Rhea Chakraborty, 28, is not an A-list star with a string of box-office hits to her credit. Far from it. After years of trying, she remains a struggling actress trying to get a toehold in Bollywood. Yet, she presently finds the spotlight shining on her—glaringly and unremittingly—making her the most-talked-about woman in a way she could not have imagined in her worst nightmares. All thanks to a non-stop media trial—going on across several news channels. They are not merely depicting a legal thriller—that newly favourite genre; rather, they have themselves morphed into kangaroo courtrooms that have had no qualms in pronouncing her “guilty” in the Sushant Singh Rajput death case. All this without the CBI even having filed a chargesheet against her as yet.

Daily Noose

The coverage of Sushant Singh Rajput’s death has turned into a ghastly media trial of Rhea Chakraborty. As the hawks swoop in, ethics, propriety and due legal process have gone for a toss.

Ever since the 34-year-old movie star was found dead under mysterious circumstances at his Mumbai house on June 14, there has been a wave of curiosity, mostly sympathetic, and an overwhelming desire to see justice done. Too many people suspect foul play in his untimely death, which was initially passed off by Mumbai police as an open-and-shut case of suicide. Those trails are opening up, but the media appears to be in a tearing hurry to take the case to its own conclusion, logical or not, without bothering to wait for the findings of law enforcement agencies or, for that matter, for the judicial process. Today, the average TV journalist subsumes all those roles in an all-in-one justice system: the media is by itself investigator, prosecutor, jury, judge…and executioner.

ALSO READ: Judge And Hangman

The CBI is now interrogating people close to Sushant, including his erstwhile live-in partner Rhea. Why then is a parallel trial being run by TV media? Simple. Media trials sell more than sex and Shahrukh on prime time! Patience and respect for journalistic norms are always difficult virtues to hold on to in the cutthroat world of visual news media, but a case such as Sushant’s death unleashes an outright feeding frenzy, a mad race for TRPs. Thus, glitzy TV studios have upgraded themselves into courts of law and news anchors have morphed into the new milords, self-appointed arbiters of justice. This self-aggrandisement relates directly to their bottomline: they literally profit from it. ‘Revelations’—true or not—bring revenues.

A New Delhi-based model Jessica Lal, who was a celebrity barmaid at a party, was shot dead in April 1999. Manu Sharma, the son of a politician, was arrested and convicted in the case after a gruelling legal battle. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in December 2006 and released from jail in June this year on grounds of “good behaviour”.

No wonder the TV news industry has lapped up the Sushant case: its immense potential to boost TRPs is not just theory. It’s borne out by figures. The early birds appear to have been the immediate beneficiaries. Republic channel, which launched the #JusticeForSushant campaign, ended up getting more eyeballs than all other English news channels put together in recent weeks. Its Hindi counterpart, Republic Bharat, reportedly also raced ahead of Aajtak, the Hindi channel leader for years, primarily because of its over-the-top coverage in the case. In the weekly data released by the Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC) for the week between August 8 and August 14, Republic TV had a market share of 52.65 per cent, more than that of all its rivals put together. “Republic Media Network shatters all records. Republic TV channel soars to 52% and Republic Bharat now the Number 1 Hindi news channel across India. Thank you, viewers, for making Republic Media Network the number 1 news network in India,” the Arnab Goswami-led channel tweeted. It’s a dead giveaway of audience preferences too: forget all the ballyhoo over violation of journalist ethics, viewers evidently love to consume a good media lynching along with their organic breakfast, lunch and dinner.

ALSO READ: Swimming With Tuna

According to another report by BARC and market research firm Nielsen, the Sushant case had the maximum coverage on news channels between July 25 and August 21. Except in the first week of August, when the Ram temple Bhoomi Poojan grabbed the top slot, the Sushant case dominated the news channels for the past two and a half months. Are channels catering to public demand, or are they creating the demand in the first place? Either way, rival channels were to be seen trying to outdo each other in ‘unravelling the Sushant case’ in their own way. All manner of ‘independent investigations’ are being carried out across channels, including reconstruction of crime scene, autopsy, forensic and polygraph tests—not to speak of séance sessions with the spirit of Sushant!—all to keep the viewers on the edge of their seats. Media trials are not exactly a new phenomenon in India: remember the prosecutorial arrogance in the Aarushi Talwar case? But with each new edition of the phenomenon, the low blows, the luridity and the size of the lynchmob have increased. In this case, libellous slander has officially become an industry in itself.

