What do you call climate change in the language of the Warlis, an artistically inclined indigenous community residing along the North Maharashtra-Gujarat border.

What Do You Call Climate Change In Warli Language?

Western India’s Warli tribe faces shifting diets and lifestyles amid climate change and urbanisation. A new initiative, that includes a climate change dictionary, documents experiences of indigenous tribal and marginalised communities to inform government policymakers, bridging gaps between local realities and global climate strategies

The question was articulated during a recent gaav samvaad (village dialogue) exercise among Warli tribe members of Nagave, Sonave and Darshet villages of Saphale in the Palghar district on the outskirts of Mumbai.

Renowned globally for their human and animal stick figure artwork and the Tarpa dance, Warlis draw their sustenance and livelihood from rice farming and forest produce.

After several rounds of attempted explanations about climate change and its innate linkages to changes in weather and environment, 62-year-old Surekha Karela had a eureka moment.

“Jevha jaul padte tevha sagla kharab hote. Sheti la keed padte, bhaji karpun jaate (Those days destroy everything, the farm crops have worms and vegetables get burned),” Karela said, trying to link the climate change phenomenon to more relatable elements encountered by the Warlis in their daily lives. Karela’s reply emboldened Shantaram Mahadya Ghatal, a village elder, to prompt: “Jevha jaul padte, tevha aamhi baher jaat nahi, lahan porana pan pathvat nahi. (We do not step out in such weather and don’t send our little children outdoors.)”

During the rural dialogue initiative organised by non-profits Asar Social Impact Advisors, working on climate change and Resource and Support Centre for Development (RSCD), involved in capacity building of female elected representatives, villagers learned to link climate change to the recurring bouts of extreme heat and humidity, which make people sick and destroy crops. Elders over sixty, referred to this uncomfortable weather as jaul, pronounced as ja-ool.

Climate change has no word or equivalent in the language of Warlis. But the Indigenous tribe residing in the deep forests and hills on the northern outskirts of Mumbai, bordering Gujarat, has known its effects and experienced the shifts in nature firsthand.

In the past, jaul occurred at the end of the monsoon season in September and October. Similar to Mumbai's more urban phenomenon of ‘October heat,’ this excessive spell of humidity now extends unseasonably into November. Winter days are fewer, temperatures lack chill, rains are erratic, and several species of berries, medicinal plants, and wood have vanished. Karvi bamboo, essential for housing among the Warli and Katkari tribes, too, is now scarce, villagers said.

These conversations through gaav samvaad, on the everyday experiences of Warlis, who are one hundred percent dependent on forests, now feature in a novel, in-the-works dictionary on climate change that documents shifts in climate and its impacts in local ways across Maharashtra’s diverse regions. The pioneering initiative crucially attempts to fill the gap between the policymakers sitting in Mumbai drafting climate change reports, and the people on the margins experiencing climate change.

Indigenous words like havaman (weather) or varapoi, paryavaran (environment) or geda gutta, dushkaal (drought) or bhum mudada, perni (sowing) or pererach, jeval (meal) or kunda tagne, van utpann (forest produce) or jungleoj maal, among many others, now find articulation in the work-in-progress, unique lexicographical exercise.

Words related to the environment and climate spoken by the Warli, Madiya, and Bhil tribals of Maharashtra aren't found in school textbooks or government records. However, these everyday terms, used in Nandurbar, Gadchiroli, and Palghar to denote weather changes, were recorded during the various gaav samvaad meetings and are now part of a climate change repository documenting the experiences of high-risk vulnerable communities in Maharashtra.

Neha Saigal, director, gender and climate at Asar, observed that conversations on climate change in the policy circles were far from existing ground realities. Reports on climate were gender blind and climate initiatives often left out women and marginalised communities from the discussion, she said.

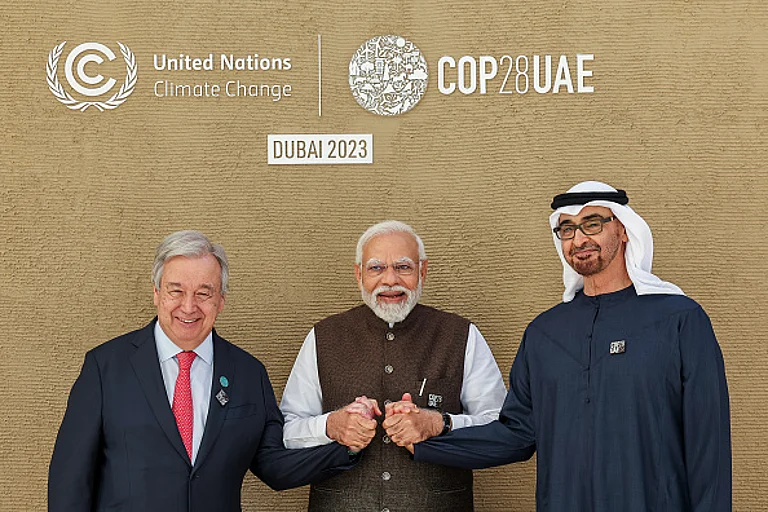

“The language and experiences on climate and climate change are Westernised. We realised that even the United Nation’s (UN) climate change dictionary does not have the words or the explanation of concepts in the language of marginalised communities, nor did it include the lived experiences of women at the grassroots and how they were facing the crisis in their everyday life,” Saigal claimed.

