The sea of mourners at the recent funeral of a Lashkar-e-Toiba militant killed by security forces in Anantnag of south Kashmir reemphasised what we have already known, but refuse to readily acknowledge: an ever-deepening divide that separates the people of the otherwise picturesque region from the rest of the country, including the rulers in Delhi.

The Human On The K-Table: Time For A New Narrative To Break Logjam in Kashmir

It’s time for a new narrative and idiom to break the logjam. A Kashmir Roundtable finds early signs of meeting points that may open new roads.

The turnout at the funeral was also proof that with every ‘success’ registered by the security forces, we are not getting any closer to a resounding victory.

If anything, these ‘successes’ help in feeding local grievances and losing more ‘hearts and minds’. Lives are being lost without any tangible gains. Kashmiris are bearing the brunt of the turmoil, but even India is bleeding, with casualties on both sides, including soldiers made to make the ultimate sacrifice. This utter hopelessness and cycle of violence have been allowed to fester for far too long.

Indeed, few disputes in the world have defied a solution for this long. North and South Korea have been at daggers drawn for decades, but following a summit between Kim Jong-un of the reclusive Pyongyang regime and US President Donald Trump, a thaw looks imminent. In between, disputes such as the ones in Northern Ireland and Bosnia have been thrashed out. Kashmir, unfortunately, is one of the two long-running disagreements stubbornly refusing a solution. The other is Gaza, at the heart of what seems to be an intractable standoff between Palestinians and Israelis.

Stalemates are energy-sapping and self-defeating, so it would surely serve all of us well if an agreeable solution to Kashmir is arrived at the soonest. It is easier said than done, but what’s the harm in at least trying? If India is to prosper as a truly democratic nation, it cannot allow a sizeable section of its citizens—the Kashmiris—to live in perpetual disenchantment and despair. A breakthrough is the need of the hour.

But what is more urgently needed is a concerted and conscious bid to move away from oft-repeated phrases such as ‘Kashmiriyat’ and ‘healing touch’, and arrive at some concrete measures. The delusional clichés of the past have failed to deliver and we find ourselves trapped in a situation where positions have only hardened on either side. The last remnants of goodwill have seemingly dissipated and been replaced by hate in both public discourse and prime-time TV. There are many among us who see any word of sympathy for the Kashmiris as an act of treachery and betrayal. There is distrust and suspicion on the other side too, with many hot-heads amid their ranks.

It is, therefore, time for a new initiative, a new narrative and new idioms to break the logjam, infuse hope among a populace who feel they have none, and allow a well-meaning government to seize the initiative. Arriving at a common ground and a consensus is a minefield with divergent views and diverse actors involved: ranging from Muslim Kashmiris and Kashmiri Pandits, to non-state actors and our bete noire Pakistan.

Every roadmap must necessarily begin with brainstorming and Outlook for one made the effort to gather people in a quiet Delhi hotel for an honest discussion. The panelists were drawn from diverse sections—the RSS, the National Conference, the PDP, the Hurriyat, the army and also thinkers from Kashmir who have a lot at stake in the way things pan out in the Valley. The Kashmir Roundtable we hosted was necessarily rich and partly rhetorical. But amid the din and disagreements, there were also suggestions that bore the early signs of what could someday emerge as a meeting point.

Dialogue, we believe, is a must to solve a puzzle that many see mostly in terms of geopolitics and strategic affairs. For me though, it is a humanitarian tragedy that is at the core of the Kashmir issue, waiting for an urgent solution.

On June 28, eight people came together for an Outlook Roundtable on Kashmir in Delhi. RSS ideologue Seshadri Chari, former Northern Army Commander Lt Gen (retd) D.S. Hooda, three-time National Conference MLA Aga Ruhullah Mehdi, PDP leader Nayeema Mehjoor, advocate Abdul Majeed Banday, journalist Gowhar Geelani, scholar Basharat Ali and strategic expert Prof P. Stobdan participated in the discussion, which was moderated by TV anchor Barkha Dutt. The participants examined some of the fundamentals from their unique perspectives and sought to offer solutions. Excerpts:

Barkha: Hello and welcome to this Outlook Roundtable on Jammu and Kashmir. It’s difficult to draw a set of agreements on Kashmir, but almost everybody agrees on one thing: in 29 years of insurgency in the Valley, things have perhaps never been as critical as now. Old formulas have failed. We need a new language to talk about Kashmir, less artificial barriers, less artificial labels of Us and Them. But it’s become almost impossible to have an honest conversation: people are pushed to their ideological trenches. At this Roundtable, we attempt to change that. At the end of this conversation, we hope to reach a set of solutions—recommendations or suggestions we all agree on, coming from disparate backgrounds and points of view.

