Probe Panel Notes

Sheep Call The Shepherd Wolf

A 2016 land deal by Kerala’s Catholic Church ensnares the top clergy in a legal case. As stories on intrigues grow, the laity is furious.

- It is in violation of the Church laws that full rights are given to the Finance Officer, who seems to have taken liberties to sell the archdiocese’s land

- It seems that the Finance Officer was concealing facts from the Finance Council and pretending that sale of properties are yet to take place

- Saju Varghese (the real estate agent) grabbed the prime land of 62 cents without paying the sale consideration

- The Consulters’ Forum didn’t discuss the case of 23 acres of land bought at Mattoor. This has violated common law, the archdiocese’s statutes.

- Buying land in such a remote place points to the engagement of real estate lobby. Such dead investments, when the archdiocese is in debt.

- The total liability in 2015 was Rs 15.83 crore. But in three years, the total loan liability escalated to Rs 86.33 cr as on Nov 30, 2017, with an increase in liability of Rs 70.54 cr.

***

It is a trial of biblical proportions. For the first time ever, a police case has been filed against top functionaries of the Catholic Church in India. The controversy is over a land fraud of the Church—and it came to a head when a first information report was registered against the chief hierarch of the religious denomination’s Kerala chapter. Cardinal Mar George Alencherry is not just the Major Archbishop of the Syro Malabar Catholic Church, he controls the archdiocese of Ernakulam-Angamaly under which the alleged crime happened in the past two years.

On March 6, the state’s high court ordered that an FIR be filed against the septuagenarian patriarch for “irregularities” in the deal over a purchase of land 35 km north of Kochi. The single-judge bench also directed the police to name Joshy Puthuva and Sebastian Vadakkumpadan, both priests, besides real-estate agent Saju Varghese. Within a week, on March 12, the police finally filed criminal charges against all the accused.

The case has split the members of the archdiocese right down the middle. Many priests from within the Church are openly speaking out against Alencherry, 72. The laity, said to total around 46 lakh, is also up in arms—and is demanding a greater say in the Church’s day-to-day affairs. As all sorts of allegations and conspiracy theories fly around in full public glare, some say it has the makings of a long-drawn coup against the Cardinal.

The laity takes out a march against the ‘scam’, in Pala, Kottayam, on January 27

At the heart of the controversy are dubious land deals worth nearly Rs 80 crore and unaccounted funds to the tune of Rs 14 crore. Earlier, on February 16, the petitioners attempted to get the police to file a complaint against the Cardinal. The police refused to oblige, and two writs were submitted in the high court the same day. The drama escalated when Alencherry’s counsel reiterated in the court that the Pope is the only authority to whom the Cardinal is answerable. The Cardinal, the argument went, is free to “do anything with regard to the properties of the diocese”. That prompted Justice B. Kemal Pasha to ask the counsel whether the Cardinal could be considered a king. The response was an “emphatic yes”. The judge, in his verdict, called the land deal “shady”, and said Alencherry “cannot recklessly deal with the property and simply say the diocese has lost money”.

As the case proceeded, special public prosecutor Suman Chakravarthy contended that the police had not taken up the dispute, as it was a civil case. Now, after the court order, the Cardinal and the three others stare at charges of breach of trust, conspiracy and cheating. Some senior priests of the Church have also accused the Cardinal of hiding the truth about a liability of close to Rs 80 crore. For instance, Fr Paul Thelakkat, former spokesperson of the archdiocese, tells Outlook that the “land scam has literally saddened and disturbed if not angered the faithful and the clergy of the Church”.

On the other hand, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) is defending Alencherry. “I am with him,” says CBCI president Oswald Gracias in Delhi. This was just hours after he met Prime Minister Narendra Modi on March 20 to discuss the possibility of an India visit by Pope Francis, the supreme pontiff of the worldwide Catholic Church. He chose not to comment any further on the matter.

