Like the railways, electricity, and the theory of evolution, nationalism was also invented in modern Europe. The European model of nationalism sought to unite residents of a particular geographical territory on the basis of a single language, a shared religion, and a common enemy. So to be British, you had to speak English, and minority tongues such as Welsh and Gaelic were either suppressed or disregarded. To be properly British you had to be Protestant, which is why the king was also the head of the Church, and Catholics were distinctly second-class citizens. Finally, to be authentically and loyally British, you had to detest France.

Patriotism Vs Jingoism

Gandhian nationalism, enshrined in the Constitution, is based on ideals of equality and diversity. As a new pretender, with its hate-filled credo, tries to supplant it, our duty is to put up a dogged fight.

Read Also

- Happy R-Day! by Rajesh Ramachandran

- A Nation Within 4 Temples by S. Gurumurthy

- From Amir Khusrau To Filthy Abuse by Irfan Habib

- Don’t Foist Fear Onto Nationalism by C.K. Saji Narayanan

- 30-01-1948 by Apoorvanand

- Rockbed Of Cultural Renascence by Dr R. Balashankar

- Gandhi Smriti Diary by Brij Pal and Vishnu Prasad

Now, if we go across the Channel and look at the history of the consolidation of the French nation in the 18th and 19th centuries, we see the same process at work, albeit in reverse. Citizens had to speak the same language, in this case French, so the dialects spoken in regions like Normandy and Brittany were sledgehammered into a single standardised tongue. The test of nationhood was allegiance to one language, French, and also to one religion, Catholicism. So Protestants were persecuted. Likewise, French nationalism was consolidated by identifying a major enemy; although who this enemy was varied from time to time. In some decades the principal adversary was Britain; in other decades, Germany. In either case, the hatred of another nation was vital to affirming faith in one’s own nation.

This model—of a single language, a shared religion, and a common enemy—is the model by which nations were created throughout Europe. And it so happens that the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is in this respect a perfect European nation. Mohammad Ali Jinnah insisted that Muslims could not live with Hindus, so they needed their own homeland. After his nation was created, Jinnah visited its eastern wing and told its Bengali residents they must learn to speak Urdu, which to him was the language of Pakistan. And, of course, hatred of India has been intrinsic to the idea of Pakistan since its inception.

Indian nationalism, however, radically departed from the European template. The greatness of the leaders of our freedom struggle—and Mahatma Gandhi in particular—was that they refused to identify nationalism with a single religion. They further refused to identify nationalism with a particular language and even more remarkably, they refused to hate their rulers, the British.

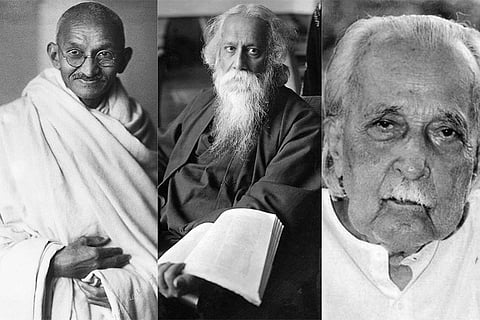

Gandhi, Tagore and Kota Shivaram Karanth chose plurality/equality as the vehicles for patriotism

Gandhi lived and died for Hindu-Muslim harmony. He emphasised the fact that his party, the Indian National Congress, had presidents who were Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Parsi. Nor was Gandhi’s nationalism defined by language. As early as the 1920s, Gandhi pledged that when India became independent, every major linguistic group would have its own province. And perhaps the most radical aspect of the Indian model of nationalism was that you did not even have to hate the British. Indian patriots detested British imperialism, they wanted the Raj out, they wanted to reclaim this country for its residents. But they could do so non-violently, and they could do so while befriending individual Britons (Gandhi’s closest friend was the English priest C.F. Andrews). Further, they could get the British to ‘Quit India’ while retaining the best of British institutions. An impartial judiciary, parliamentary democracy, the English language, and not least the game of cricket; these are all aspects of British culture that we kept after they had left.