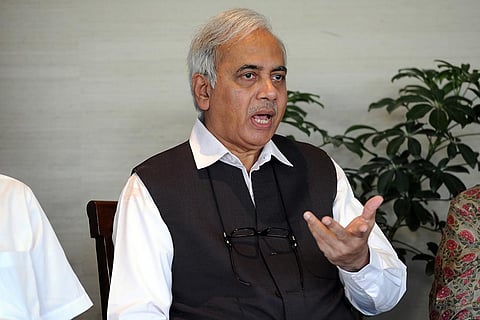

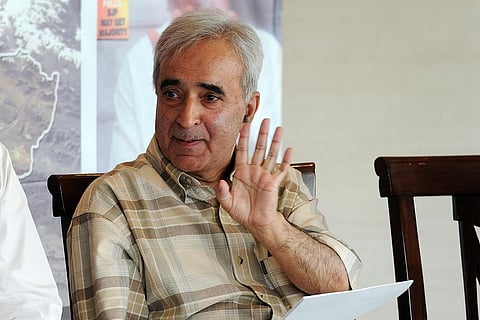

To my right is Seshadri Chari, writer and commentator. We have Gen Hooda, one of the wisest army officers I have known…he led the surgical strikes. Aga Mehdi is a young leader from a mainstream party—the National Conference. Journalist Gowhar Geelani, on my left, is an outspoken commentator. Abdul Majeed Banday, an advocate affiliated to the Kashmir Awareness group. And we have scholar Basharat Ali. The PDP’s Nayeema Mehjoor will join us. Novelist Siddhartha Gigoo had to drop out at the last minute. I’ll start by asking each speaker to talk about how the problem today is different from, say, a decade or two ago.

Lt Gen Hooda: Militancy was coming down, constantly, from 2001 to 2012-13. But popular anger, against whichever party was in power, wasted opportunities. That’s spilling out today on the streets. The youth coming out, stone-pelting, local (militant) recruitment…have increased. It’s morphed from a pure insurgency into something we will have to start thinking about.

Lt Gen Hooda: People say there’s radicalisation, but I’m not sure if it’s religious or political. You see much more anger in the young ones. I’m not sure if it’s got too much to do with religion, but, yes, there is radicalisation, there is anger.

Barkha: It’s an important distinction. Hardening of positions would mean radicalisation. But you are calling it political, not Islamist. Seshadri Chari, would you agree?

Chari: No, we can’t make it look so simple. There is nothing like (pure) political radicalisation. There’s anger everywhere...on the streets of Delhi, even in the tribal areas of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, also in Tuticorin. We cannot discuss today’s Kashmir without going into the past, the genesis of the problem, the details of those forces that want this issue to be kept alive. The most importance difference today is that the State responsible for the escalation of this problem, for the escalation of terror and radicalisation, has become more emboldened.

Read Also: Boots Off The Ground

Barkha: Which is Pakistan?

Chari: Yes, Pakistan.

Barkha: Aga Mehdi, as a young leader of a mainstream party in Kashmir, you are perhaps under pressure from both sides of the ideological divide. There are some things on which all national parties agree. But you also have to find a language that your own people can understand. What is the relevance today of mainstream Kashmiri parties that still swear allegiance to the Indian Constitution?

Aga: Their relevance is shrinking day by day. It would be fully misleading if anyone says the mainstream parties are as relevant as they were four years ago. New Delhi commits mistakes repeatedly and we have to pay for acts that are beyond us…. Omar Abdullah’s government recommended that we revoke AFSPA. The then home minister, P. Chidambaram, was ready to revoke AFSPA, but our friends in the security forces and the army….

Barkha: His proposal was shot down by the rest of the Congress-led government. I want to make this clear: it’s not only a Modi government policy.

Aga: The input of the security forces prevailed at the end of the day. It outweighed the wisdom of the home minister, who had the CM’s confidence. The CM suggested we at least start from Srinagar and Budgam, comparatively better districts in law and order and militancy. One mistake, and they took the credibility away from the CM.

Barkha: Gen Hooda, why is AFSPA such a symbol? When Omar was CM and more than 100 boys were killed, the protesters were actually clashing with the CRPF and the police, not the army. It’s intriguing: the army and AFSPA become symbols when actually most of the confrontation does not take place with the army.

Lt Gen Hooda: It’s become a symbol, something to talk about. If AFSPA is withdrawn, the army can’t operate. There’s no legal basis for the army. So the issue is not whether we remove AFSPA or not, but whether the army has done its role in J&K, and now it’s a purely law-and-order problem the police and the CRPF can deal with, so the army can withdraw? That’s a decision for the government....

Look at Jammu’s Reasi district, it’s militancy-free. But when we recommended that we pull the army out from there, the locals, particularly the Bakarwals, said, “No, we feel a sense of security.” The army provides a sense of security to some sections. Have we transited to a state where you can say, ‘Let’s pull out Rashtriya Rifles from Budgam, from South Kashmir, and let the police and the CRPF deal with it.’ I don’t think so.

Barkha: Gowhar, there’s a certain status quo response not just from all governments, but also from Kashmiri separatists. Have things changed?

Gowhar: When you started, you talked about the need to find a new vocabulary. Who is a ‘separatist’ in Kashmir? And who is ‘mainstream’? The mainstream leader here says the space for the mainstream is shrinking. So they are the separatists in the present circumstances, not the mainstream representing the dominant sentiment—77 per cent of the people wanted a solution outside the ambit of the Indian Constitution, according to a poll conducted for Outlook’s first ever issue (in 1995). If you did the same poll now, you would probably get 97 per cent.

Barkha: That would be within the Valley....

