On Greatness

We bestow ‘greatness’ easily in India. What makes a person great, do we really need great people, and drawing a lakshmanrekha for it in every life.

In our day-to-day social and professional conversations we tend to overuse, trivialise and devalue the word ‘great’ to the point of parody. It seems everything, or almost everything, has an in-built potential for greatness. An ice-cream can be great, a square-cut can be great, a barber can be great, a hotel can be great, a magician can be great. So, as we commence our detailed examination of what constitutes greatness, we need to move from the ridiculous to the sublime.

But first, a warning. Great individuals, who acquire the rare virtue by one of the three routes suggested by Shakespeare, must be rigorously evaluated, subjecting them to an appraisal which is at once exhaustive and unsparing.

The devil, as we all know, lies in the detail. Someone classified as a great human being, naturally, needs to be inspirational, a role model, someone who through his or her genius communicates pleasure, pride and enjoyment to millions. The phrase ‘national treasure’ should sit easily on the person.

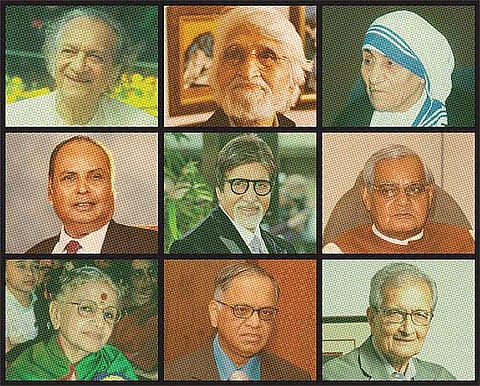

Take someone like Lata Mangeshkar or Sachin Tendulkar or M.S. Subbulakshmi. On the pleasure scale, all three qualify comfortably. On the inspirational scale and the role model scale too they qualify comfortably. But Sachin and Lata (Satyajit Ray, Ravi Shankar, M.F. Husain and Amitabh Bachchan are others), who otherwise seem to have all the right qualifications to walk into the pantheon of the great, lack one essential characteristic. To be indubitably great, the individual needs to go beyond the aforementioned three scales. He or she must in some measure have contributed to improving the life of the common man.

In India, especially, making lives materially (as opposed to emotionally or spiritually) better is crucial because vast numbers of our fellow citizens live in degrading poverty. If you are sick or hungry or destitute, watching Sachin Tendulkar score a scintillating century or hearing Lata Mangeshkar sing a lilting melody may provide short-term but not long-term relief. It will not fill an empty stomach. Compassion, too, is not enough. Mother Teresa won a Nobel prize for making available institutionalised compassion to those abandoned and forsaken on the filthy streets of Calcutta. She made sure they got a dignified death. Alas, she couldn’t prevent them from dying, she could not lift them from hopelessness and despair. Mother Teresa, for all her goodness, couldn’t transform lives, she could only offer a few days or hours of solace. She did good work but not great work.

The acid test for greatness, in India, must inevitably entail some degree of enabling of economic and social enhancement—or at least point the way to how it can be obtained. Think of Ela Bhatt, who seems to be a particular favourite of Hillary Clinton.

Consequently, all the men and women who led India’s struggle against colonialism automatically qualify for the coveted label. They didn’t just liberate a large nation from the colonial yoke, but through that liberation allowed the citizen an opportunity to explore and aspire for an improved quality of life. (Of course, if you believe that life under the British was superior and preferable to the one we are living now, no argument is possible.) Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, Ambedkar, Azad, without putting them into any sort of hierarchy, walk into the pantheon under discussion without any difficulty.

Some of the other names which come into the reckoning while compiling such a list—Ravi Shankar, Satyajit Ray etc—unfortunately fall at the last hurdle because the critical component of betterment is missing, or present in a minimal degree in their bio-data. J.R.D. Tata, in my view, is a borderline case since he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Undoubtedly, he enhanced the business empire he inherited but he did not create it. Similarly, Ratan Tata took forward what had already been started. Dhirubhai Ambani, who began life as a petrol pump attendant, and Narayana Murthy, who heralded India’s software revolution, achieved greatness through the old-fashioned path of blood, sweat and tears. They have better claims to greatness.

In times of grave national challenge, a country can throw up great leaders (like Winston Churchill in Britain during World War II). The relevant leaders may demonstrate exceptional courage, strategic brilliance and organisational skill in combating and overcoming the specific challenge. However, once the moment has passed, the challenge negotiated, he or she fades away. Churchill was emphatically rejected by the British after Germany surrendered in 1946. Jayaprakash Narayan, during the Emergency in 1975 and just after, managed to unite an impossibly fractious opposition to defeat Indira Gandhi in 1977, but achieved little else.

One can argue, nevertheless, that in a young and emerging democracy impoverished by raiders, conquerors and foreign dynasties for centuries, and in present times governed by the corrupt and the incompetent, there is some requirement for a few great men and women. However, the sooner the requirement is dispensed with, the better it will be for that country.

A couple of weeks ago, on a hot Sunday afternoon, I spent time with the flawed but well-meaning Anna Hazare. I couldn’t help notice in a crowd of around 8,000 the conspicuous absence of your usual metropolitan cynicism. Family after family waving the national flag lustily and wearing ‘I am Anna’ topis came to see and pay awed obeisance to the great man who promised to rid India of corruption. For me it was an instructive afternoon.

Perhaps, a few great men are needed, but not too many. With one caveat: we must be able to distinguish between the bogus and the genuine. Credulity, of which there is no shortage in our society, poses a major problem. Periodically, we are duped into accepting that so-and-so is great, a messiah, saviour only to be disillusioned sooner rather than later. If you ask me, I would have some difficulty in identifying any political figure after Jawaharlal Nehru who can be bestowed the crown of greatness.

Just consider. Which are the most settled, harmonious, gender-fair, affluent and egalitarian countries on our planet? Immediately, the Scandinavian quartet of Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland come to mind. Belgium, Holland, Canada, Switzerland do not lag far behind. Now think how many Great Men and Women they have thrown up? Olof Palme and Dag Hammarskjold from Sweden are the only ones I can recall. (Sample this rather cruel joke: how many famous Belgians can you think of? The fictional character, Hercule Poirot, created by an Englishwoman, Agatha Christie, topped the list in a BBC poll.) The poor Swiss have been lampooned for decades, by among others, Orson Welles, for being capable of producing only cuckoo-clocks and chocolates. However, an independent-minded person will be forced to concede that these nations have not done too badly without the benefit of great men to guide them.

Any hope for you and me? Do we have an iota of chance for aspiring to greatness? Or doing great things? I am referring to the man on the Chandni Chowk bus. Is he perpetually reduced to being an also-ran? Can he only watch, mostly in disgust, as his so-called great men screw up his country? Is the aam aadmi reduced to being just an impotent spectator?

The situation is not wholly hopeless. The common man can also be a competitor in the greatness race. But we have to set different norms which are as, if not more, important than those we set to evaluate conventional greatness. Since it is a given that the man on the Chandni Chowk bus does not possess the tools to do great things (like being elected prime minister), he can aim for mini-greatness, which collectively could make more of a difference than the momentous deeds of great men. Here is my inventory for mini-greatness: pay your taxes, obey the laws of the land, do not covet your neighbour’s wife, be an upstanding member of the community, shun caste, regional, religious and ethnic biases. Of course, this is a less neon-lit kind of greatness or mini-greatness. But it counts.

In this quest you will have to draw a lakshmanrekha. Your conscience will tell you where that line is.

Tags