ALSO READ: The SSR Mega Serial

These are not the best days for upholding somebody’s privacy as a mark of cultural maturity or a liberal virtue. The ambient voyeurism is nearly pornographic. The Bihar-born actor, known for Bollywood hits like M.S.Dhoni: The Untold Story (2016) and Chhichhore (2019), is being posthumously accused of being a drug addict, bipolar and a womaniser on live TV debates. Even medical prescriptions from psychiatrists for ‘treatment of depression’ during Sushant’s last few months are being flashed on screen. Alongside, Rhea is also being vilified as someone who “conspired with the Bollywood mafia and drug cartel to get Sushant killed”. That this precedes actual investigation, and that there’s still no incontrovertible proof in the public domain, is a minor ethical quibble for which there’s no screen space.

Sunanda Pushkar, wife of former Union minister Shashi Thaooor, was found dead in a hotel room in Delhi in 2014. A controversy followed over the cause of her death, leading to a sustained media trial soon thereafter, where it was discussed whether she died by suicide or was killed. Tharoor was later charged with abetment to suicide in May 2018. The matter is sub judice now.

Media observers believe some channels have crossed all limits with their misogynistic coverage on Rhea simply because her image of a glamorous ‘starlet’ who had entered into a live-in relationship with her boyfriend did not conform to orthodox middle-class norms. Since she was not a successful actress, they argue, she was branded as a gold-digger who lived off the fortunes of her rich boyfriend. The channels, of course, chose to dig for gold outside her house on Juhu Tara Road, Mumbai, where a pizza delivery boy exhibited way more decency and fortitude than the combined carnivorous media posse that pounced on him, among other people.

Have we seen this before? Yes, indeed. The Aarushi case, where we saw everything from incest upward peddled. The Sheena Bora case, whose tangles defy description. And yes, the Sunanda Pushkar case, where Arnab Goswami declared triumphantly to Shashi Tharoor on TV—in the mode of Alexander during the Siege of Tyre—that “my reporters have surrounded your house”. Tharoor filed a civil defamation suit in 2017 against Arnab in the Delhi High Court, claiming compensation of Rs 2 crore for “defamatory remarks”. In 2019, a Delhi court also ordered registration of an FIR against Republic TV and Goswami, on a complaint by Tharoor, alleging theft of confidential documents pertaining to the probe.

Very few have fought back against a media organisation after being targeted unfairly in a media trial. Poet and scientist Gauhar Raza, for one, had first-hand experience of what wrong reporting can do, but he decided to take on a news channel. Recalling his case with a shudder, the former CSRI head says he was described as a member of the Afzal Guru gang on TV channels. “The atmosphere was such that anyone could have attacked me had I been spotted alone outside my house,” Raza reminisces. “I used to be scared all the time. But I fought back. Zee Network had to apologise for it later.” In a “media trial against an innocent on the basis of an utter lie, the victim becomes completely helpless,” he says. Other innocents too have borne the brunt of unfair media trials. ISRO scientist Nambi Narayanan, for one, had to endure a prolonged bout of it after being branded a spy in the 1990s.

ALSO READ: Naked Among Wolves

Salacious gossip is often deployed as a clincher in such cases—even if they be proved wrong later. With celebrity cases, this acquires an extra buzz. Popular tropes about high living permeate these depictions: drugs (pharmaceutical or psychotropic), spouse-swapping, promiscuity, illicit relationships. The public’s capacity for prurience and schadenfreude are what they tap into: Sridevi’s death saw one reporter doing her piece-to-camera from next to a bathtub, another lowered himself entirely into pink porcelain! This time too, all the ingredients for an OTT potboiler are present, or can be added if missing, so why let Netflix have all the fun? Prime-time news can itself turn into a Netflix blockbuster that you binge-watch. ‘Bollywood-politics-drug mafia nexus in actor’s murder’…who cares if any of it is true? All are on board the gravy train.

