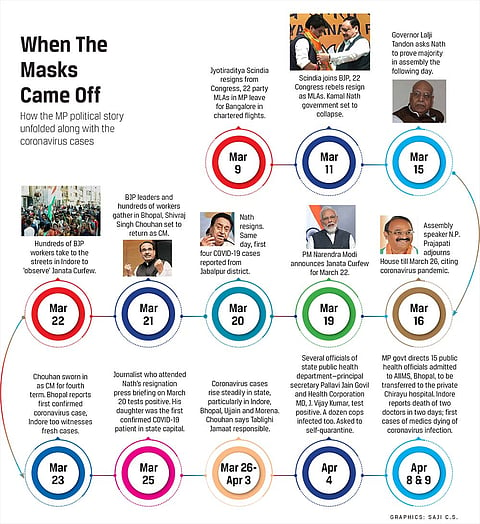

India may still not have a clear answer on the best model for combating the coronavirus pandemic but Madhya Pradesh has offered some critical tips on practices governments must avoid. On March 23, when the BJP returned to power in the state by orchestrating the fall of the Congress-led Kamal Nath government, MP had already registered its first few COVID-19 cases. The political drama that unfolded in the state in the preceding days doesn’t need to be recounted in detail. However, decisions taken by Shivraj Singh Chouhan after he returned as the state’s chief minister for a record fourth term, need to be analysed.

Testing Times: Lessons From Madhya Pradesh That States Must Avoid In Battle Against COVID-19

Holes in MP’s hazmat suit are showing—a CM without a health minister fights a pandemic; private hospitals are getting to treat more coronavirus patients than AIIMS, Bhopal

Chouhan returned to power after a long-drawn political circus in the state that saw Jyotiraditya Scindia and his 22 loyalist legislators ditch the Congress and Nath to switch to the BJP. Perhaps as a natural consequence of the circumstances that pitchforked him to the CM’s chair after a 15-month hiatus, Chouhan wasn’t sworn-in along with his council of ministers. The cabinet, it was indicated by BJP leaders then, would be formed after a compromise was reached between old BJP warhorses and Scindia’s brigade of party-hoppers over ministerial berths. Chouhan could not even choose a limited cabinet with ministers for portfolios like home, finance, health and public distribution. Since the Nath government was toppled before it could present the state budget, there is currently no specific allocation of financial resources across departments while the absence of ministers for the other three portfolios—all critical to proper management of the COVID-19 crisis—cannot be overemphasised.

Chouhan’s administration now appears like a do-it-yourself (DIY) hack where the chief minister must oversee every aspect of the state’s preparedness against the pandemic himself and with bureaucratic chieftains left to do the firefighting. In the midst of this acutely centralised governance model has come, arguably, the most fatal blow to the state’s efforts in battling the health crisis. Practically the entire public health department, responsible for overseeing measures for controlling the pandemic, is now either in isolation wards at hospitals or under self-quarantine.

From Health Corporation chief J. Vijay Kumar, principal secretary Pallavi Jain Govil and several more senior officials of the National Health Mission to low-ranking staff, over 50 members of the public health department have, so far, tested positive for the virus. Before the virus indisposed these officials, Chouhan inexplicably decided to shunt-out health commissioner Prateek Hajela—the 1995-batch IAS officer who oversaw the NRC exercise in Assam—and appointed Faiz Ahmed Kidwai to the post on April 1.

A day before being dismissed, Hajela issued a medical bulletin detailing the state’s preparedness to deal with the pandemic. According to the statement, six government medical colleges in Bhopal, Indore, Jabalpur, Gwalior, Rewa and Sagar with a combined ICU capacity of 394 beds and 319 ventilators and eight private medical colleges with a combined capacity of 418 ICU beds and 132 ventilators had been identified for treating coronavirus patients. The number of COVID-19 cases across MP when Hajela released this bulletin, on March 31, was 66. Evidently, the government-run medical facilities were well-equipped to not just accommodate the existing COVID-19 patients in the state at the time but also had sufficient capacity for treating new cases.

For reasons best known to Chouhan, his government decided to not just draft in select private hospitals in Indore and Bhopal to treat COVID-19 patients but also ordered that all infected public health officials who were admitted to AIIMS, Bhopal, be transferred to Chirayu Hospital, a private facility founded by Vyapam scam accused Dr Ajay Goenka. Similarly, in Indore, Sri Aurobindo Hospital—founded by another Vyapam scam accused, Dr Vinod Bhandari, was identified as a COVID-19 treatment centre.

Health workers in Jabalpur on a drive to screen people for infection, with just masks and gloves for protection.

Doctors in government-run hospitals in Bhopal and Indore are taken aback by “the preferential treatment being given to select private hospitals”. A doctor at AIIMS, Bhopal, says: “We have no problem with the government deciding to shift our patients to Chirayu but what is the point of getting three government hospitals (AIIMS, Hamidia Hospital and Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre) in Bhopal vacated if first preference for admitting patients will be given to private hospitals? No other state is doing this. Is the government suggesting that it doesn’t have confidence in AIIMS or its own hospitals?”