British, French and Pakistani nationalism were based on paranoia, on the belief that all citizens must speak the same language, adhere to the same faith, and hate the same enemy. On the other hand, Indian nationalism was based on a common set of values. During the non-cooperation movement of 1920-21, people all across India came out into the streets, gave up jobs and titles, left their colleges, courted arrest. For the first time, the people of India had the sense, the expectation, the confidence that they could create their own nation. In 1921, when non-cooperation was at its height, Gandhi defined Swaraj as a bed with four sturdy bed-posts. The four posts that held up Swaraj were non-violence, Hindu-Muslim harmony, the abolition of untouchability and economic self-reliance. Three decades later, after India was finally free, these values were enshrined in our Constitution.

When the Republic of India was created, its citizens were sought to be united on a set of values: democracy, religious and linguistic pluralism, caste and gender equality and the removal of poverty and discrimination. They were not sought to be united on the basis of a single religion, a shared faith, or a common enemy. Now this is the founding model of Indian nationalism, which I shall call ‘constitutional patriotism’, because it is enshrined in our Constitution. Let me identify its fundamental features.

The first feature of constitutional patriotism is the acknowledgement and appreciation of our inherited and shared diversity. In any major gathering in a major city—say in a music concert or in a cricket match—people who compose the ‘crowd’ carry different names, wear different clothes, eat different kinds of food, worship different gods (or no god at all), speak different languages, and fall in love with different kinds of people. They are a microcosm not just of what India is, but of what its founders wished it to be. For, the founders of the Republic had the ability (and desire) to endorse and emphasise our diversity. As Rabindranath Tagore once said about our country: “No one knows at whose call so many streams of men flowed in restless tides from places unknown and were lost in one sea: here Aryan and non-Aryan, Dravidian, Chinese, the bands of Saka and the Hunas and Pathan and Mogul, have become combined in one body”.

A second quote underlining the extraordinary richness of the mosaic that is India comes from the Kannada Tagore, Kota Shivaram Karanth. Karanth had heard demagogues speak of something called ‘Aryan culture’. Did they realise, he asked, “what transformations this ‘Aryan culture’ has undergone after reaching India?”. In Karanth’s opinion, “Indian culture today is so varied as to be called ‘cultures’.” The roots of this culture go back to ancient times: and it has developed through contact with many races and peoples. Hence, among its many ingredients, it is impossible to say surely what is native and what is alien, what is borrowed out of love and what has been imposed by force. If “we view Indian culture thus”, said Karanth, “we realise that there is no place for chauvinism”.

Now, an appreciation of this diversity means that we understand that no type of Indian is superior or special because they belong to a particular religious tradition or because they speak a certain language. In 19th century England, Protestants were superior to Catholics, English speakers were superior to Welsh speakers. In 20th century India, patriotism was defined by the allegiance to the values of the Constitution, not by birth, blood, language or faith.

The second feature of constitutional patriotism is that it operates at many levels. Like charity, it begins at home. It is not just worshipping the national flag that makes you a patriot. It is how you deal with your neighbours and your neighbourhood, how you relate to your city, how you relate to your state. In America, which is professedly one of the most patriotic countries in the world, every state has its own flag. And some states of India also have their own flag, albeit informally. Every November, when Rajyotsava Day is celebrated in Karnataka, a red-and-yellow flag is unfurled in many parts of the state. It is not Anglicised upper-class elites like this writer who display this flag of Karnataka, but shopkeepers, farmers, and autorickshaw drivers.

Patriotism can operate at multiple levels. The Bangalore Literary Festival (which is not sponsored by shady corporates, but is crowd-funded) is an example of civic patriotism. The red-and-yellow flag of Karnataka is an example of provincial patriotism. Cheering for the Indian cricket team is an example of national patriotism. So, patriotism can operate at more than one level—the locality, the city, the province and the nation. A broad-minded (as distinct from paranoid) patriot recognises that these layered affiliations can be harmonious, complementary and reinforce one another.