Down the country, the “land scam” Fr Thelakkat refers to happened as a result of a proposed medical college that was supposed to come up at Mattoor near Angamaly in central Kerala. To facilitate this, five plots of close to three acres of Church land were sold, allegedly below market price, for a pittance: Rs 27 crore. To top that, the Church estimates that only about Rs 13 crore of it has been received so far. The purported scam has become a public spectacle what with 200 priests marching to Alencherry’s official residence on March 9, asking him to step down until the criminal charges are cleared. A couple of days later, the laity took out a much bigger rally, shouting slogans against the Cardinal.

Alencherry is one of five people to hold such a post in the country with the cardinalate among the uppermost in the Roman Catholic hierarchy forming the group that elects the Pope. It was in February 2012 that Pope Benedict XVI elevated Alencherry as a Cardinal, less than a year after he was the first Major Archbishop to be elected by the synod as the head of the Syro Malabar Church. It lays claim to being the largest Eastern Catholic Church apart from the Ukrainian Church that has followers roughly equalling the Syro Malabar in numbers.

The All Kerala Church Act Action Council meets on February 24

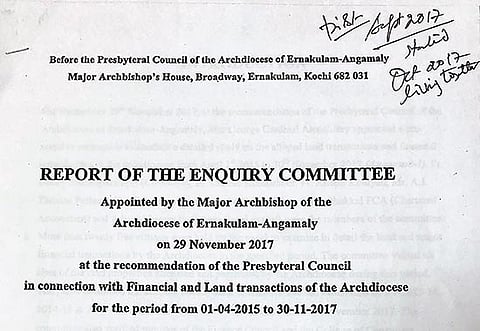

Last year, Alencherry appointed a committee to look into the Church’s land deals between April 1, 2015, and November 30, 2017. Its report was submitted on January 4. The same day, the Church’s five-member Presbyters’ Council with Alencherry at the helm was slated to discuss the report and outline a complaint to the Pope. They couldn’t meet as the Cardinal reportedly told the body that he had been “physically prevented by a group of laymen”. Outlook has a copy of the enquiry committee report that says that the Church’s total loan liability in the period had “escalated” to about Rs 86 crore, and estimated a loss on sale and purchase of land at close to Rs 46 crore.

“We have violated the canon laws and the civil laws of the land,” says Benny Maramparampil, the priest who headed the probe panel. “This is a violation; it should be rectified.” He says the plan for the medical college, which had been dropped, was revived in 2013 under Alencherry as the Cardinal. To him, the loan the Church took was “totally unproductive” with a high interest rate of close to Rs 70 lakh per month. To cut losses, the Church decided to dispose of about three acres of other property. The sale, by splitting the land in 36 plots, fetched close to Rs 27 crore. “Where did this money go,”asks Maramparampil. “The real estate agent says he had paid this amount but the Church’s finance officer (Fr Puthuva), and the archbishop says we still have Rs 18 crore to receive.” Outlook has learnt from people close to the developments that the current outstanding amount is Rs 14 crore.

Maramparampil also tells Outlook of another supposed land deal which didn’t go through. “Surprisingly, three weeks ago, we found another set of documents. There was a hidden plan to exchange prime plots at Thevara and near Ambedkar Stadium (both in Kochi) and a plot on the National Highway and they would in turn give us 70 acres of rubber plantation,” he says. “These documents were typed and printed on February 15, 2017. The stamp paper value is Rs 80 lakh and it was signed by the archbishop.”

Auxiliary Bishop Mar Sebastian Adayanthrath

Fr Antony Poothavelil of the pro-Cardinal group counters the version. He says the transaction happened during demonetisation (announced on November 8, 2016), as a result of which the mediator could not give the full amount. “Before receiving the amount, the Cardinal had signed the documents as per the finance officer’s advice. Only later he came to know that the full amount had not been accounted. Yet Alencherry took the responsibility,” adds Poothavelil, suggesting that the deal earned the Cardinal and the officer no financial advantage. “It’s an internal problem of the archdiocese. No external forum must interfere in it. The priests shouldn’t have raised this in the media. They cannot solve the matter; they want to remove the Cardinal,” he says.

Sebastian Paul, a former MP from Ernakulam, agrees. “In effect, the Cardinal has become captive. He stands as an accused,” notes the CPI(M) leader. “In a country of religious freedom, no Cardinal would have suffered such ignominy. It is a curious situation.”

