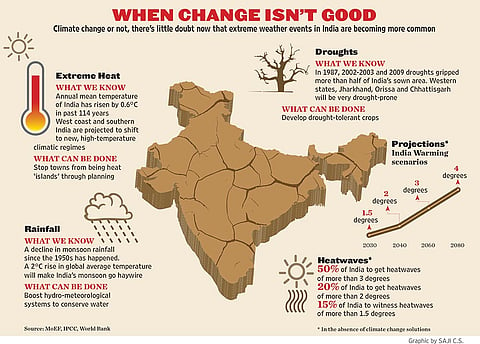

Indian scientists who engage in climate research and are grappling with possible solutions say the footprints of changing climate conditions in the country are now visible—not just in copious amounts of data, but to the naked eye. This was pointed out to Prime Minister Narendra Modi over two years ago, when he first chaired the recast PM’s Council on Climate Change. The evidence lies strewn across the length and breadth of India. While droughts and unseasonal rains are seen as the more familiar markers, the deeper trails have led to remote corners upcountry, in the high seas and even on factory floors.

Rumble Of A Scary Trundle

The ominous footprints are no longer distant. We see them in Jharkhand’s paddy slopes, Andaman’s coral reefs, Bangalore’s garment units, Punjab’s wheat fields...

Here’s a snapshot of the not-so-hidden footprints of a changing climate. The Indian Ocean, without which the country cannot get its summer monsoon, is “significantly” warmer now than 50 years earlier. Maltos, an indigenous community in the forests of Jharkhand, one of India’s poorest states, are now left battling strange intruders into their bucolic life: swarms of unknown pests. Cities have been brought to a halt by catastrophic rains. Apple orchards of Himachal Pradesh are shifting higher up in search of cooler temperatures. Rainfall in the Western Ghats is declining, compared to India’s eastern coast.

In the climate meeting Modi chaired in January 2015, the PM had said, according to a person who attended it, India’s traditions of prakriti prem (love of nature) means it had a unique advantage in dealing with climate. India, which is one of the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters, has ratified the Paris global climate agreement. This means the country will have to ensure that 40 per cent of India’s electricity will, by 2030, come from non-fossil renewable sources.

However, it will take more for India to walk the climate talk, for any positive impact of mitigation measures can take years to implement, scientists say.

“It’s been good so far,” says farmer Satyapal Singh. The wheat crop on his five-acre farm near Haryana’s Kurukshetra University is gradually turning brown now—from an iridescent green a month ago. This means the grains are ripening. Rising temperatures over the Indo-Gangetic plains, however, worry Singh. The mercury has quickened to 37 degree Celsius, an alarming four-degree clip in just over a week. Singh’s farm is one among several across states that scientists are continuously tracking as part of a high-tech climate study.

Wheat is now clearly India’s most vulnerable crop when it comes to climate effects. In 2010, a sudden spike in temperature had cut wheat yields by 26 per cent in Punjab, according to the Borlaug Institute for South Asia, which works closely with the agriculture ministry. The national wheat output wasn’t affected much because the loss in yields was made up for by a larger crop area. Farmers didn’t anticipate the loss as the weather had been glitch-free right up until harvest time, recalls Singh.

Farmers like Singh may have been caught unawares, but scientists had already predicted such a possibility. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research had concluded—six years earlier—that grain yields could fall between 3 per cent and 4 per cent with every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature during grain filling—a stage that is like the adolescent years—of the wheat crop. Indian scientists have identified this increasingly common weather pattern—of sudden heat spells between March and April—as evidence of a changing climate.

Nearly two-thirds people of India’s 122-crore population rely on livelihoods that are climate-dependent. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that climate changes will be felt more acutely by the poor simply because they are less likely to have the financial resources to adapt.

Between 1973-1990 and 2000-2007, average winter temperatures have gone up by 3 degrees Celsius. Apples to become apples need what is called a minimum chill factor—this is the number of hours when the temperature should be below about 7 degrees Celsius, but above freezing. This warming has caused apple belts to move higher in Lahaul-Spiti.

Recently, the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services concluded that coral bleaching—a disease that discolours and eventually destroys precious coral reef ecosystems—has reached the Andamans from the Pacific.

In 2000, the maximum temperature during January-February was 24.82 degree Celsius. This increased to 24.9 degree Celsius in 2014, recording a growth of 0.08 degree Celsius in 14 years. The ICAR has identified that of the 280 lakh hectares area under wheat in India, about 90 lakh hectares have become vulnerable to such sudden heat stress.