Gowhar: New Delhi follows a policy of Ds: Deny there is a problem. Defend your territory. Defeat and Destroy the enemies. This mindset needs to change. The policy should be 2As and 2Rs. Acknowledge there is a problem. Accept that the people want a political solution. Respect that, and Resolve. Do not live in denial. It’s the fourth generation of Kashmiris on the streets. Will people get pellets in their eyes just because somebody pays them Rs 500? Who are you kidding? We heard that demonetisation would end stone-pelting. So why is it happening now?

Third-party mediation is unacceptable. The four main parties in J&K—PDP, BJP, Congress and NC—should come together for an administrative council under the Governor. This is the first step towards a lasting solution. Anything is possible within the Indian Constitution.

Yes, India can have problems with Pakistan, and Pakistan can indeed fish in troubled waters. Pakistan supported the militancy in the early 1990s. But now you have SPOs, police personnel, decamping with their own rifles and joining Hizbul Mujahideen. You have young boys snatching rifles from the CRPF troopers and joining militant organisations. How can this be all about Pakistan and not the sentiment on the ground? We need to clear our heads about the ‘problem’ first. You say it’s just the Valley’s opinion. After the Outlook poll, there was the Chatham House survey, across both sides of the LoC—including Gilgit-Baltistan, Udhampur, Kathua...and Jammu is not only Jammu city and Kathua, but also Pir Panjal and Chenab valley. The survey found there’s an overwhelming majority in both parts that wants a solution outside the ambit of the Indian Constitution.

Barkha: Conversations were always Kashmir-centric and you never really include other places—that’s been one of the faultlines. But we do have to talk about them. Basharat, I often tell my Kashmiri friends, who abuse me with the same vitriol, that there’s a denial on their side too. Take Shujaat Bukhari’s assassination. He suffered what anybody who doesn’t take a clear side in Kashmir suffers. Shujaat tried to be moderate, and he was killed. The police say they have traced the killers…two local boys and one Pakistani. They say there’s a Lashkar link. Don’t Kashmiris too have to get over this denialism? Anyone who talks for dialogue is indeed killed, from Abdul Gani Lone to Shujaat.

Basharat: Barkha, I’d go back to where you started. You said it’s been 29 years since insurgency began. All conversations in Delhi about Kashmir begin from that point. As a sociologist, I want to take a step or two back and look at the larger picture. Nothing in society happens just like that. You don’t decide to pick up the gun on the spur of the moment. There’s a need to talk about the networks of social, political, religious and student organisations that existed before the insurgency. What were their conversations? What was their role? What were they asking? And what happened 29 years ago?

Well, just like elections, insurgency is a manifestation of a collective will…there’s a lot of academic work on this point. Voting or armed insurgency…both are a collective action at the end of the day.... You say we need a new language. That ‘Kashmiriyat’, ‘alienation’…all that is old. The BJP has already provided that new language. In the past four years, the phrase ‘collateral damage’ has gone missing from the Kashmir conversation. Why? Because the BJP has made the lines very clear. Every stone-pelter, everybody on the street, everybody who goes out to protect insurgents…is deemed a terrorist, and as killable as an insurgent. The distinction here has been made by the BJP, which I find rather interesting because they have allowed the Kashmiri collective to concretise the Us-vs-Them definition. Where people are willing to die and kill….

Barkha: So you are saying the hardline language has had the opposite effect.

Basharat: Exactly. The Congress had the same approach. But when people were killed during Congress regimes, it was always passed off as collateral damage. That was denial of the agency of those people— as Gowhar said, nobody comes out on the street just like that, without a certain decision-making happening before it.

Barkha: But what about the other denialism? Many Kashmiri friends privately say they think the Lashkar killed Shujaat, but if they say this openly, they will be killed too.

Gowhar: People have indeed been killed by both state and non-state actors. Take Jalil Andrabi’s case, which is parallel to Shujaat Bukhari’s case. If we talk about Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq, let’s also talk about Jalil Andrabi. Who killed Jalil Andrabi? Major Avtar Singh, who fled to California and shot himself dead too….

Basharat: What was Shujaat’s moderation about? He wanted a dialogue, right? That’s what the Hurriyat says too, except that they want India to recognise….

Barkha: Hurriyat’s Abdul Gani Lone was assassinated. He was shot in front of my own eyes. His son, who was then a separatist, and is today a mainstream leader, said on camera to Syed Ali Shah Geelani, “I will not let you enter my house because the killers of my father live in Pakistan.”

Read Also: The Cost Of Lost Opportunity In Kashmir

Chari: The Us-vs-Them wasn’t a creation of the BJP. Kashmir was one state, a Hindu state, a Muslim-dominated state ruled by a Hindu king. There was no Us-vs-Them then. When the Congress destabilised the Farooq Abdullah government, was it Us-vs-Them? The Congress was “us”? I’m not speaking here as a BJP person, I don’t represent the BJP at all, neither here nor outside. But let me say clearly…every party, Congress, BJP, PDP, NC and all others, they’ve had their prescriptions, their own contribution to the problem, and can offer solutions too. The question is, how do you deal with the idea of separatism that emanates from this kind of situation? In the early 1950s, there was a huge agitation in Tamil Nadu, the state I come from, against the imposition of Hindi. There was a demand for a separate Tamil country. But now it’s gone. In 1962, during the Chinese aggression, C.N. Annadurai publicly said this whole idea of a separate Tamil Nadu is all bogus. When I hear a Kashmiri talk about Kashmiriyat as something different, I ask, what about Tamiliyat, Marathiyat, Punjabiyat?

