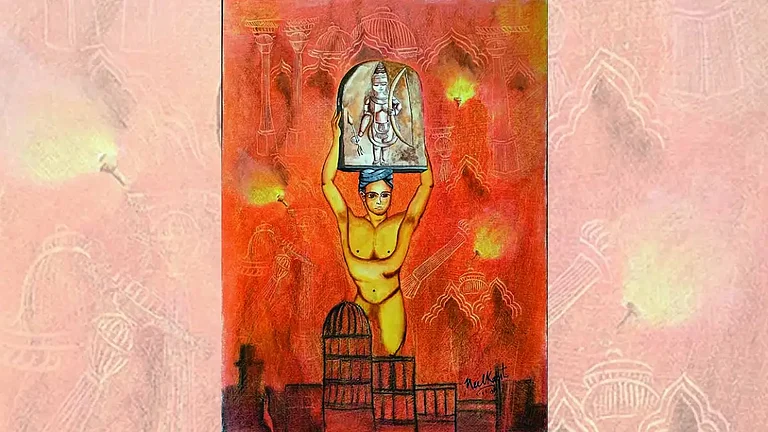

This story was published as part of Outlook's 21 October 2024 magazine issue titled 'Raavan Leela'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

The Town That Mourns Raavan

In Mandore, a desert town, the loss of a son-in-law has survived all jubilation over the narrative of good over evil. The town still mourns the killing of Raavan.

As most of northern India erupts with the thunder of firecrackers and effigies of Raavan burn down to ashes, on Dussehra, a quiet haze will descend in the historic town of Mandore in Rajasthan. Just like it always has over centuries.

Once a capital of the Marwar region, now Mandore has to make do with the modest status of being a mere suburb of Jodhpur, which had succeeded it as the capital of the Marwar princely state in the mid-15th century.

But the historic town caught in Jodhpur’s slipstream serves as an intriguing intersection, where the threads of history, mythology and culture converge, throwing up a complex but fascinating weave—one that sympathises with the demonised Lankan king, Raavan.

Inscriptions found in the town’s ancient ruins and popular memory suggest that Mandore was the home of Mandodari, the queen consort of Raavan, which effectively makes the Lankan king the town’s son in-law.

“Raavan is the son in-law of Mandore,” insists Sharwan Kumar, a local resident, who runs a small photocopying and rubber stamp store in Jodhpur. Kumar, a local mythology enthusiast, even insists that there are “historical signs” that suggest Raavan and Mandodari got married in Mandore.

According to him, the desert landscape of Rajasthan is directly connected to the Ramayana and, in many ways, to Raavan. Originally a submerged landmass, it was Ram’s Brahmastra that transformed this area into a desert, he claims.

The Valmiki Ramayana, the primary text documenting the legend of Ram, is often quoted in bits and pieces by the people of Mandore. While claims vary, the common narrative among the residents of Mandore tells of Raavan’s journey from Lanka to Mandore, where he married Mandodari after passing through a now-inaccessible cave. According to the Uttarakand of the Ramayana, Mayasur, the erstwhile ruler of Mandore and the father of Mandodari, arranged their marriage and Mandodari’s unwavering devotion to Raavan, even after Sita’s abduction, contributed to Raavan’s eventual demise at Ram’s hands.

One of the most intriguing tangible connections to Raavan in Mandore is the modest temple dedicated to him, located behind a grand Shiva temple. Here, amidst lush greenery, a statue of Raavan is venerated by the Dave Brahmin community.

While Raavan is often seen as the villain in the Ramayana and in Indian popular culture, families like the Mudgals and Daves revere him as an ancestor and a learned figure skilled of Vedic knowledge, astrology and music. Kamlesh Kumar Dave, a priest at the Mandore temple dedicated to Raavan, claims the eventually slayed Lankan king is an ancestor of the Dave clan. The clan still continues to perform rituals honouring his demise, even collecting remnants of his burnt effigies for cremation.

Raavan is a figure marked by endless complexity. Described as a master of the Vedas, an accomplished musician and an unparalleled warrior, his legacy extends far beyond his role as Sita’s abductor. According to legend, Raavan was an extraordinary scholar, skilled at playing the veena and capable of commanding the elements through his knowledge of mantras. His wisdom is believed to have been so profound, that an impressed Lord Brahma himself visited Lanka to learn from him.

Yet, his pride—counterbalancing his vast intellect—eventually led to his downfall. Raavan’s ties to Mandore, his marriage to Mandodari and the defeat by Ram make him a tragic figure in the region’s identity.

Under clear skies and bright sunlight, the dusty Marwar land reveals a spot known as “Raavan Ki Chanwari”, located just behind Mandore railway station. Steep steps lead to a clearing featuring rock engravings believed by local residents to depict Raavan’s marriage. According to legend, this is where Raavan and Mandodari exchanged wedding vows. Now, a government board designates the area as a protected site.

For the faithful, the search for Raavan might end here, but for the adventurous, Mandore offers even more. A winding road leads out of town, where houses give way to rocky terrain and harsh landscapes. As the sun sets, one feels transported back in time, where myths and folklore seem to infuse the rocks and sand. Known locally as ‘‘Nagadhadi’’, this area is believed to have once been submerged under water, transformed by Ram’s Brahmastra. The road culminates at a crater-like lake, with a steady stream of water cutting through a gorge amid the hills. Visible signs of water erosion on the rocks can be spotted, hinting at the area’s ancient past, according to a local guide.

Does Mandore withstand the scrutiny of the logical and the sceptical? Do any myths, for that matter? The charm of this quaint town is rooted in its ability to defy logic. In a contemporary climate where natural phenomena are often twisted to validate the contents of religious texts like the Ramayana, Mandore’s allure stems from the town and its people not insisting on an alternate reality as the only one. But perhaps, what is more significant is that the historic town and its people avoid bundling science and history to make a point, preserving its myths and folklore in their purest, and unblemished form.

(This appeared in the print as 'Dunes of Grief')