By 2020, climate change is projected to reduce potato yields in states across the Indo-Gangetic plains by 2.5 per cent in certain pockets, unless adaptation measures are taken. These are the findings of a study led by one of India’s top climate scientist Pramod Aggarwal, a former national professor at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI).

Aggarwal should know. He was the coordinating lead author for the chapter on food of the fourth assessment report of the IPCC and also its review editor of the landmark 5th assessment report. “You must have heard people ordinarily say ‘aajkal garmi badh gayi hai’ (the weather has got a lot warmer these days). They are right. People are able to relate to these changes you see,” he says.

Springtime hailstorms, in states such as Maharashtra, for example, are being acutely felt relatively recently. Aggarwal says hailstorms during spring are typical of the changes. He weighs in on the debate on the scepticism around climate change. “Even if you remove the words ‘climate change’, materially, there is no change in the impacts from events such as unseasonal rains, increase in intensity of floods, droughts followed by floods and vice versa. There is now sufficient information on these real changes.”

Hailstorms have caused severe losses to wheat farmers in the past few years, like in this year. In 2014, unseasonal rains and sudden hailstorms pounded 11 million hectares, devastating crops in 14 states, including Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Punjab. Extreme weather events tend to increase financial costs of the government and poor farmers alike. In 2015, the Centre had to pay out Rs 8,000 crore as compensation for unseasonal rains alone, roughly the same amount the country spends on children’s mid-day meal programme.

Maharashtra has witnessed pre-monsoon hailstorms for four years in a row now. Scientists say these events signal the actual metrics of climate impacts in India: the mean change in temperature and rainfall. The most visible impacts of global warming in India will be in agriculture, but they won’t be restricted to the farm sector alone.

Achyuta Adhvaryu, who teaches at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, had been alarmed by findings by Anant Sudarshan, the India director of the Energy Policy Institute at Chicago University, that global temperature increases may have reduced Indian manufacturing output by 3 per cent relative to a zero-warming scenario. So, Adhvaryu and a colleague decided to look for the evidence down at the level of an individual garment factory in Bangalore.

Their study is one of the latest to gauge how heat and climate conditions are impacting manufacturing in India. “We find impacts of both heat and air pollution levels (PM 2.5) on the productivity of garment workers. On hot days, raising the average temperature by 1 degree Celsius decreases productivity by about 4 per cent,” Adhvaryu tells Outlook. Similarly, a “one-standard deviation spike” in air pollution, he says, caused a 1.5 per cent dip in productivity.

The evidence of extreme weather has only got starker in the past three years. Last year, the planet recorded its hottest year ever. It broke a record set only a year ago, which in turn smashed the previous year’s record in 2014. In other words, each of the past three years was the warmest in Earth’s recorded history.

The southwest monsoon, which accounts for nearly 80 per cent of the country’s rainfall, is playing truant in about four out of every 10 years. This makes forecasting tougher for the India Meteorological Department. Years 2014 and 2015 were the only fourth instance of two back-to-back monsoon failure years in 115 years, according to the Met department. “Our studies show the Indian Ocean has significantly warmed in 50 years—by about 0.6 degree Celsius,” says R. Krishnan, a climatologist from the premier Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology. “Monsoon has been declining in the Western Ghats and interior areas such as Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh by about 6-7 per cent.”

Less noticed are the impacts on smaller communities. In Jharkhand, researchers have found that the Maltos, a traditional community, is already bearing the brunt. Their highland forest habitats and paddy slopes in Sahibganj district have seen a clear decline in rainfall, according to a study by researcher Hoinu Kipgen Lamtinhoi. The state government’s Action Plan for Climate Change notes the densely forested district frequently goes dry now. This has forced Maltos to migrate downhill towards the traditional habitats of Santhals, a rival community, exposing them to social conflict.

Scientists like Aggarwal believe the debate between climate-change asserters and deniers isn’t important. What is important is to act. “There is sufficient information on extreme weather events. We need early warning systems, scientific capacity to mitigate impacts, infrastructure and operational readiness,” he says. For instance, technologies to mop up excess water during flash floods and use them during snap droughts. Solutions are trickling in, such as drought-tolerant wheat varieties of the IARI. The science and technology ministry is holding a workshop on heatwaves this week. These however are just a speck in what must be a gargantuan effort, he says.