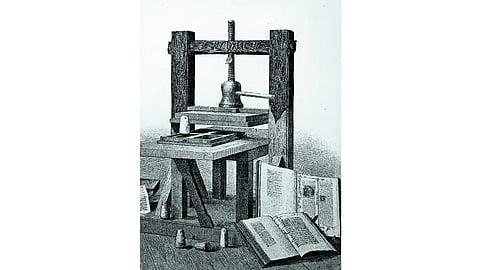

As a schoolboy growing up in Goa of the 1970s, there was always a shortage of children’s storybooks one could buy. Two decades later, while on a scholarship, a visit to the Gutenberg Museum opposite the cathedral in the old part of Mainz in Germany—the European home of printing—I learnt an unexpected fact. Goa had indeed been the place where the first Gutenberg-style printing press in entire Asia got going, way back in 1556. How did these two seemingly contradictory realities match? It took a long journey to find out the answer. Part of the journey involved creating a small, indie publishing venture, not coincidentally called Goa 1556 [goa1556.in]. It’s small and artisanal, but in the last 15 years, has launched some 150 titles out of Goa.

Printing From The Margin Of Margins: Can Goa Retrieve Its Rich History In Publishing?

Why books minus touristy cliches, voices from outside the metros, and inexpensive printing options in small states like Goa are the needs of the hour

Somewhere in between, it became increasingly clear that small places—not just Goa—don’t make much commercial sense to attract the attention of mainstream book publishers. Major book publishing houses would, at best, do a book on the region once in every two or three years. These would be authored by ‘big’ names (read: easily recognisable) or ideated on the stereotypical lens through which Goa is seen: tourism, sossegado, Portuguese colonialism, or mining.

ALSO READ: Tears Of The Mermaid: The Melancholy Of Goa

Then, life has its own logic. One graduated from being a buyer of Goa books, to a collector, a reviewer of such titles and finally a (modest) publisher. It became clear that authors were having a tough time to get their work published. If published, finding a market was a struggle. Distribution was broken and the readership, limited. Even locally published books found it hard to break even. Yet, generating locally relevant knowledge was critical. This is not Goa’s plight alone. Many parts of the country outside the metros are publishing deserts. Larger states with more speakers of a language have an advantage; they can make publishing viable. But, even in a big state, the focus tends to be on bigger cities. So, how does one give a voice to a country of potentially 1.3 billion stories?

Kerala might be an exception with its reading campaigns, co-operative publishing ventures, and library movement, going back decades. Maharashtra might have a fairly connected library network. But even here, things are not smooth. A biggish player from the world of Marathi publishing confided that demonetisation, GST (18 per cent on printing, including books) and the pandemic had broken their back too. Due to this, regular bill-payers had slowed down, and many others turned defaulters.

***

It was a bold and foolhardy venture. To create books with no capital or loans meant trying every trick in the book (pun intended) to make the tomes viable. Co-publishing with local bookshops was one option. Accessing the few—now vanishing—small grants where available, was another. So was co-branding with other institutions. Offering consultancies and editing support sometimes helped bridge the financial gap. In a handful of notable cases, crowdsourcing and even crowdfunding helped. Currently, a Konkani-English dictionary is being worked on. It is in the neglected Roman script, de-legitimised under the Goa Official Language Act of 1987. Crowdfunding has covered the printing costs for 500 copies of the 400+page book, even before going to press.

The field is a slow and poor paymaster. Yet, there is crucial work to be done. Local books help a society shape its own priorities. This is a need of India that the global South needs to address. Way back in the 1970s, there was much concern over the need to create regional knowledge and publish books locally. Those issues seem largely forgotten now. Demand creates its own supply. Options to publish throw up scores of ideas, including in more ‘crucial’ fields like non-fiction. Our modest operations created works like a readable two-volume study of Goa’s anthropology (Robert S Newman), an anthology of Goan writing (edited by Peter Nazareth, republished), the charming Espi Mai stories set in Goa (Anita Pinto), among others. The last, Pinto’s stories for children, got translated from English into Konkani (both the Roman and Devanagari scripts), Marathi and even Portuguese. The last was crowd-supported by diverse volunteers. This is unusual for a children’s story book, especially one coming from a tiny region of India.

But some trends are worrying. Indian book publishing was gung-ho about its potential in the first decade of this century. Of late, it seems to be floundering, and its promises less visible. We seem to have lost our vision of promoting skills and inexpensive printing options to make the word available to many. Likewise, the role of the National Book Trust in promoting book publishing skills has sadly diminished. Bookshops in many parts of the country have closed (including the iconic Other India Bookstore, and the charming 6 Assagao, both in Goa). Even securing an ISBN number for a book can be a struggle, as if this was being used as a tool for censorship.

India needs its diversity of ideas, especially true of places ‘on the periphery’ (as Goa became over the centuries). It would be easier to bring out books here on touristic clichés, but the real need is for something else. It is why Goa 1556’s focus stays on non-fiction, local titles, informative and readable books that tell the “Goa story”. (These are mostly in English, but a few in Konkani, Marathi, Portuguese and one in Spanish.)

Readers appreciate the titles on offer and attempts to price books affordably. Authors sometimes expect the low barriers of indie publishing with the financial impact of the mainstream publishing. Lit fests still value books published in big centres more than locally produced ones.

But together with publishing, other aspects of the book ecosystem also need to be nurtured. Goa currently falls short in libraries, campaigns to spread reading, and discussions about books. Centuries back, this tiny place played a crucial role in collating and sharing—globally—information about Asian languages, geography, local plants and medicines, and other such impactful information that shaped the East-West encounter. Books can offer low and slow returns. They can also open new perspectives on smaller regions. More regional book publishing would only make the subcontinent richer in its understanding and expression.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Printing From the Margin of Margins")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Frederick Noronha is goa-based writer and founder of publishing house, Goa 1556

Tags