Also, it is not just the clergy gunning for the Cardinal. The laity has also found their voice and is rekindling a demand: a new law that gives them greater powers in the affairs of the Church. The Kerala Catholic Church Reformation Movement says its primary issue is with treating the Church as private property. “The argument that it is private property is what the faithful is against. The land was given by the faithful; no one can question it,” says the movement’s founder George Moolechalil, editor of the monthly Sathyajwala. To him, the canon law tracing back to the Vatican’s notion that the Church’s property is that of the Pope (who delegates his subordinates to run it) is against the Indian Constitution.

Cardinal Gracias of the CBCI says matters of “greater transparency” and “good financial administration” were something he had discussed with bishops in Mumbai recently. “The canon laws have related measures—and are adequately supervised,” he says. “It’s not that we have something to hide. My fear is that those hostile could interfere.”

India does not have an administrative law in place for the Christian community as, for instance, the Wakf Board for the Muslims or Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee for the Sikhs. In 2009, a draft bill prepared by Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer sought to address this shortcoming, but the so-called ‘Church Act’ has not yet materialised. “First, they said they would take it seriously,” recalls Moolechalil. “Then the bishops opposed it. None of the governments listened.”

An Open Church Movement that fights “corruption” in the Catholic establishment even goes as far as to say that the Church works like a real estate company. “India is a sovereign state. The Church has challenged the country’s Constitution and the judiciary like a parallel government,” says the movement’s chairman, Reji Njallani. “The states do not know how much of the assets of the Christian churches are taxed. Foreign exchange fraud and tax evasion are brushed off under the pretext of philanthropy.”

The Catholic Layman’s Association concurs, and calls it a paradox. It is puzzled how the Church can get tax exemptions as a trust for a land it tells the court is private. M.L. George Maliyeckal, secretary of the association’s central executive committee, shows Outlook an affidavit by Mar Varkey Vithayathil, the earlier Archbishop, in a case from 1998 where the CLA was a petitioner and the Synod of Bishops of the Syro Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Church were the defendants. “As already stated, this defendant submits that the Syro Malabar Archiepiscopal Church is not an express of constructive trust created for public purposes of a Charitable or Religious Nature,” Vithayathil had written. Maliyeckal presents an order under the Income Tax Act from 2006 that in fact lists the Syro Malabar Church as a “public religious trust”.

Advocate A. Jayasankar, a media critic, says the Church owns the land, but that doesn’t mean the Major Archbishop can unilaterally buy or sell it. “There is an internal democratic system for acquiring and selling of property,” he adds.

The eruption of these debates in a legal space has also brought the focus back on infighting between power-jockeying factions within the Church. Insiders say the Church is divided into lobbies between the archdioceses of Ernakulam and Changanacherry (in Kottayam district), to which Cardinal Alencherry belongs. These are two groups, which Njallani says “are literally trying to destroy one another”. There are suggestions of a ‘coup’. The relations between Auxiliary Bishop Mar Sebastian Adayanthrath and Alencherry have “broken” of late. That, some in the know of things say, is the basis of the issue. “His (Adayanthrath’s) personal grievance against the Cardinal is the root of all problems,” says Poothavelil.

The combination of the tussle may be a bid to check the Cardinal from acquiring more power. A lawyer connected with the case believes Alencherry was not the frontrunner for the position he holds. Recent news reports quote unnamed priests within the Church hoping that the Syro Malabar denomination may get patriarchal status. That will confer the semi-autonomous church with more powers, allowing it to appoint its own bishops, without approval from Rome.

While the Cardinal looks for the clouds to clear, there is some reservation in the manner with which the high court has dealt with the case. Jayasankar and Maliyeckal feel that the two-judge bench that stayed an enquiry into the FIR should not have heard it in the first place.

The criminal proceedings in court aside, it appears that even the Pope cannot relieve the Archbishop of his duties, given the semi-autonomous nature of the Church. “To remove the Cardinal, the majority of bishops in the synod will have to write to Rome,” says Fr Poothavelil. “I don’t think many will do that.” It is all a messy interplay of hopes and aspirations.

By Siddhartha Mishra in Kochi