Barkha: This concretisation of Us-vs-Them...how did we come to this point where we make political or ideological differences so personal?

Chari: No, it’s not that we cannot converse. But if you tell me, ‘Look Mr Chari, you can come here, but these are the parameters within which you have to remain’, then I don’t think I should be coming here. Similarly, conversation takes place when there’s someone independent of the sides to preside over it.

Policies of suppression, bilateralism and selectivism have failed. The basic issue must be recognised in its historical context and a political process started involving all the involved parties. Only then can we try to reach a point agreeable to all.

Barkha: We may have the first of our proposed suggestions there! Any interlocutor, for lack of another word, should ideally not be one of the protagonists. I don’t mean they should not be Indian. I mean they should not be representing either the security agencies or the separatists. Is that your suggestion?

Chari: A third party will not be acceptable. If I ask you today, give me five names who you think would be fair to both sides....

Barkha: How did Atal Behari Vajpayee do it?

Chari: Someone like an Abdul Kalam, a Vajpayee...we are missing these people now.

Barkha: What’s the difference between the Kashmir policy of Vajpayee and Modi?

Read Also: The Pandit Across The Lidder

Chari: I don’t think there’s a great difference. The latter formed the BJP-PDP government. I was one of those not in favour of it, but in hindsight I think I was wrong and it should have continued. I think the officially given reasons are unacceptable. I am going on record to say this. In fact, I would have liked to see the four important parties in J&K—PDP, BJP, Congress and NC—come together for an administrative council under the Governor. That can be a first step. Everything is possible within the Constitution. That’s the difference when Vajpayee was asked about the Constitution.

Barkha: He said, “Insaniyat ke daayre mein jo mumkin ho” (Whatever is possible within the ambit of humanity).

Chari: The Constitution is the representative of that insaniyat ka daayra.

Barkha: Now, Mr Banday, it’s not that the Hurriyat has not had conversations with different governments before…with L.K. Advani, with Manmohan Singh. Even Hizbul Mujahideen militants have had conversations, at Nehru Guest House in Srinagar, no less. But today the fourth generation is questioning the Hurriyat. They ask why, for example, some of them still derive pensions from the State? Why do they take security? Mirwaiz Umer Farooq is protected by the J&K Police. And one of those police officers was lynched.

Banday: What has changed in the last 10 years is that alienation has increased. Somebody mentioned anger, but nobody talks about the basic issue. It has a historical background. It started in 1947. We must take the bull by the horns. The issue must be recognised in its context and a political process started involving all the involved parties. Only then can we try to reach a point agreeable to all. Three things have failed: bilateralism, the policy of suppression and selectivism.

Barkha: This is a difficult conversation because there’s little everyone agrees on. All protagonists are guilty of selectivism. But one suggestion has come from Chari: forget 2019, forget BJP, PDP, NC, Congress…have a united government.

Chari: Alienation is a misunderstood term. In the past 16 years, the Centre has given grants amounting to 54 per cent of the state’s revenue. If there’s no development in spite of this, let all the parties that ruled J&K hang their heads in shame and not talk about alienation.

Barkha: Is it a failure of governance?

Read Also: Kashmir Quagmire: The Legend Of ‘UNO Sahab’

Chari: Absolutely, the last opportunity that could probably be given is that (of a united government).

Barkha: Gen Hooda, you were there when Burhan Wani was killed and we saw the eruption of these faultlines. I remember you having to do what politicians should have been doing…a press conference where you said it’s time for us to sit together and have a conversation. If anyone is anti-national, it’s the politicians that have failed Kashmir. They send soldiers to die, to manage their problems. Soldiers carry the cross for failed politics in Kashmir.

Lt Gen Hooda: That’s true. It’s not a secret that the security situation has been brought under control a number of times, from where some kind of dialogue could have begun…. Chari’s is an excellent idea. Unfortunately, I think people have lost faith in the political parties. That’s why you see absolutely no outrage once the government has fallen. People are quite happy. It’s a good opportunity if Governor’s rule can bring some good governance.

Barkha: There was turmoil in the streets after Burhan was killed. And this happens to successive governments: every time there’s a crisis, there’s a paralysis of response. It’s almost as if politicians forget to talk to people. And the most reasonable voices come more from the army! Gen Hooda, when you sat at that press conference and said let us all talk, did you not feel the irony? You were actually initiating a dialogue, an act that belonged to the political domain.

Lt Gen Hooda: Honestly, it was the right thing to do. Whatever you might say about the military—there’s a lot of dehumanisation—we are clear about our role and responsibility. After Burhan’s killing, everybody was encouraging it—the Hurriyat took great advantage of it. I thought it was the right thing to go and say, let everyone calm down.

Barkha: Nayeema, some people think the end of the alliance was a bad thing, that it was an illustration of statesmanship and should have been given more time. Now, what is the future for mainstream parties? Parties like yours spoke one language when in alliance with the Centre. Are you going back to your calls for self-rule now? Who will believe that language?