The high-voltage coverage has naturally not passed the test of the Press Council of India, India’s primary media monitoring body, a largely toothless one whose advisories sound more like innocuous lamentations. On August 28, it “noted with distress” that media coverage of the Sushant case was largely “in violation of the norms of journalistic conduct”. It “advise(d)” the media to adhere to norms framed by the Press Council: specifically, that no one should “narrate the story in a manner so as to induce the general public to believe in the complicity of the person indicted”. Further, no gossip or speculation about the official line of investigation. “It is not advisable to vigorously report crime-related issues on a day-to-day basis and comment on the evidence without ascertaining the factual matrix. Such reporting brings undue pressure in the course of fair investigation and trial,” it points out. And victim, witness, suspect, accused—all have their rights, including the right to privacy. “Identification of witnesses…needs to be avoided as it endangers them,” it said. Pressure can come on them from the accused, his/her associates, even investigating agencies, it pointed out. Therefore, its conclusion: “The media is advised not to conduct its own parallel trial or foretell” the judicial decision.

ALSO READ: Fright Nights

Alas, for all the fine sentiments there, the operative word is “advised”. No wonder, therefore, that all channels are observing its tenets in the breach—in both letter and spirit. To begin with, the PCI, constituted in 1966 as an autonomous, statutory, quasi-judicial body, is a watchdog for newspapers and news agencies, but does not have any jurisdiction over TV news channels as such. And anyway, not being vested with any power to mete out punishment to erring media houses, its censure hardly deters anyone in the dog-eat-dog world of media today.

So who’s responsible for TV channels? Is there at all a regulatory mechanism, an ombudsman? Here, things get really interesting. ‘Self-regulation’ is the name of the game. We have the News Broadcasting Standards Authority (NBSA), an independent body set up by the News Broadcasters Association (NBA) to consider and adjudicate upon complaints. And it’s headed by Rajat Sharma of India TV. That’s not all. In 2019, another body called the News Broadcasters Federation (NBF) came into being, contending that some Delhi-based channels had falsely claimed to represent Indian broadcasting industry. That one is headed by none other than Arnab Goswami.

A 13-year-old schoolgirl Aarushi Talwar and her 45-year-old domestic help Hemraj Banjade were found murdered at her Noida home. In the frenzied media trial that followed, her doctor parents, Rajesh and Nupur Talwar, were considered prime suspects. In 2017, Allahabad High Court acquitted them, but the apex court admitted an appeal against the judgment in 2018.

Sharma defends self-regulation, saying it has proved very effective. “Seventy-one channels that follow NBA guidelines hardly get any complaints from viewers,” he says (see interview). “All these channels, watched by 80 per cent viewers, follow NBSA guidelines that are very strict, and do not cross limits. But news channels that are not members of NBA and are watched by 20 per cent viewers have no such guidelines to follow.” He says the news broadcast industry’s reputation suffers because of these few channels. “We want the NBSA guidelines to be mandatory for all news channels,” he adds.

“Some media institutions have crossed all limits,” says N.K. Singh, former CBI joint director, who admits to having never seen the likes of this in his 34-year career. “They are debating the investigation by calling people who do not even know the ABC of the investigation. The verdict is being pronounced without any evidence. They are mocking the death of a rising film artiste from Bihar. It is quite unfortunate,” he says. The CBI and other agencies are working on the case as per their “standard procedure”, he says. “The media’s job is to raise questions, not to convict anyone. It can destroy somebody’s life.”

Big names from TV, many of whom have competed with each other to jointly create this idiom of sensationalism, tread a carefully defensive line that blends words of virtue and journalistic exigency, even duty. Deepak Chaurasia, consulting editor with News Nation Network Limited, believes the media cannot remain neutral about news—an argument that could be persuasive in a general sense. All major cases are covered exactly the same way, he says. “It is not as if the media is doing it only in the Sushant case. Even in the Aarushi and Nithari cases, the media had probed all angles in a similar manner. Now that a big film star like Sushant has died under unfortunate circumstances, every journalist wants to get to the bottom of the facts,” he says. That the uniformity of approach may not automatically count as a virtue is one thing. But it does point to a consistently applied pragmatic rationale: “Oh, but we HAVE to do it.” Is that the case, though?

Chaurasia also grants that the media must understand it’s the courts that finally decide guilt. Press Association president Jaishankar Gupta takes a dim view of such espousals. “What happened in the Aarushi-Hemraj murder case in 2008?” he asks. “From print to electronic media, headlines like ‘Beti ka hatyara baap’ (daughter’s killer father) were carried everywhere. It created an impression that Aarushi had been murdered by her father. But the high court acquitted him. Did any media institution bother to apologise to Aarushi’s father? Nobody did it, despite having resorted to character assassination. The same is happening now in the Sushant case…the media already done its own trial.”

