On October 17, 1949, as the Preamble of the Constitution of an independent India was brought on the table for discussion in the Constituent Assembly, the debate over secularism took a determinist shape that still impacts its understanding.

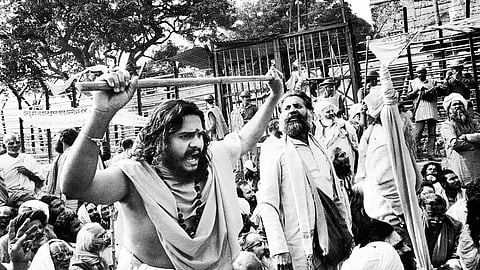

Power Politics: A Test Of Indian Secularism

Indian secularism has had a chequered history where political expediency means trading off secular ideals for power

H.V. Kamath started the discussion by moving an amendment that proposed to start the Preamble with ‘In the name of God’. Following Kamath, Shibban Lal Saksena and Pandit Govind Malviya also moved similar amendments and said that it was under no circumstances ‘anti-secular’ and of ‘narrow, sectarian spirit’ as termed by Pandit H.N. Kunzru. Rather, citing the use of the word ‘God’ in the Preamble of the Irish Constitution, Malviya said that by invoking phrases like “By the grace of the Supreme Being, lord of the universe, called by different names by different peoples of the world”, they were not sanctifying God of any particular religion and hence must not be considered contrary to the spirit of secularism.

Adding to this argument, Kamath said that religion was the “voice of our ancient civilisation” and the invocation of Gods only reflects the will and spirit of the Indian people. Rajendra Prasad, as the president of the Constituent Assembly, though tried to dissuade Kamath by referring to the provisions of the Constitution which mandated ministers to take oath either in their God’s name or by ‘solemnly affirm(ing)’, Kamath was adamant.

Purnima Banerji, a firebrand nationalist and one of the most vibrant women members of the assembly, opposed him and said that the sacred God cannot be put to the test of democratic voting. She asked Kamath “not to put us to the embarrassment of having to vote upon God”.

The amendment was defeated by 68 to 41. However, what remained unresolved was the inclusion of the word ‘secularism’ in the Preamble. When Brajeshwar Prasad, an avowed secularist from Bihar, called for the inclusion of the contentious word ‘secular’ in the Preamble, he became the subject of ridicule.

Shefali Jha in her 2006 paper titled ‘Secularism in the Constituent Assembly Debates, 1946–1950’, published in the Economic & Political Weekly (EPW), said that the members not only refused to include the word but also “ridiculed Brajeshwar Prasad’s attempt at making the Constitution a socialist instead of a liberal democratic document”.

ALSO READ: What Does Secularism Mean Around The World?

However, ‘secularism’ during the Constituent Assembly debates mostly treaded through two paths—the non-engagement policy following the European version of secularism and the equal distant policy that political scientist Rajeev Bhargava later termed as ‘principled distance’ policy. The notion of European secularism was upheld by leaders like Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, G.B. Pant and Tajamul Hussain. They argued that nationalism should be the modern basis of unity instead of religion and called for an individual-based citizenship abandoning earlier community-based identity.

Their call for relegating religion to the private sphere, however, was not supported by leaders like K.M. Munshi, J.B. Kripalani and Lakshmikant Mitra. Munshi said, “We are a people with deeply religious moorings. At the same time, we have a living tradition of religious tolerance—the result of the broad outlook of Hinduism that all religions lead to the same god… In view of this situation, our state could not possibly have a state religion nor could a rigid line be drawn between the state and the church as in the US.”

The ambiguity borne out of these contentions that neither separation of state and religion nor a declaration of state religion would work for India led to an India-specific policy of secularism, where the state would maintain equal distance from all religions. However, as the country celebrates 75 years of Independence, the question remains how fair has been the performance of Indian secularism? What were the hurdles it had to overcome? A journey through the past decades takes us to the moments when secularism needed to redefine, if not reimagine, its ideals.

According to Professor Mujibur Rehman, author of Communalism in Postcolonial India, secularism in India was a product of the Hindu–Muslim debate. The notion after Partition was about giving “more than what Pakistan can offer”. Speaking to Outlook, he says, “We were never a secular country, but we always had an ambition to build a secular state and a secular society.” The formation of Pakistan on religious lines is what made the Indian National Congress choose the path of secularism that the proponents of Hindu Rashtra inevitably opposed, adds Rehman.