The model of patriotism advocated by Gandhi and Tagore was not centralised, but disaggregated. And it has helped make India a diverse and united nation. Look at what is happening in Spain today. Why have the Catalans rebelled? Because they weren’t given the space and the freedom to honourably have their own language and culture. And the centralised Spanish state came down so hard that the Catalans had a referendum in which many of them said, ‘we want independence’. Had the Republic of Spain been founded and run on Indian principles, this would not have happened. Had Pakistan not imposed Urdu on Bengalis, they may not have split in two nations a mere quarter-of-a-century after Independence. Had Sri Lanka not imposed Sinhala on the Tamils they would not have had thirty years of ethnic strife. India has escaped civil war and secession because its founders wisely did not impose a single religion or single language on its citizens.

One can be a patriot of Bangalore, Karnataka, and India—all at the same time. But the notion of a world citizen is false. The British-born Indian J.B.S. Haldane put it this way: “One of the chief duties of a citizen is to be a nuisance to the government of his state. As there is no world state, I cannot do this.... On the other hand I can be, and am, a nuisance to the government of India, which has the merit of permitting a good deal of criticism, though it reacts to it rather slowly. I also happen to be proud of being a citizen of India, which is a lot more diverse than Europe, let alone the US, USSR or China, and thus a better model for a possible world organisation. It may, of course, break up, but it is a wonderful experiment. So I want to be labelled as a citizen of India”.

A citizen of India can vote in panchayat, assembly and parliamentary polls; he or she can make demands on their local sarpanch, MLA, or MP. In between elections he or she can affirm their citizenship (at all these levels) through speech and (non-violent) action. But global citizenship is a mirage; or a cop-out. Those who cannot or will not identify with locality, province or nation accord themselves the fanciful and fraudulent title of ‘citizen of the world’.

The third feature of constitutional patriotism, and this again comes from people like Gandhi and Tagore, is the recognition that no state, no nation, no religion or no culture is perfect or flawless. India is not superior to America necessarily, nor is America superior to India necessarily. Hinduism is not superior to Christianity necessarily, nor is Islam superior to Judaism necessarily. Religious and ideological fundamentalists are possessed by the idea of superiority. They believe that they and only they have the perfect truth.

But no state, no religion, is perfect or flawless. And no leader either. The great B.R. Ambedkar, in his last speech to the Constituent Assembly, said that “in India, Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship”.

Ambedkar’s warning was prophetic. It anticipated the rule, or rather the misrule, of Indira Gandhi, which came about only because her bhakts placed their liberties at her feet. And now, Modi bhakts are blindly worshipping our present prime minister. In truth, this cult of the great leader which Ambedkar warned against bedevils not only Indian politics, but also Indian corporate and intellectual life, even Indian cricket.

Gandhi himself once admitted to making a Himalayan blunder. But I cannot recall Narendra Modi acknowledging even a minor mistake. However, it is very important that citizens recognise that like nations and cultures, leaders are not perfect or infallible either.

The central figure in the dynasty that has captured Congress

A fourth feature of constitutional patriotism is this: we must have the ability to feel shame at the failures of our state and society, and we must have the desire and the will to correct them. The most gross and debased aspects of Indian culture and society are discrimination against women and against Dalits. And a true patriot must feel shame about them. Gandhi felt shame, Ambedkar felt shame, Nehru felt shame, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay felt shame. That is why in our Constitution we abolished caste and gender distinctions. Yet these distinctions pervade everyday life. Unless we continue to feel shame, and act accordingly, they will continue to persist.

The fifth feature of constitutional patriotism is the ability to be rooted in one’s culture while being willing to learn from other cultures and countries. This too must operate at all levels. If you live in Basavanagudi, love Basavangudi, but think what you can learn from Jayanagar or Richmond Town. Love Bangalore but think what you can learn from Chennai or Hyderabad. Love Karnataka, but think what you can learn from Kerala or Himachal Pradesh. Love India, but think of what you can learn from Sweden or Canada. So, true patriots must be rooted in their locality, their state, their country but have the recognition and the understanding that they can learn from other cultures, other cities, other countries who have done some things better than them.