Indian media’s downfall has been quite perceptible, especially in the cases of actress Sridevi’s death, Baba Ram Rahim’s arrest and now Sushant Singh Rajput’s death. There seems to be a race to show cheap content. Ironically, the cheaper the content, the higher the ratings! Television channels try to cover it up by asserting that this is what the public wants to see…. More often than not, it is argued that a 24-hour news channel has to resort to such programmes. I do not accept such a theory as there is no shortage of good content. I believe the viewers alone can help bring about the change. Such shows will continue to be shown until they reject them.

Sudhir Chaudhary, editor-in-chief of Zee network, when asked, chose to be critical of the argument media barons make: that the onus is on the viewers. “In three cases, Sridevi’s death, Baba Ram Rahim’s arrest and now Sushant Singh Rajput’s death, the media has shown a downfall,” he says. “There seems to be a race to show cheap content. The channels try to cover it up saying this is what the public wants to see, but when you meet in the outside world, they say they do not want to see abusive, noisy arguments on television.” Chaudhary’s own channel has not been exactly free of criticism on the question of media trials or other issues of ethics, but he too cites pragmatism. “Unfortunately, the news medium is linked to a business model where content is no longer a priority,” he says, adding the trend will continue until the public rejects it completely.

Chaudhary, however, admits the Sushant case has seen a historical low. “Maybe some channel will put out a prize scheme tomorrow, where the viewers will be able to ask questions to Rhea Chakraborty,” he says. “It’s a worrying trend.” Claiming that Zee had refused to do an interview of Rhea recently, he says she gave an interview to a channel to garner sympathy barely 24 hours before she was supposed to face the CBI. “Her public relations team was contacting all channels, but we categorically refused the interview offer,” he says.

In that interview, Rhea lamented that she had been implicated in the conspiracy to murder Sushant without any evidence. “I have been charged with having connections with a politician, drug mafia and also the underworld,” she says. “It is all very disturbing. Many times I even thought of committing suicide.” Incidentally, Rhea had earlier moved the Supreme Court, pleading violation of privacy and unfair court-like pronouncements of guilt. Alleging that she has been getting threats of murder, kidnapping and rape on social media, she claimed she had been made a convenient scapegoat in the case for a “political agenda”.

Politics soon entered the frame more visibly. The Sushant case took a curious turn after the Shiv Sena-led government in Maharashtra, which was opposed to handing over the case from Mumbai police to the CBI, alleged everything was being done to help the ruling JD(U)-BJP government in poll-bound Bihar, Sushant’s home state. It was an FIR lodged by Sushant’s father K.K. Singh that paved the way for the CBI takeover of the case. Though both Rhea and the Maharashtra government challenged it on the question of jurisdiction, the Supreme Court gave its nod to the CBI probe. Sena leaders still insist political parties in Bihar are raising the emotive issue for electoral gains. They also allege the BJP is trying to destabilise the Uddhav Thackeray-led coalition government to get even with its erstwhile ally—the Sena had broken ranks with the BJP after the assembly elections last October to form the Mahavikas Aghadi government with Congress and NCP support. That’s why, they allege, the name of Aaditya Thackeray was unnecessarily dragged into the case.

Sheena Bora, a Mumbai-based executive working for Mumbai Metro, went missing in April 2012. Three years later, amid an intense media trial, her mother Indrani Mukherjea and others were arrested on the charge of abducting and killing her. Her stepfather, media personality Peter Mukherjea, was also taken into custody. A 2016 Bollywood movie, Dark Chocolate, was inspired by the case.

Indeed, one of the inflection points en route to the case snowballing into a major controversy was Nilesh Rane, son of BJP leader Narayan Rane, alleging that Aaditya was involved in the case, a charge rubbished by Sena leaders. Similarly, in Bihar, JD(U) leader Sanjay Singh demanded Rhea’s arrest, advising the CBI to use the third degree to make her reveal everything. It is unclear if politics played any part in the events leading up to the death, but the post-death phase has certainly turned bristlingly political in both Maharashtra and Bihar. It’s morphed into “an NDA-versus-UPA battle”, as senior TV journalist Priyadarshan says, while it started out as merely a case with “sensational” elements—a “fertile issue” for media.

But the problem with media trials is that they create such a fog of prejudicial air that it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. After Rhea’s grilling by the ED and the CBI for several days recently, there was media speculation over her “imminent custodial interrogation”. Supreme Court lawyer D.K. Garg questions this kind of pressure being applied. “If the investigating agency gets affected by the media trial, it will not remain an investigation agency,” he says. “It will work in its own way. When it feels a suspect has to be arrested, it will do so. If it feels the suspects are cooperating in the investigation and there is no concrete reason for their arrest, why would it arrest them?”