Nayeema: The PDP lost its credibility when it went into alliance with the BJP. Perhaps we hadn’t done our homework on the psyche of our own people. We should have known what we were doing, what the repercussions would be. The experimentation done by the Indian government time and again has discredited mainstream politics in J&K. It has silenced important voices that had credibility in society and could have played a role in bringing people to a process. Yes, this was so since militancy erupted, but the confrontational attitude of the last 3-4 years has shrunk all the voices, including mainstream politicians. Because they couldn’t speak to their people.

Accept the voice of Kashmir’s elected representatives, else don’t hold elections. Also, when Omar Abdullah as CM had proposed AFSPA’s gradual removal, the Union home minister agreed, but the army shot it down. Let the security forces be directly accountable to the CM and the cabinet for each and every act.

Barkha: But look at the PDP’s response when Burhan was killed. Mehbooba Mufti took no political ownership of the decision. (Former IGP, J&K) S.M. Sahai, who knows J&K like the back of his hand, was transferred out for saying the CM was aware of Burhan’s killing. That’s how politicians leave the forces to carry the cross for them.

Nayeema: There’s a remote control in Delhi….

Chari: The first time the Modi government spoke to (anybody in Kashmir), it was former home minister Mufti Mohammed Sayeed.… But this happens every time. Parties wonder, ‘What happens to our constituency if we do this, will we be voted back to power?’

Barkha: So why can’t we reach an agreement that Kashmir should not be a 2019 poll issue? If you make J&K a national campaign issue, won’t competitive nationalism or competitive separatism destroy any space for a solution?

Chari: There’s no provision in the Constitution for (controlling) election issues. We can only make a suggestion. Even if a political party officially accepts it, and individually competition starts peaking again, there’s no point.

Banday: I think that’s the crux. Ultimately, the fundamentals of the issue are ignored when parties make it an election issue, be it the BJP, the Congress, or the PDP.

Barkha: After Burhan was killed, I was in a Srinagar hospital...there was a 14/15-year-old schoolboy, injured in an eye by pellets, and I asked what made him go and march in support of Burhan? He said Burhan was a saviour of Islam. I asked, “Aap Islam ke liye march karne gaye thhe ya azaadi ke liye? (Did you march in support of Islam or freedom?)” He said, “Dono ke liye (for both).” But Burhan’s videos, which were such a rage on social media, talk about a caliphate, right? Do separatists acknowledge this is a new concept in Kashmir, which was not there in 1989?

Gowhar: That’s a very good question. Separatists will answer that separately. I want to analyse it. I see Kashmir purely as a political issue, but with ethno-religious undertones, much like Northern Ireland. For a Kashmiri, the ethnicity of being a Kashmiri, is very important, but there is also a Muslim aspiration.

Barkha: What about Kashmiri Pandits?

Gowhar: If you see a Kashmiri Muslim and a Kashmiri Pandit on a railway platform, they hug each other and ignore people from Delhi and Punjab, because Kashmiri ethnicity takes precedence there. Yes, there is a political divergence, but Kashmiri ethnicity is very strong. When you talk about radicalisation, I agree with Gen Hooda: there’s political radicalisation, not necessarily religious radicalisation. But you can’t ignore Modi’s ascendency to power in May 2014 and the Hindutva narrative...there’s a reaction to that. The more ‘radical’ India becomes, there will be more radicalisation on the streets of Kashmir because there’s a political invasion.

Barkha: While you question Hindutva and reject it, why do you not with the same vigour reject this language that was in Zakir Musa’s and Burhan’s videos, which spoke an Islamist language not organic to J&K’s history? Yet Kashmiris are not rejecting it in the way you are rejecting Hindutva.

Basharat: What do we mean by radicalisation when we say the youth of Kashmir have become radical? Do we mean the same thing when we say we need radical reforms in banking or radical reforms in higher education?

Barkha: Obviously not.

Basharat: So what is this radicalisation? It is a normal social phenomenon—it happens.

Barkha: What we mean here is the language of a religion...the orthodoxy of a religion.

Basharat: That language is one thing, what happens or unfolds in society is a different thing. Radicalisation in Kashmir is not a cause of the conflict; it’s an effect of the conflict. The conflict did not emerge due to radicalisation. Rather, radicalisation emerged due to the conflict...it happens when parties that helm a struggle fail to achieve certain objectives. Then new parties come up, new players come up. That’s why the young people of Kashmir are questioning the Hurriyat—because the Hurriyat has not been able to deliver its promises to the people.

Now, when we read reporters who were air-dropped in Kashmir in the 1990s, we were told radicalisation was happening due to the ideology of the Jamaat-e-Islami. And when we read the Kashmir experts write about the INSurgency in 2018, we see they say Kashmiris are being radicalised by the Salafi-Wahabi ideology. This shift has also to do with how the global Islamophobic industry is working.

Barkha: And the videos?

Basharat: Yes, you mention Zakir Musa. In my study I take up two militants, Zakir Musa and Manaan Wani. Who was Zakir Musa? A day before he joined militancy, he was a ‘cool dude’, a flamboyant youngster enjoying his life in Chandigarh....

Indian policy of ‘deny’, ‘defend’, ‘defeat’, and ‘destroy’ has to change to ‘acknowledge’, ‘accept’, ‘respect’ and ‘resolve’. India should be open to third-party mediation and a Brexit-style referendum. Restore J&K’s pre-1953 status (autonomy, nomenclature of PM etc), with India retaining control in only three areas: currency, communication and defence.