Political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot notes in The BJP in Power: Indian Democracy and Religious Nationalism that Indian secularism more or less performed well between the 1950s and the 1970s. Barring the Jabalpur riots in 1961, caused mostly due to the economic competition between Hindu and Muslim bidi manufacturers, hardly any significant communal disturbance happened in this period. Asghar Ali Engineer attributes the absence of any unproportionate violence during the period to the post-Partition loss of dominance of Muslims in northern India. In his paper ‘Communal Conflict after 1950: A Perspective’, published way back in 1992 in the EPW, Engineer, however, pointed out how the Jabalpur riots played a role in the formation of the Majlis-e-Mushwarat, the first organisation of Muslims in Independent India that opposed Nehruvian secularism and encouraged community-based mobilisation. The consecutive riots of Ranchi in 1967 and Jamshedpur in 1969, along with several other minor outbreaks, coupled with the fervour of Indian nationalism in the post-1965 India–Pakistan war mostly defined this period.

But the next decade was not that much cordial to the idea of Indian secularism. After assuming power, Indira Gandhi had to go through tests of the time. Whereas her policy of nationalising banks along with the ‘Gharibi hatao’ (remove poverty) campaign, to some extent, won back the Muslim and Dalit votes, the Hindu right wing, within and outside the Congress, was not happy. The formation of All India Muslim Law Board in 1972 and recognition of Aligarh Muslim University as a minority institution further added salt to the injury.

As Rehman points out, Indira Gandhi passed through different ideological phases in her political career depending on the political expediency. In once such phase, she began pandering to the Hindu right. Her declaration of Emergency along with the forced family planning measures did not go down well with Muslims, which reflected in the transfer of their votes to the Janata Party. At this juncture, she was found inaugurating Bharat Mata Mandir in 1983 to woo the Vishwa Hindu Parishad.

Her decision to promote secessionist Sikhs like Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale to finish the Opposition Shiromani Akali Dal in Punjab, as Jaffrelot notes, cost her life. Operation Blue Star at the Golden Temple, the holiest of Sikh shrines, hurt the sentiments of the otherwise peaceful community and led to her assassination by her Sikh bodyguards on October 31, 1984, barely four months after the army action in June. The anti-Sikh riots, which led to the killing of thousands of Sikhs, with alleged complicity of the leaders of her party, brought Indian secularism into question.

Rajiv Gandhi, her successor son, also failed the test of secularism miserably. When Shah Bano, a Muslim woman, won her right to alimony after divorce under Section 125 of CrPC in the Supreme Court, Muslim hardliners in thousands hit the streets, saying that it was an infringement of the Muslim Personal Law and questioned the judiciary’s authority to interpret the Holy Quran. Under pressure from the Muslim clergy and fearing the loss of votes, the Rajiv Gandhi government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, exempting Muslims from Section 125 of CrPC. This gave fresh impetus to the Hindu right-wing forces to mobilise against what they called Muslim appeasement. This was the time when the discourse of the Hindu right evolved around “positive secularism and negative secularism”, says Rehman. “The basic understanding of the Hindu right was that secularism was not a bad thing, but whatever these so-called secularist parties have been doing, whether it was the Congress, the National Front or the Janta Dal, they are all trying to appease and were doing all kind of vote bank politics,” he adds.

The annulment of Shah Bano judgment opened the floodgates of competitive communalism that resulted in Rajiv Gandhi’s controversial decision to open the Babri Masjid for Hindus to worship Lord Rama. Closed for more than four decades after the idol was placed inside the mosque in 1948, the Babri Masjid became the rallying point for the mobilisation of Hindus.

With the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, two years after L.K. Advani’s controversial Ratha Yatra, and the consecutive riots in several parts of the country, Indian secularism lost its fundamental essence. From the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance coming to power in 1998 through the UPA-I and UPA-II, according to Rehman, the discourse of secularism though didn’t fully lose steam, with the emergence of Narendra Modi, it got subsided. Says Rehman, “One good thing about Prime Minister Narendra Modi is that unlike the other Hindu leaders, who indulge in doublespeak—talk about secularism but practise Hindutva and majoritarian politics—he has been very upfront.”

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, the abrogation of Article 370 and the proposed promulgation of a Uniform Civil Code are all part of the Hindu right-wing agenda. So, to understand and revisit the fate of Indian secularism at such a juncture, one can do nothing but recall the words of Jawaharlal Nehru in 1961. Attributing the meaning of secularism to equal and dignified lives, the first prime minister of India reimagined it in these words: “We talk about a secular state in India. It is perhaps not very easy even to find a good word in Hindi for ‘secular.’ Some people think it means something opposed to religion. That obviously is not correct. What it means is that it is a state which honours all faiths equally and gives them equal opportunities.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "Power Politics")

Tags