The National Green Tribunal later added 20 more cities to the list.

ALSO READ: The Trash We Inhale

However, an assessment report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) and Urban Emissions points to “significant shortcomings that could potentially derail the implementation process”. The authors say “there is no legal mandate for reviewing and updating plans and actions in the plan cannot be prioritised without information on the contributions of different sources”. They found only 25 of 102 city action plans contained data on emissions from different sources. Further, there is no single agency that could be held responsible for the implementation of each city’s clean air plan. A chunk of the activities is to be shared among multiple agencies, like the State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB), urban local bodies or transport departments.

“There is a lack of technical knowledge among officials in SPCB. Also, there is no robust system to track real-time data from various sources, collate and process them. The majority of the air pollution units is still manually operated,” says Tanushree Ganguly, programme associate at CEEW and lead author of the report. CEEW’s review finds all the city-level clean air plans as a collection of measures without specified goals and priorities. In fact, about 90 per cent of the 102 approved city-specific clean air plans do not have budgetary provisions. And surprisingly, the mitigation plans are identical whereas each city has its own individual source problem; 14 of Uttar Pradesh’s 15 cities have identical plans. The case is similar for multiple cities in Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and J&K.

“NCAP needs to go beyond the city limits and look at regional levels with a multi-jurisdiction framework, identify local hotspots and put mitigation measures in place to reduce exposure. Around 60 per cent PM emissions are related to industrial plants, including power, and we are not meeting any standards,” says Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director at the Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

At least, 70 per cent of the actions mentioned in NCAP involve overseeing, planning, proposing, preparing, investigating, identifying, ensuring, strengthening, training, studying and engaging. Which means there is negligible amount of actual pollution control measures.

Emissions from industry and burning of biomass far exceed vehicular emissions, the most talked-about sector. “If we only consider the amount of materials we burn, then at an all-India level, 85 per cent of air pollution comes from the burning of coal and biomass; oil and gas contribute less than 15 per cent,” says Chandra Bhushan, president and CEO of the International Forum for Environment, Sustainability and Technology (iFOREST) and an expert on environment and climate change. (See ‘Our clean air plan is a shot in the dark’)

In the midst of the lockdown, Prime Minister Modi announced the auctioning of 41 coal blocks for commercial mining under the Aatma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan. “We are not just launching an auction for coal mining, we are taking the coal sector out of decades of lockdown,” Modi said, but made no mention of environmental concerns raised over the government decision.

Stubble or crop residue burning has dominated news headlines as a significant source of air pollution in recent years. India burns 1800-1900 million tonnes of fossil fuels, biomass and waste every year. Of these, 1500-1550 million tonnes or 85 per cent are just coal, lignite and biomass. They also happen to be the most polluting fuels.

Experts agree that cutting emissions from coal and biomass burning must be given topmost priority as this has the added benefit of reducing indoor air pollution and hence saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of womenfolk (as they are the ones who mostly cook and work in the kitchen). It is not only the ambient air quality in cities, but also indoor air quality in rural and urban areas that are causing concern. It’s estimated that we spend around 90 per cent of our time indoors every day.

Curbing emissions from thermal power plants and industries has to be the next priority. This is a difficult one—our pollution monitoring and enforcement systems are extremely weak, and we will need massive innovation and cutting-edge technology in pollution control, especially for small-scale industries, to accomplish this. “We have seen how the lockdown had flattened the pollution curve and then we noticed a surge when the economy started to reopen…. A reduction in cities is only possible if the entire region cleans up together. The change has to happen at scale and speed across all critical sectors including vehicles, industry, power plants, waste, construction, use of solid fuels for cooking and episodic burning. We also need good science to assess air quality based on the ever-expanding monitoring grid for a better understanding of the changing trends in different pollutants,” says Roychowdhury. “Building public and political support for harder decisions is critical now. We need scale, effectiveness and accountability.”

How did China cleaned up its act after the 2008 Beijing Olympics tarnished its image? As part of its clean air action plans, the Chinese government prohibited new coal-fired power plants and shut down many old units as well as coal mines. It restricted private vehicles on city roads and introduced fleets of electric public transport. Between 2013 and 2017, Beijing reported a drop of 33 per cent in PM2.5, although current levels are higher than WHO guidelines.

For a country trying to match the Communist neighbour on all fronts, these are lofty targets. But not unattainable. Sarath Guttikunda emphasises that only a sense of the magnitude of the problem will allow policies and action. The magnitude of the problem was brought to sharp focus in a new global study that said more than 116,000 infants died from air pollution in India last year.

The State of Global Air 2020, produced by the United States-based Health Effects Institute (HEI) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Global Burden of Disease project, also noted that following the pandemic “many countries around the world have experienced blue skies and starry nights, often for the first time in many years”, though short-lived. “Nonetheless, the blue skies have offered a reminder of what pollution takes away.”