Basharat: Exactly. How do we make sense of this? That an engineering student enjoying a very secular life in Chandigarh becomes a “radical” in religious terms...he is talking about caliphate, Islamic rule.

Barkha: But why are you not rejecting this language?

Basharat: I am not ‘rejecting’ it. See, I am a scholar. It’s not my prerogative to reject or accept anything. I just examine it, try to understand and solve the problem. For me, the issue has a lot to do with where you derive your legitimacy from. When the Indian Army kills any Kashmiri, where does the legitimacy come from? It comes from AFSPA, for example; it comes from the idea of securing national interests, sovereignty or territorial integrity. When militants commit an act of violence, where does the legitimacy come from? When Zakir Musa kills somebody, what will legitimise that act?

Barkha: No Indian will accept this equivalence between a terror group and the Indian military....

Basharat: I’m not asking you to accept it. It’s not an equivalence between sovereignty and religion.

Barkha: It’s nothing to do with India. No country in the world would accept it.

Chari: It’s all violence emanating entirely from the idea of Khilafat.

Basharat: Now, when we talk about development, Samuel Huntington wrote....

Barkha: Yes, there’s a clash of civilisations here.

Basharat: But Clash of Civilisations is the worst of his works. The best of his works links development with conflict resolution. The point is, you can’t stop radicalisation happening due to a political conflict by pumping in money.

Chari: There is a difference between, say, the fundamentals of science and fundamentalism in a religion. I do agree there’s a change all over the world, a new phenomenon. While working for the UN in South Sudan, I came across the phrase ‘Arabisation of Islam’. What’s happening today is extreme Arabisation of Islam, especially in non-Arab countries like Pakistan. There are Pakistani scholars who try to project themselves as part of the Arab world. Even if the Arab world tells them, ‘You are not part of the Arab world, you are not Arabs.’ This Arabisation is affecting every place. India...Kashmir is no exception.

Barkha: Do you agree that Hindutva feeds a counter, an Islamist radicalisation in Kashmir?

Chari: Again, we’re going back into clichés. What is Hindutva politics?

Basharat: What is Islamic radicalisation?

Chari: Islamic radicalisation is talking of the khilafat. Nobody here is talking about....

Basharat: Ram rajya, building a Ram temple?

Chari: Mahatma Gandhi spoke about Ram rajya. Was he a radical? Was he a Hindu fanatic?

Basharat: Think of politics as a spectrum, you place the Congress at one point, BJP at another.... I completely agree with you on what Gandhiji said about Ram rajya. In Discovery of India, Nehru said the religion of the nation is Hinduism. The BJP took it a step further...that’s what radicalisation is all about. From the Hurriyat, the militants took it a step further, Zakir Musa took it a step further.

Chari: Combine all these words and say Kashmiriyat is equal to the establishment of a khilafat. That’s when it becomes a problem.

Basharat: There’s nothing called ‘Kashmiriyat’. Barkha, you have been to Kashmir all these years, have you come across a Kashmiri equivalent of the word ‘Kashmiriyat’? It’s an empty signifier. For the BJP it’s one thing, for the Congress it’s another thing.

Chari: (to Gowhar) But you brought in Kashmiriyat. You spoke of the ethno-religious tones, and said the ethnic identity is Kashmiriyat. I don’t agree.

Barkha: I think Kashmiriyat is a construct created to evade problems.... But Kashmiris over the years admit their society is changing. Haseeb Drabu was sacked (from the PDP) for saying the issue isn’t just political, but also social. That there’s a social compact in Kashmir that’s breaking down. When the all-party delegation went to meet the Hurriyat unannounced and Syed Ali Shah Geelani shut the door, Drabu said Kashmiris don’t do that...“our society is changing”. Just like Delhi, is some moment of self-reflection needed by Kashmiri society too?

Gowhar: In the early 1990s, there was a party called Allah Tigers and a man named Air Marshal Noor Khan. They made an audacious attempt to impose a code of conduct...on how women should behave, what kind of dresses they should wear. Also, there was a ban on movie halls in Kashmir. But that was rejected by the majority of Kashmiris.

Loosely, on Kashmiriyat, I agree there’s no Kashmiri word for it, but how we used that concept is...when I was growing up, I had a Pandit friend, Upendra uncle from Rainawari in downtown. Both our families would go together to a shrine, pray together, tie ritualistic threads together. That was the kind of Sufi influence Kashmir still enjoys. Why has it taken a beating? Yes, it is social. In India, people are being lynched on suspicions of eating beef. Is that not social?

India’s decades-long pet tactics of money, muscle and ‘mainstream’ have failed miserably. You can’t stop radicalisation due to a political conflict by pumping in money. The right to self-determination has to be recognised. India holds elections, but not what is essential for a solution—a referendum.

Gowhar: When DSP Ayub Pandith was lynched, there was an overwhelming reaction against it. Nobody condoned it, everyone condemned it. There was outrage on social media, from boys and girls. Similarly, there’s so much criticism against Zakir Musa or the ISIS thing. People are calling it hooliganism. Kashmiri society is not accepting it. But why are these players becoming important? Because there’s only stuntsmanship, no statesmanship. If there’s no political intervention in Kashmir, such forces will become relevant.