Two quotes, from the greatest of modern Indians, illustrate this open-minded patriotism very well. Thus Tagore wrote in 1908: “If India had been deprived of touch with the West, she would have lacked an element essential for her attainment of perfection. Europe now has her lamp ablaze. We must light our torches at its wick and make a fresh start on the highway of time. That our forefathers, three thousand years ago, had finished extracting all that was of value from the universe, is not a worthy thought. We are not so unfortunate, nor the universe so poor”.

Thirty years later, Gandhi remarked: “In this age, when distances have been obliterated, no nation can afford to imitate the frog in the well. Sometimes it is refreshing to see ourselves as others see us”.

As a patriotic Indian, I am delighted that the West has acknowledged the importance and value of yoga. Likewise, there must be many aspects of life in the West, in Africa, in China and Japan that we can acknowledge, appreciate, learn from. As Tagore suggested, we must find glory in the illumination of a lamp lit anywhere in the world.

An appreciation of individual and cultural diversity; a readiness to enact one’s citizenship at different levels; the recognition that no religion, nation, or leader is flawless; the ability to feel shame at the crimes of one’s religion, state, society or nation; the willingness to learn from other countries—these, to me, are the five founding features of the model of patriotism bequeathed us by the nation’s founders. This model is now in tatters. It is increasingly being replaced by a new model of nationalism, which privileges a single religion, Hinduism, which argues that a real Indian is a Hindu. This new model also privileges a single language—Hindi. It insists that Hindi is the national language, and whatever the language of your home, your street, your state, you must speak Hindi also. Thirdly, this model privileges a common external enemy—Pakistan.

Whether they acknowledge it or not, those promoting this new model of Indian nationalism are borrowing (and more or less wholesale) from 19th century Europe. However, to the template of a single religion, a single language and a common enemy they have added an innovation of their own—the branding of all critics of their Party and their Leader as ‘anti-national’. This scapegoating comes straight from the holy book of the RSS, M.S. Golwalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts. In this book, Golwalkar identified three ‘internal threats’ to the nation—Muslims, Christians and Communists. Now, I am not a Muslim, Christian or Communist, but I have nonetheless become an enemy of the nation. Because any critic, any dissenter, anyone who upholds the old ideal of constitutional patriotism is considered by those in power and their cheerleaders to be an enemy of the nation.

In the wonderful film Newton, one character says, “Ye desh danda aur jhanda se chalta hai”. This line beautifully captures the essence of a paranoid and punitive form of nationalism, based on a blind worship of the (sole and solitary) Flag, and the use of the stick to harass those who do not follow or obey you. This new nationalism in India is harsh, hostile, and unforgiving. The name by which it should be known is certainly not ‘patriotism’, and not even ‘nationalism’. Rather, it should be called jingoism.

The dictionary defines a patriot as ‘a person who loves his or her country, esp. one who is ready to support its freedoms and rights and to defend it against enemies or detractors’. Note the order; love of country first, support of freedom and rights second, and defence against enemies last. And what is the dictionary definition of jingoist? One ‘who brags of his country’s preparedness for fight, and generally advocates or favours a bellicose policy in dealing with foreign powers; a blustering or blatant ‘patriot’; a Chauvinist’. The order is reversed: first, boasting of the greatness of one’s country; then advocating attacking other countries. No talk of rights or freedom, or love either.

The dictionary also has some representative quotes. Thus the 18th century Irish philosopher George Berkeley defined a patriot as “one who heartily wisheth the public prosperity, and doth...also study and endeavour to promote it”. The patriot wishes above all to promote welfare and happiness. On the other hand, the Gentleman’s Magazine said in 1881 that “the jingo is the aggregation of the bully. An individual may be a bully; but, in order to create Jingoism, there must be a crowd”. This is so appropriate to our country and our time. For, while Arnab Goswami is a bully, it is his audience which creates and sustains jingoism.