But some TV experts actually see this as a positive contribution. Rana Yashwant, MD, India News Network Limited, is one of those who believe it’s constructive: minus all the media noise, the case would never have gone to the CBI, he says. “From Rhea’s alleged chat for drugs to her bank transactions, everything has been questioned. The media is entitled to raise legitimate questions in any case, so it is doing it now,” he says. Yashwant wonders why Sushant’s post-mortem report did not mention the time of death. “We have to understand the Sushant case is giving the channels TRPs because new revelations are coming up almost every day.”

Priyadarshan agrees partly: if the public at large assumes the truth is being suppressed in any case, the media’s role becomes important, he says. “If investigative journalism was not there, there would not have been justice in the BMW hit-and-run or the Jessica Lal cases,” he adds. “However, what’s happening in the name of investigative journalism now is that most of the news broken by channels is fed by the agencies. The job of the journalist is to investigate the information on their own, which is not happening now.”

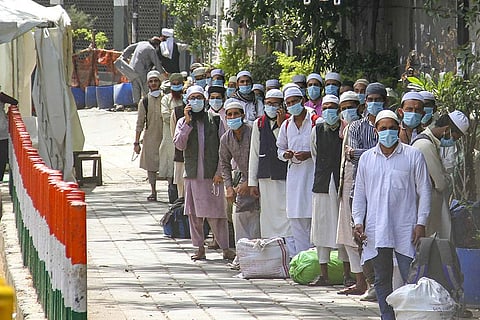

A congregation held at Delhi’s Nizamuddin Markaz by an Islamic sect, the Tablighi Jamaat, was called a “coronavirus super-spreader” on TV after many attendees were found to be Covid-positive in March. Criminal cases against them were filed across India, but the Bombay High Court, in a recent verdict, said a “political government” had tried to find a scapegoat during the pandemic.

Yashwant cites business exigencies squarely, pretty much outsourcing the blame on to the public, saying it’s the TRPs that ultimately matter. “It shows whether people are watching your programmes,” he says. “Today, Sushant is discussed in every household. You can say there are so many issues in the country, and yet the channels are talking about him all the time. It’s happening primarily because the public at large is now in the role of the editor and it wants to know the truth behind Sushant’s death as soon as possible.”

When constitutional institutions bow their heads (to those in power), media forgets the rule of law. Murder in the mobocracy has been seen through political glasses. The death of people standing in queues after demonetisation was considered to be the impact of a patriotic campaign against black money. Media considered it difficult to look at the difficult situation of migrant labourers during the lockdown…. Ignorance with noise and uproar dominates the screens of news channels in such a way that a Congress spokesperson died of a heart attack soon after a live debate. Media did not change even after watching a living person on the screen being carried to the crematorium.

There are some TV names who see a larger malaise. “When constitutional institutions bow their heads (to those in power), the media forgets the rule of law,” says noted anchor Punya Prasun Bajpai. “The deaths in the post-DeMo queues were painted as acceptable collateral damage in a patriotic campaign against black money. The historic protests by Surat’s cloth merchants against GST were looked at askance. These channels didn’t even look at the distress of migrant labourers during the lockdown. Ignorance, noise and uproar dominates the screens.” While some of that may be deliberately diversionary, it has its own victims. “A Congress spokesperson dies of a heart attack soon after a live debate. The media does not change even after watching a living person on the screen being carried to the crematorium,” says Bajpai, caustic about the argument “that they show what the audience wants to see”.

But what could be the way out of this spiralling tunnel of darkness? Self-regulation is a joke. The watchdogs are toothless. Libel and defamation laws are so cumbersome, time-consuming and expensive that victims, already morally and spiritually exhausted, typically shy away from jumping from one kind of court to another. That’s why Manish Tewari, lawyer, MP and former minister for information and broadcasting, stresses the need for an omnibus media regulatory authority of India through a parliamentary enactment, “with adequate powers in place to regulate and monitor both the business and editorial verticals of journalism” (see column). A case could be made out for external regulation turning into an even bigger danger for free expression, but recent debates have zeroed in on a crucial piece of nuance that all may ponder over: freedom of expression is not exactly the freedom to abuse. That is, abuse either a potentially innocent person or freedom itself.