From the quiet, tree-lined three-acre compound of the madrasa, it is hard to imagine there are hundreds of students studying here. There is a majestic mosque to its right, with a squeaky clean marble floor.

Reform Within: How A Madrasa In Madhubani Is Blending Change With Tradition

The Jamia-Tul-Qasim Dar-ul Uloom-Il-Islamia madrasa in Bihar is breaking stereotypes by teaches three languages—Urdu, English and Hindi—along with computers, history, math, geography and science.

The Jamia-Tul-Qasim Dar-ul Uloom-Il-Islamia madrasa in Madhubani village, about 300 km from Patna, breaks the stereotype of a madrasa in many ways. It teaches three languages—Urdu, English and Hindi—along with computers, history, mathematics, geography and science.

(The Jamia-Tul-Qasim Dar-ul Uloom-Il-Islamia madrasa in Madhubani village, Bihar)

Md. Shahjahan Shad, general secretary, Seemanchal Development Board, who is associated with the madrasa, says, “Our aim is to provide the children with both deeni (religious) and dunavi (worldly) education. So madrasa children do not feel alienated when they enter the mainstream.”

The founder, Mufti Mahfoozur Rahman Usmani, popularly known as Mufti Sahab, passed away recently from a heart attack. He started the madrasa in a makeshift hut with only three teachers and 13 children. Slowly, it started gaining popularity among locals. “Usmani Sahab had studied abroad. When he returned to the village, his father said he should do something about it. So, he opened the madrassa in this economically and educationally backward area, which would function like mainstream schools,” Shad tells Outlook.

(Students receiving classes at the madrasa in Madhubani)

It enrols 1,000 children every year. There is also a hostel accommodating 600 students from surrounding areas. Since last year, Covid-19 restrictions have curbed activities. “But now, schools are opening, and we’ve started classes with social distancing,” says Mufti Mohammad Ansar Ahmed Qasmi, principal of the madrasa. He adds, “At present, we’re teaching about 250 children, with around 200 boarders.” The madrasa has a staff of 70 who teach the syllabi of both the madrasa and Bihar boards and admits kids till Class VII.

What makes this madrasa stand out is that it has made sports compulsory. There is a fixed time in the evening when children have to participate in sports. They play cricket, football, volleyball and kabaddi. Qasmi says, “Locals who are good at these sports sometimes come over to teach our students. Also, before the start of morning classes, we make all students run around the campus.”

(Sport is an important part of life at the madrasa)

Class routines vary according to the season. At present, classes are divided into two periods. The first starts at 6.30 am and conclude at 11 am. Thereafter, the children have lunch and take some rest. The second round starts at 2.30 pm, and lasts till 5 pm, after which, they get an hour and a half to play.

When we visited the madrasa, it was already afternoon. The children were trooping out of the hostel rooms towards the kitchen, for lunch. At different locations—some in classrooms, others in the masjid portico—classes had begun with smalls batches of students.

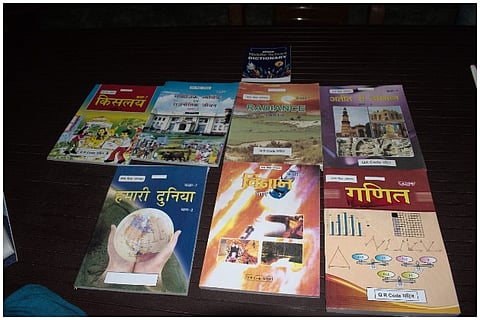

(Textbooks taught at the Jamia-Tul-Qasim Dar-ul Uloom-Il-Islamia madrasa)

“We want to open a medical college in this campus for the betterment of locals. Land for this has been acquired, but due to the lockdown, work is stalled. We’re also planning to build a girl’s hostel, after which we can start offering classes to girls as well. Some Hindu children also attend classes here, often to study Urdu,” says Qasmi.

(Students getting computer classes inside the modern Madrasa)

The madrasa is completely run on donations. The admission fee is Rs 400-500, but economically weaker children are taught free of cost. Admission is easy—all parents need to do is produce identity cards of their wards. The parents also need to sit for a simple test. The quality of education, ambience and focus on sports are all big draws among children who enrol here. Kahaf Zaheer (14), who comes from a well-to-do family and voluntarily pays monthly fees, says, “I was earlier staying at a hostel in Patna, but the quality of instruction was poor there. Hygiene on campus was terrible. So I left and got admitted here two years ago.”