Patriotism and jingoism are two distinct, different, opposed varieties of nationalism. Patriotism is suffused with love and understanding. Jingoism is motivated by hate and revenge. Thus the Pall Mall Gazette in 1885: “The essential infamy of Jingoism was its assertion as the first law of its being that might was right.” Danda aur Jhanda; that is the sum and substance of jingoism, whose Indian variant goes by the name of ‘Hindutva’.

I have already outlined the founding features of patriotism. What are the founding features of jingoism? First, the belief that one’s religion, culture and nation and leader are perfect and infallible. Second, the demonising of critics as anti-nationals and deshdrohis. Third, violence and lumpenisation, not just abusing your critics but harassing and intimidating them, through the force of the state’s investigating agencies and through vigilante armies if required.

I am a citizen, but also a scholar, so I must explain not just what distinguishes patriotism from jingoism but why jingoism is on the ascendant today. Why is it that the hardline Hindutvawadi has so many supporters? Why is it that Times Now and Republic, Aaj Tak and Zee News command higher viewership than their competitors?

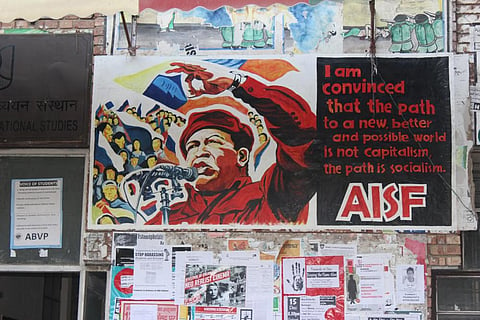

I believe there are four major reasons why jingoism is on the ascendant, while constitutional patriotism is on the retreat. The first is the hostility to our national traditions of the Indian Left. The Communist parties, particularly the CPI(M), are an important political force in India. They have been in power in several states. Their supporters have historically dominated some of our best universities, and been prominent in theatre, art, literature and film. But the Indian Left, sadly and tragically, is an anti-patriotic Left. It has always loved another country more than their own.

The country our Communists were devoted to used to be the Soviet Union, which is why they opposed the Quit India Movement, and launched an armed insurrection on Stalin’s orders immediately after Gandhiji was murdered. Later, the country the Communists loved more than India was China; so, in 1962, they refused to take their homeland’s side in the border war of that year. In the same decade, the Naxalites sprung to action shouting, ‘China’s Chairman is our Chairman’. Still later, when the Communists became disillusioned with both Soviet Union and China, they pinned their faith on Vietnam. When Vietnam failed them, it became Cuba; when Cuba failed them, it became Albania.

When I was a student in Delhi University, there was a Marxist professor who thought Enver Hoxha was a greater thinker than Mahatma Gandhi. But then Albania failed too. So now, Venezuela became the foreign country our comrades loved more than India. Consider thus the extraordinary veneration among the Indian Left for the late (but by me unlamented) Hugo Chavez. If you think Narendra Modi is authoritarian, then Hugo Chavez was Narendra Modi on steroids. The megalomaniac Chavez destroyed the Venezuelan economy and Venezuelan democracy, and yet he was worshipped in JNU and by Indian Leftists elsewhere too.

Some months ago, I met a prominent CPI(M) intellectual, a historian like myself, but unlike me a party man. Since he is, by the standards of his tribe, reasonably open-minded, I offered him an unsolicited suggestion. I said, why don’t you put Bhagat Singh’s portrait up at your party conferences? How can you allow a professed Marxist to be appropriated by the Hindutvawadis? As it happens, in the conferences of the CPI(M) there are only four portraits displayed. All are men. None are Indian; none are alive. The dead white men our Communists publicly venerate are two German intellectuals—Marx and Engels, and two Russian tyrants—Lenin and Stalin. So I told this Communist historian, at least have Bhagat Singh’s portrait at your party conferences, for he was a Marxist, and he was Indian. The historian said, without much hope or conviction, that he would put the proposal up to the party leadership to consider.

