In November 1936, Basil Mathews asked M.K. Gandhi, “Where do you find the seat of authority?” Gandhi pointed to his breast, probably to the very same spot through which one of the bullets entered and lodged itself in his body, and replied, “It lies here. I exercise my judgement about every scripture, including the Gita.” What Gandhi was pointing out was what Socrates called his daimon/ daemon, his inner voice. If the inner voice or the conscience is the source of authority, it is the source of all judgement of truth; if it is the measure of things, then disobedience of what is repugnant to it becomes not only an imperative, but that capacity defines for such an individual the very idea of human vocation.

What Made Mahatma Gandhi The Supreme Artist Of Disobedience

For the Mahatma, the 'small, still voice' inside demanding disobedience can be acted upon only by submission to truth, writes author Tridip Suhrud

Gandhi was a supreme artist of disobedience. He disobeyed the empire, authorities of scriptures, injunctions of traditions, ‘laws’ of economic behaviour, gendered notions of work and action, even the political movement and party he led and helped shape. He disregarded the notion that politics was a zero sum game. His ashrams were nothing like the aranyaka of the ancient past, and his religion a radical disregard of rituals of worship. His quest for brahmacharya—as a mode of conduct that leads one to truth—led him to disobey not only the norms of being a grihastha—a householder—but also of the conduct expected of a brahmachari. His civil disobedience and non-violent resistance redefined the scope of ethical action in public life. Even on the question of non-violence, Gandhi pushed the notion to its limits by insisting at least in one instance that taking life could be an act of pure ahimsa.

And yet, Gandhi’s acts of disobedience required a submission, a fundamental submission. He had to submit to Satyanarayana—to Truth as God—and to the dweller within him, his antaryami, a voice that he beautifully described as a “small, still voice”. There were moments in his life when he felt that his submission was so total and complete that there was nothing he did himself, that he was being guided by the antaryami. He felt that he was closest to truth, and if not to truth, to that Upanishadic image of the golden lid that conceals truth, when his self-volition was minimal.

It is no contradiction for him that every act of disobedience requires a fundamental submission to truth and non-violence, and ideally to all the 11 vows—the Ekadash Vrata—of ashram life. The capacity and ability for disobedience accrues to one in the capacity for submission. The greater the capacity and willingness for submission, the higher the ability for disobedience of all forms, norms, structures and modes of conduct that impede the path to realisation of Swaraj—both as self-rule and as rule over the self—and the almost indistinguishable pair of truth and non-violence.

This is what gave limits to his disobedience, imbued his politics with spirituality such that it often perplexed his associates and, at times, left them infuriated. The roots of his self-practices that required a constant self-examination, self-censure, discipline—of body, mind, language, of food and possession—are cast in this ground. This ground is marked by an unyielding tautness that arose from a constant, unceasing play between disobedience and submission.

Thus, Gandhi’s life of disobedience is not a life of doubt. It is marked by a certainty of the divinity of truth, of the necessity of non-violence, and the capacity of the human person to realise both truth and perfect non-violence. All doubts were about his own capacity, his fitness for that truth—the darkness that surrounded him. Even during the darkest night of his soul, Gandhi did not doubt either the need or the possibility of satya and ahimsa.

And it was Gandhi who taught many Indians, and why just Indians, of his times—and dare I say, of our times—the art of disobedience. But we must remember—and we tend to forget just like our elders before us—that disobedience for Gandhi always had a preformative, a prefix: civil. This term attached to the stem of the word disobedience changed the very meaning and nature of disobedience and dissent. The idea of civil was not just about courtesy, good conduct with those one sought to oppose, but really about the right and true path—what he called sudhar. It is civility as sudhar that turned disobedience and dissent into civilisational possibility. Gandhi used the metaphor of music to explain this difference between ‘civil’ disobedience and disobedience. He said: “One great stumbling block is that we have neglected music. Music means rhythm, order.” It is the rhythm and order in politics that Gandhi craved.

Conscience is the source of dissent, asserts Gandhi. When something is repugnant to our conscience, we refuse to obey it. This disobedience is constituted by duty. It becomes our duty to disobey anything that is repugnant to our conscience. So doing, we become satyagrahis.

Disobedience as duty requires us to know ourselves, to recognise the supremacy of conscience, cultivate the art of listening to the “small, still voice” of the conscience, and submit to its dictates. “When it is night for all other beings, the disciplined soul is awake.” That’s how the Gita describes this state.