Chari: He’s made an important point. We’re seeing a conscious attempt, and not only in Kashmir but all over, to suppress and if possible to erase the Sufi part of the faith. And introduce Salafism, Wahabism, whatever you want to call it. This kind of regressiveness is happening not only to Islam, it’s happening to many other religions also.

Barkha: Nayeema, we’ve had two suggestions here. One, a united administration under the Governor as an interim measure. Can India’s political parties bury petty differences for at least 8-9 months? Two, take the Kashmir issue out of election campaigns.

Nayeema: This united government...it’s an idea I don’t believe in. They’re still trying to find people ready to form a government. And that’s going to send another wrong message to the people. This regime toppling and Governor’s rule has gone on for the past seven decades. I’m not in a position to give you a suggestion on what we should do, but at least, before elections and governments, give some breathing space to the people first. They are surrounded by thousands of armed personnel.

Barkha: And not by militants?

Nayeema: According to military estimates, we have a few hundred militants. Do you think 280 militants have so much influence that they are ruling the whole state of Jammu and Kashmir?

Chari: There was only one Veerappan! The army and the police of three states were after him.

Nayeema: That’s exactly the problem with the establishment.

Barkha: Nayeema, your politics cannot change in five days of having left the BJP....

Gowhar: For me, the BJP and the PDP are a match made in heaven!

Calm on the streets must precede a solution. Disgruntled youth at the core of the agitation must be engaged and locals who joined militancy rehabilitated. Hold intra-state talks between Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh on development. Talks must include Delhi, J&K and Kashmiris, but certainly not Pakistan.

Chari: No, the UN does not define what terrorism is. In fact, India has been demanding it.

Barkha: Every country will define its sovereignty. Musharraf and Manmohan Singh accepted there was a boundary within which you have to find a solution. That there’s something that will never change...no redrawing of borders. So, if India and Pakistan de facto agree on that, what are the solutions within that? Aga, we’ve had an autonomy report of the NC, a self-rule report of the PDP...all that’s become old. What next?

Aga: That’s the problem...calling the autonomy report outdated, calling something else outdated...it’s a grave mistake Delhi is committing every day. The autonomy report was passed by a two-thirds majority by your own representative assembly. Being a third-time legislator, I want to share my first-hand experience on how we feel. Finding a scapegoat in mainstream political parties in Kashmir is what has cost India Kashmir. Finding a scapegoat for its own failures. Kashmir is a mess created by the army.

Barkha: Your partner, the Congress, failed to accept the report. How is it the fault of the army?

Aga: For the past 30 years, whenever the army has chances to capture militants alive, they prefer to kill them because they get money for that?

Barkha: The army was sent out to clean a mess created by politicians. If elections were rigged, they were rigged from Delhi. If regimes were toppled, they were toppled from Delhi. If the autonomy report was rejected, it was rejected by your political partners. How is it the army’s fault?

Aga: What happened in 2010? What was the cause of the summer unrest? The Machil fake encounter. Politicians did not conduct that encounter. Do you know the facts about Kunan Poshpora? Politicians did not do that. We have to pay for that. In Kashmir, we are symbols of New Delhi. In New Delhi, we are symbols of failure.

Barkha: Suggestions?

Aga: Accept the voice of the elected representatives, if you have faith in your own institutions. Otherwise, do not hold elections in Kashmir...call off this drama! If you only want to discredit them. Concrete suggestions? First and foremost, let the security forces be directly accountable to the chief minister and the cabinet for each and every act, which is not the case right now.

Barkha: Okay, now we have three suggestions.

Basharat: It’s worth asking, why is it that both the mainstream parties in Kashmir blame India and the army?

Aga: I will call out radicalisation too. Pakistan is taking advantage of the opportunity New Delhi presents them on a platter. That does not make Pakistan less guilty. Of fostering radicalisation.

Look at the unfortunate sequence of events that occurred due to the mistakes of New Delhi. Till the 1980s, you had to face the voice of autonomy. Because you failed that voice, you had to then face the voice of ‘freedom’, or even ‘Pakistan’. Because you failed even those moderate voices, now you have the likes of Zakir Musa. In the presence of Shujaat Bukhari, I once said this Zakir Musa might be the creation of security forces. I had this idea then. But now I find the voice of Zakir Musa finding relevance in Kashmir, and it’s because we failed the moderate voices.

Barkha: Now please do summarise, everyone, and make three concrete suggestions.

Basharat: First, India has to recognise the role of the so-called mainstream in Kashmir. When the mainstream is telling you that the army or politicians are responsible, you have to understand why they are saying so. You have given them only the municipal role...to take care of roads, water, electricity.... That’s it.

Banday: Let us not beat around the bush, let us recognise the basics and then address it. The Centre has never consistently talked, has never had the courage and the intent to carry it forward to a conclusion. Do start a dialogue process with Pakistan and the people of Kashmir. The process should be consistent, so that something emerges.

Gowhar: I think in this age of anger, there is tolerance for radical ideas. As a mature democracy, India should agree to third-party mediation much like the Northern Ireland conflict. If a Good Friday Agreement can work in Northern Ireland, why not in Kashmir? Second, take Brexit, or Scotland. That can be done in Kashmir too, with Pakistan on board.