The anti-patriotism of the Indian Left is the first reason that jingoism is on the ascendant. The second reason is the corruption of the Congress Party, the tragedy by which the great party which led our freedom movement has been captured by a single family. I have spoken of how the Left chooses its icons, but in some ways the Congress is even worse. When the UPA was in power, it named everything in sight after a Nehru-Gandhi. Why couldn’t the new Hyderabad international airport have been named after the Telugu composer Thygaraja or the Andhra patriot T. Prakasam? Why Rajiv Gandhi? Likewise, when the new sea link in Mumbai had to be given a name, why couldn’t the UPA consider Gokhale, Tilak, Chavan or some other great Maharashtrian Congressman? Why Rajiv Gandhi again?

Many, indeed most, of the icons of the national movement belonged to the Congress party. But the Congress has abandoned and thrown them away because it is only Nehru, Indira, Rajiv, Sonia, and now Rahul that matter to them. (The only great, dead, Congressman outside the family they are willing to acknowledge is Mahatma Gandhi, because even they can’t obliterate him from their party’s history.) Gopalkrishna Gandhi, who is one of the wisest and most patriotic Indians alive, once said, in a moment of sad reflection: “It is because the Congress has disowned Patel that the BJP has been able to misown Patel”. Tragically, Sonia’s and Rahul’s Congress have also disowned Shastri, Kamaraj, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Jagjivan Ram, Narasimha Rao and many, many, others.

If Hugo Chavez gets a more rousing welcome in JNU than any Indian, then obviously this will help the jingoists. Likewise, if the UPA Government named all major schemes after a single family, ignoring even the great Congress patriots of the past, then that would give a handle to the jingoists, too. The corrupt, chamchagiri culture of the Congress Party is a disgrace. When I made a sarcastic remark on Twitter about Rahul Gandhi becoming Congress president, someone put up a chart listing the presidents of the BJP since 1998—Bangaru Laxman, Jana Krishnamurthi, L.K. Advani, Rajnath Singh, etc., the last name on the list being Amit Shah, followed by ‘party worker’. Whereas the presidents of the Congress in the same period were ‘Sonia Gandhi, Sonia Gandhi, Sonia Gandhi...Rahul Gandhi....’

A third reason for the rise of jingoism is that it is a global phenomena, manifest in the rise of Trump, Brexit, Marine Le Pen, Erdogan, Putin etc, all of whom puruse a xenophobic, paranoid, often hateful form of nationalism. The rise of jingoistic nationalism elsewhere encourages the rise of Hindutva to match or rival them.

A fourth reason for the ascendancy of jingoism is the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in our own backyard. The state and society of Pakistan are becoming more and more fundamentalist. Once they persecuted Hindus and Christians; now they persecute Ahmadiyyas and Shias too. And Bangladesh is also witnessing a rising tide of violence against religious minorities. Since religious fundamentalisms are rivalrous and competitive, every act of violence against a Hindu in Bangaldesh motivates and emboldens those who want to persecute Muslims in India.

The BJP and the RSS claim to be authentically Indian, and damn the rest of us as foreigners. Intellectuals such as myself are dismissed as Macaulayputras, or, if we are female, as Macaulayputris, as bastard children of Macaulay, Marx and Mill. As a historian, I would say that the Hindutvawadis are the true foreigners. Their model of nationalism—one religion, one language, one enemy—is totally inspired by nineteenth century Europe, unlike the Gandhian model of nationalism which was an innovative swadeshi response to Indian conditions, designed to take account of cultural diversity and to tackle caste and gender inequality.