Disobedience or dissent, thus viewed, renders dissent a category and practice that is deeply personal. Its politics originates from its character as ‘Dharmya’. It demands obligatory obedience to a principle higher than self, politics and authority—scriptural and temporal. This kind of dissent has no pedagogy, in the sense of something capable of being taught by others. Dharmya disobedience is a practice. Despite its public nature, it remains within a deeply held and conserved private domain.

There is a widely held belief that while Gandhi advocated disobedience, he sought submission—at least from those closest to him. This assertion would not apply to his public life, his political activities. His ideas, methods and programmes were constantly challenged even within the Congress. Those who had great personal fondness for him—like Rabindranath Tagore and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru—constantly engaged him in public debates, often expressing their dismay at the man.

Jinnah was unwilling to grant that Gandhi was moved by a quest for truth. Dr B.R. Ambedkar was deeply pained, troubled and angry that Gandhi was unwilling and unable to see the truth of humiliation that varna and caste subjected the majority of human begins in the Hindu social order.

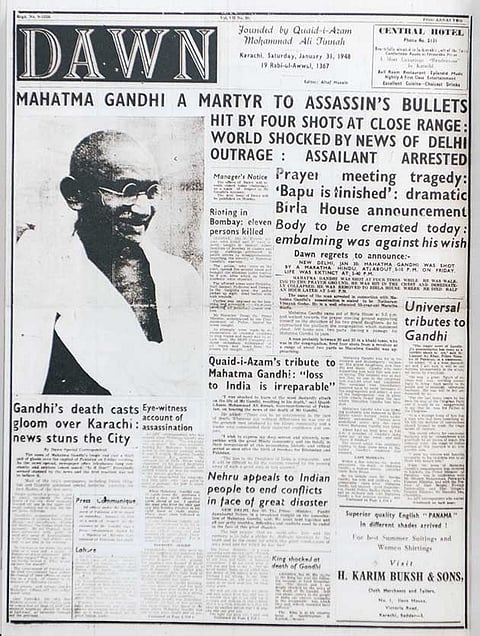

Nathuram Godse used this pistol to kill Gandhi in 1948.

But what of his ashrams? Harilal, his and Kasturba’s eldest son, remained from a very young age dissatisfied with his father’s insistence that his family could have no special claims over him or his work. Harilal’s disaffection was not just about his father’s conduct, but was about the very idea of the ashramic life constituted around the principle of aparigraha—voluntary poverty. He chose a different kind of poverty—a desolation corrosive for life. As his father gave himself up to Ramanama, Harilal surrendered to alcohol.

He occasionally appeared—unfailingly so at moments of grief—in Gandhi’s ashrams or the families of his siblings, only to disappear, in the words of Gopalkrishna Gandhi, “lured—it was assumed—by the subconscious pull of alcohol or by the memories of someone’s ‘kohl’ in a red-light district.” Harilal’s rebellion was not just against an unyielding father; it was a more fundamental one. Ramachandra Gandhi reminds us that his rebellion was against his father’s mistaken belief that god punishes our transgressions with recalcitrant sons.

Within the ashram community, while men seemed eager to follow Bapu in his experiments, women often challenged him. The ‘common kitchen’ experiment at the ashram had to be all but abandoned because most women, including Kasturba, were unwilling to give up the sanctity of their personal hearth—the only practice that probably allowed them to retain the idea of a family within the community of the ashram. The women also refused to accept that the idea of aparigraha required them to give up all personal wealth, especially their ‘stree dhan’. In both INStances, Gandhi had to yield and amend the ashramic conduct.

The ashram community was also capable of challenging Gandhi’s conduct and dissociating from him when their conscience found it repugnant. Kishorelal Mashruwala, whose niece Sushila was married to Manilal Gandhi, was so deeply perturbed by Gandhi’s inability to see that his brahmacharya experiment in 1947 was ab initio false that he withdrew from the editorship of Harijan journal.

Not all acts of disobedience have to be politically charged. Gandhi was capable of breaking ashramic rules much to the consternation of his co-inhabitants—like keeping packs of imported cigarettes for Jawaharlal that Gandhi had received as a Christmas present.

Tridip Suhrud Author of a critical edition of Gandhi’s Autobiography and an English rendering of The Diary of Manu Gandhi

Tags