A doctor at the government-run Hamidia hospital makes a similar point. “We were asked to make arrangements for COVID-19 patients but in over two weeks now, all we have done is screened patients for the virus. The hospital is empty because all patients are being sent to Chirayu. What is the rationale behind such a decision…the government will end up spending twice the money on private hospitals for the same treatment because it will not just have to pay the owners for treating patients but also for the period that the hospital will be a COVID-19 centre.”

For his part, Goenka of Chirayu praises the state government for its help and support. “I have 140 patients at Chirayu now,” he says, adding that the hospital’s total capacity is an impressive 800 beds. “I can accommodate 100 patients in the ICU and 32 in private rooms. We have 50 ventilators and can offer oxygen support to 400 more patients. The government has also promised us that we will have no shortage of medicines needed for the treatment, personal protective equipment (PPE) for all our staff and other necessary requirements,” he explains. The government has ordered that all COVID-19 patients receiving treatment in any hospital—private or government—will be covered under the Ayushman Bharat scheme, irrespective of their financial status. The agreement with Chirayu for treating COVID-19 patients, Goenka says, “is for a period of three months… the government will pay Chirayu for the treatment of all COVID-19 patients and compensate the hospital for the loss of its revenues during this period”.

Besides officials of the public health department, another major chunk of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Bhopal is of MP police personnel. Officially, the police have maintained that their personnel got infected “while tracking members of the Tablighi Jamaat who had come to the state after attending the event in Delhi’s Nizamuddin Markaz, where several cases of infection were later reported”. This explanation for widespread coronavirus infection within the police force may not be an exaggeration but it does raise another equally important question that betrays the state’s preparedness against the pandemic. “We knew that we were sending our men to track people who may have contracted the virus but we didn’t equip them with the protective gear needed for handling COVID-19 suspects. If we say that our men got the infection from the Jamaatis, we should also admit that we did not provide them with the necessary precautionary tools they desperately needed,” says a senior police officer who doesn’t wish to be named.

The outrage that the state administration’s mishandling of the crisis has generated, arguably, led Chouhan to issue an order, on April 10, which said that anyone sharing information related to the pandemic with the media for publication “without prior approval” of designated authorities will be “guilty of offences under the MP Epidemic Diseases Regulations, 2020”, and liable to legal action. The order was silent on whether media would be held liable for similar action if it publicised information that hadn’t been vetted by designated officials. Besides, it raised questions over whether, in the garb of curtailing spread of misinformation, the Chouhan administration wanted to force media to only share the government’s version. With new cases of coronavirus infection being reported from across the state every day and the threat of community transmission looming large after cases were reported in the interiors such as Sheopur, Morena, Sagar, Barwani, Chhindwara and Nagda, the challenge ahead for Chouhan’s administration won’t be limited to containing the pandemic in hotspots like Indore, Bhopal and Ujjain.

There’s another tough battle that’s round the corner for the administration running sans a council of ministers. The harvesting season has just begun and the state’s economy is not just predominantly agriculture-based but also rife with crop failure and resultant farmer distress. A major reason for the BJP losing power in the state 15 months ago was the Congress’s promise of farm loan waiver—the first two installments of which had been given, according to Kamal Nath, when the BJP toppled his government. With the 21-day lockdown extending for another fortnight (till May 3), Chouhan will have to find quick solutions to ensure that harvesting is not interrupted and farmers are able to sell their crop without the risk of amplifying the spread of the virus. Sources say Chouhan, like chief ministers of several agrarian states, has urged Prime Minister Narendra Modi to ease lockdown restrictions to ensure that harvesting crops, procurement and distribution are not hindered. While relaxation for farmers and the food distribution network are expected, the successful execution of this exercise would depend on the efficiency of respective state governments. The experience of the 21-day stay-at-home order in MP on this front has, so far, been disappointing.

“Besides disruption in the supply chain which all states have complained of, in various parts of MP, the district administration’s measures for transportation and distribution of vegetables were shoddy,” says Ram Bharose Kushwaha, a farmer who trades at the Karond Sabzi Mandi in Bhopal. “Since several localities in Bhopal were sealed, the municipal corporation said it would procure vegetables and then ensure proper delivery through its staff. Later, several corporation workers tested positive for the virus and for three-four days there was no supply of vegetables throughout Bhopal,” he says. If coronavirus cases continue to rise in the weeks ahead, such complications over procurement and supply of vegetables and food grain could become a recurring problem. Chouhan’s administration hasn’t yet offered any feasible alternative to the existing system, which has already been scarred by poor implementation.

The pandemic and the lockdown have also triggered massive reverse migration of the poor who had left their homes for work in big cities and are now compelled to journey back after losing jobs and whatever money they earned. In several MP districts—most prominently those that fall under the drought-prone Bundelkhand region—distress migration of debt-ridden farmers, who move to the cities to work as construction labour and daily wage earners, has been common for years. Now, hundreds of thousands of them are either back in their villages in MP or are marooned in camps across the country; detained by police while marching on foot from the states where they had found work. Chouhan is yet to announce any real financial relief package for these poor people. In the absence of a state budget there is also no specific allocation for relief measures arising.

In his hurry to return as chief minister, Chouhan may have created the biggest challenge of his political career for himself. And so far, the virus seems to be getting the better of him.

Tags