And third, New Delhi must stop investing in three families—the Muftis, the Lones and the Abdullahs—and also stop using Kashmir as a laboratory for experiments like Hindutva or secularism or the idea of India.

Nayeema: The dialogue should start in Kashmir, with Jammu and Ladakh, much before going to Pakistan or any other agency, because there’s a lot of mistrust among the three regions. We should go for an internal dialogue. The PDP-BJP alliance was to bring all three regions together, but it has gone otherwise. And then, with the Hurriyat as well—with those senior voices that are being ignored, I don’t know why.

The pre-requisite for any solution is a profound change of perception on the ground. A talks process should start; it would pick up pace later. Also, there should be economic development sans corruption.

Barkha: Silenced voices like Shujaat’s...

Nayeema: There are so many sane voices like Shujaat, ready to contribute. The other important thing is that women have been ignored throughout these dialogues. They should be part of the dialogue process.

Aga: Don’t expect mainstream parties to represent New Delhi in Kashmir. Instead, respect the representation of Kashmir in New Delhi. At least let the governments of Kashmir be autonomous in their action.

Barkha: You mean, give them even more authority?

Aga: Yes, let security forces report to them, let the forces be accountable to governments. And start the dialogue immediately, with Kashmiris across the board, and with Pakistan. Otherwise, we will have more and more of the likes of Zakir Musa.

Prof Stobdan: We should not be looking at ‘solving’ the problem. We should look at managing the problem. Solving the Kashmir issue would require a policy, which I don’t think the country has. But managing a problem only requires certain skills. Maybe the previous generation had better skills than the current one. For example, last year there was an opportunity to make a Kashmiri, probably Farooq Abdullah, the Vice President of India. That could have bought some kind of space and time, some peace...at least for five years.

From my perspective, as a Ladakhi, this is the land of my God. Buddha was born here, hence I cannot leave this nation. Azadi is a Kashmir problem, it is not our problem. We neither accept it nor reject it.

Basharat: Patriarchy is not a woman’s problem; it is a man’s problem! Racism is never a black man’s problem; it is a white man’s problem.Caste discrimination is not a Dalit’s problem, it is a Brahmin problem.

Lt Gen Hooda: Let’s be modest, start with small steps. The first thing is to get a sense of security among Kashmiris. Everybody talks about the army being oppressive...well, voices are also silent because they are scared of the militants. Unless the State can provide some sense of security, the next step cannot be taken.

You have to bring some calm to the streets. People looking from outside Kashmir see these daily incidents, they ask, ‘Why are you talking with these people?’ That puts pressure on the government. Those images have to go away. In that sense, the ceasefire was a good thing.

She (Nayeema) talked about an intra-state dialogue. That’s critical. I’ve seen divisions between Jammu and Kashmir actually becoming much sharper. I don’t know if we can start discussing self-rule, autonomy and all (as of now).

Scale back security in towns; revoke AFSPA; gradually evolve a platform for peace through dialogue; involve Pakistan after initial progress in talks.

Barkha: Would you have extended the ceasefire, if it was your decision?

Lt Gen Hooda: I think it could have gone on for some more time. Security could still be provided to the Amarnath yatra. To me, the killings of (soldier) Aurangzeb and Shujaat was meant to trigger a breakdown of the ceasefire, and that’s exactly what they did. We should not have fallen into the trap.

Also, let’s be practical. I don’t think India-Pakistan should not talk, but to expect Pakistan to provide solutions that bring calm to the streets of Kashmir is to live in a fool’s paradise. They want the situation to simmer.

And please don’t keep demonising the army for everything. Today, among all the security forces, perhaps the Kashmiri’s best friend is the army. The police is under the state government’s control, and 90 per cent of all civilian killings are done by the police.

Chari: The elephant in the room is Pakistan. Gen Hooda is right. If you think Pakistan will find the solution, we are barking up the wrong tree. We have walked into this trap, this narrative that New Delhi’s relationship with J&K and the India-Pakistan relationship are two sides of the same coin. It is not. Dialogue with Pakistan is a different thing. Talk to their elected representatives if the non-state actors and military behave; otherwise talk to them in the language they understand. Period. Don’t mix these two issues.

Gowhar: Let’s stop this selective quoting of the UN too. If the UN designates some militant organisations as terrorist organisations, Delhi will quote the UN because it suits its own narrative. But when a UN report recognises Kashmir’s right to self-determination, Delhi will reject it.

Chari: We have heard so much about a ‘political solution’. Tell me, what better political solution can there be other than elections? Elections are a political solution.

Basharat: A plebiscite, too, is an election.

Chari: Every individual can choose a party of his or her choice. Somebody likes the PDP; fine, vote for it. Somebody likes the BJP; vote for it. The maximum number of representatives for the Congress is from Ladakh, I think. Dialogue, talks, ideas...let everything come through the ballot box.

Barkha: I think we have to close this conversation. It was a very difficult one. What we can say is that at least we spoke, and mostly we didn’t shout. Our suggestions have ranged from the practical to the philosophical. Thank you to everybody who took part.

Transcribed by Bhumika Kohli and Malavika Kodiyath

Tags