If the Sanghi model of nationalism is inspired by Europe, their model of statecraft is Middle Eastern in origin. In medieval times, from about the eleventh to the sixteenth century, there were states where monarchs were Muslims and the majority of the population was Muslim, but a substantial minority was non-Muslim, composed in the main of Jews and Christians. In these medieval Islamic states, there were three categories of citizens. The first-class citizens were Muslims, who prayed five times a day and went to mosque every Friday, and who believed that the Quran was the word of God. The second-class citizens were Jews and Christians whose prophets were admired by Muslims, as preceding Mohammed, the last and the greatest prophet. Third-class citizens were those who were neither Jews nor Christians nor Muslims. These were the unbelievers, the Kafirs.

In medieval Muslim states, Jews and Christians, the ‘People of the Book’, were given the term ‘Dhimmi’, which in Arabic means ‘protected person’. As a protected person, they had certain rights. They could go to the synagogue or church; they could own a shop; they could raise a family. But other rights were denied them. They could not enrol in the military, serve in the government, be a minister or prime minister. Nor, unlike Muslims, could they convert other citizens to their faith.

The Hindutva model is being applied in Yogi Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh

Such was the second-class status of Jews and Christians in medieval Islam. This model was applied in Medina and Andalucia, and in Ottoman Turkey. While Kafirs (including Hindus) had to be suppressed and subdued, Jews and Christians could practise their profession and raise their family, and live peacable lives so long as they did not ask for the same rights as Muslims.

This is precisely how Hindutvawadis want to run politics in our country today. Muslims and Christians in India now must be like Jews and Christians of the medieval Middle East. This model is being applied most energetically in India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh. As the slogans go: UP mein rehna hai to Yogi Yogi kehna padega. UP mein rehna hai to Ram Mandir banana padega. UP mein rehna hai to gau puja karna padega. If Muslims in UP accept the theological, political and social superiority of Hindus they shall not be persecuted or killed. But if they demand equal rights they might be.

So this is the new model of nationalism on offer in India today: equal parts nineteenth century Europe; equal parts fifteenth century Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Egypt. What is indigenous about it? What is decent, moral, wise or democratic about it?

The new jingoism in our country is a curious mixture of outdated ideas of nationalism mixed with profoundly anti-democratic ideas of citizenship. And yet it finds wide acceptance. This is because the anti-patriotism of the Indian Left, the cronyism of the Congress party and the global rise of nativism and fundamentalism have acted as a spur, an encouragement, a provocation to the rise of jingoism in India. That does not mean that we should accept it as legitimate, or even as Indian. Those of us who are constitutional patriots must continue to stand up for the values on which our nation was nurtured, built and sustained. For, if the Hindutvawadis are to continue unchecked and unchallenged, they will destroy India, culturally as well as economically.

The political and ideological battle in India today is between patriotism and jingoism. The battle is currently asymmetrical, because the jingoists are in power, and because they have a party articulating and imposing their views. The constitutional patriotism of Gandhi, Tagore and Ambedkar has no such party active today. The Communists followed Lenin and Stalin rather than Gandhi and Tagore; and the Congress has turned its back on its own founders. But while we patriots may not have a party or political vehicle, we should carry on the good fight for our values even in its absence. For citizenship is an everyday affair. It is not just about casting your vote once every five years. It is about affirming the values of pluralism, democracy, decency and non-violence every single day of our lives. So long as enough of us do so with vigour and honesty, the jingoists will not win, and the Republic will survive.

***

The killing fields of the Great War were manned by recruits who answered the call to patriotic duty. But years of meaningless slaughter opened their eyes to the emptiness of that appeal. The British war poets gave eloquent voice to this disgust. In his devastatingly graphic Dulce Et Decorum Est, Wilfred Owen uncovers the bare fangs of that high Latin ideal: “My friend, you would not tell with such high zest/To children ardent for some desperate glory/The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/Pro patria mori.”

(This essay is based on a lecture given in memory of Justice Sunanda Bhandare, one of our bravest and most far-sighted jurists, and a true patriot.)

Ramachandra Guha is a historian. He is the author of, among other books, India After Gandhi.

Tags