The new repository, she added, culled from the content of nearly 5,000 interviews with local villagers through gaav samvaad meetings, will help policymakers in the government and public sector implement policies that reflect the experiences from the ground.

The initiative documents villagers’ experiences along eight main themes: water, forests, land, biodiversity, animals, energy, village fairs, heritage and injuries. Ankita Bhakhande of ASAR noted that these parameters helped villagers recount climate shifts. Older villagers and women particularly highlighted extreme heat, unseasonal rainfall, and the disappearance of flora and fauna.

The Maharashtra repository documents climate change impacts. They conducted 250 village dialogues with women, farmers, youth, children, and tribals across Maharashtra’s ten districts in Konkan, Vidarbha, Marathwada and Nashik region. With 50 trainers and paryavaran sakhis (friends of the environment), they record local experiences, perceptions, and terms related to climate shifts.

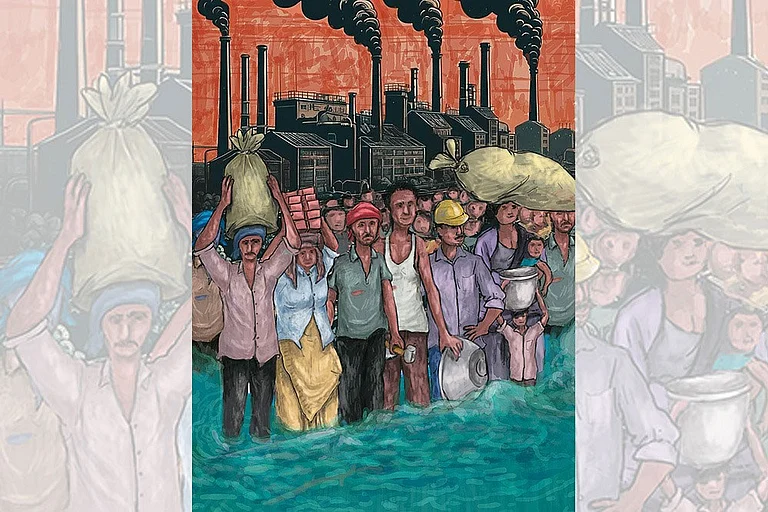

In Adivasi villages of Palghar and Nandurbar, reliance on retail markets has increased as forest produce and traditional livelihood earnings decline. In Gadchiroli, respondents noted forest degradation from soil erosion, unseasonal rainfall, and development. Women in Nagpur highlighted frequent water scarcity with the saying, “mhadyavar handa dhokyachi ghanta (a pot over the head is a sign of danger)”.

Women in drought-prone Marathwada's Osmanabad and Beed districts reported worsening climate, rapidly depleting ponds and wells, and mono farming of sugarcane, reducing groundwater and soil quality. Respondents across ten regions lamented agriculture's decline, water scarcity and unpredictable weather forcing migration. Erratic weather also impacted village fairs, traditionally held around sowing and harvesting seasons.

Saigal found the cultural impact of climate change disturbing and one that rarely figured in discussions. “When we saw that many respondents spoke about the fairs, rituals and traditions associated with forest produce, we realised that climate change was affecting culture. The entire culture of several communities was changing, and they were moving the traditional dates of the days to a later period. This was shocking.”

In Palghar, paryavaran sakhi Ujjwala Jadhav and trainer Trupti Patil also noted a shift in the Warli villagers' food traditions. During Diwali, they prepare a sweet cucumber bhakri (coarse bread) steamed in chai cha paan leaves, valued for their aroma. Warlis avoid water-rich vegetables during rains, resuming consumption post-monsoon.

“In the past, we would go inside forest areas to collect the leaves for steaming bhakris, but the plant is now rarely found,” said Yamuna Govind Dhodhadi, a respondent from Sonave village. “For many years, we have used another leaf. We steam the bhakri using rui chai paan (Calotropis gigantea), but the bhakri doesn’t have the same taste.”

The Warli tribe’s diet and lifestyle have shifted due to reduced forest produce, climate change, and urbanisation. Findings from village dialogues will be compiled into a handbook for the Maharashtra government. Saigal said, the exercise aims to inform policymakers on climate strategies and budgeting for local adaptive measures. The data can strengthen biodiversity committees, train government cadres, and work with local paryavaran sakhis for climate-adapted programmes.

With climate shifts occurring more frequently, Jadhav emphasised the importance of educating vulnerable tribes like the Warlis about climate change impacts to prepare for the future. Jadhav and Patil spent hours extracting information and establishing communication with the shy tribe members, who often avoid strangers coming from urban spaces. They learned the importance of documenting traditional knowledge of lost and nearly extinct natural resources, traditions, and practices, as it holds the key to future conservation.

“Warlis existence depends upon nature and tribes like theirs are the first to be affected by climate change. They are also like the last link connecting the fast-disappearing old world and the new one. We need to learn about nature from them so we can know what to preserve,” Jadhav said.