A small well-kept secret—about an X-ray of a pair of human lungs—had played a large part in the partition of India.

What If We Were Together?

The Partition was a tragedy, but the greater tragedy is that today the dream of a united India is the fantasy of the fanatics. I have been party to a fantasy of this sort myself...

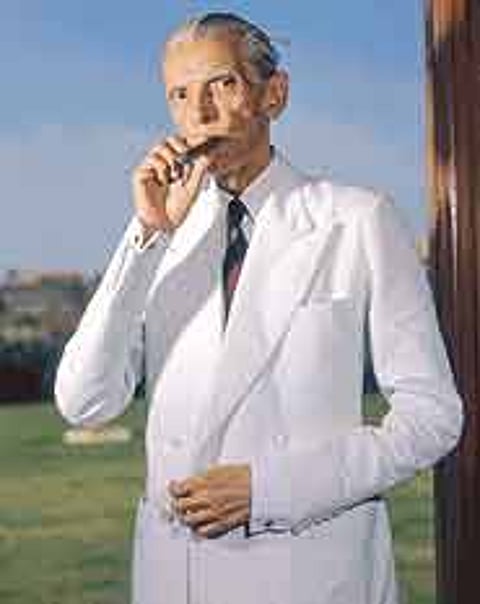

The X-ray had been made in June 1946. It showed two dark circles surrounded by an irregular white border—proof that the patient was suffering from severe tuberculosis and did not have long to live. The pair of lungs in that X-ray belonged to Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

In the book Freedom at Midnight, Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre write that if Louis Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru or Mahatma Gandhi had been aware in April 1947 of Jinnah’s illness, "the division threatening India might have been avoided."

The story about the X-ray—and stretching behind it, a view of history where chance has greater consequences than anything else—blurs the line between fact and fantasy. Its appeal lies in its ability to tease the past with another, tantalising possibility. But, in this case, the possibility is one that exercises a powerful hold on our imagination. What if the partition of India hadn’t taken place?

The subcontinent would not have witnessed what has been described as the largest exodus in recorded history—the forced migration of 17 million or more—and we would have been spared the fury of a communal holocaust, the killings and rape and abduction of hundreds of thousands of innocents.

We would not then have had our literature of the riots. Saadat Hasan Manto would’ve remained an obscure, alcoholic scriptwriter who wouldn’t create Toba Tek Singh, who doesn’t know whether he belongs in India or Pakistan. Ritwik Ghatak might still have made masterpieces like Meghe Dhaka Tara but there would not ever be in such films the bitterness of uprooting and loss. No matter. Nothing that Manto or Ghatak did—and not a single sentence penned by Amrita Pritam, Bhisham Sahni, Jibanananda Das, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Intizar Hussain, and others—can console us for the terrible brutality that became the benchmark for all the violence that we have unleashed on each other since then as a free people.

Historians Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal write that "India’s federal dilemma, the threats to its secular ideology, the class, caste and communal conflicts and, above all, military disputes with Pakistan, are all directly related to the decisions of expediency taken in 1947." A united India would certainly have worked only as a confederation or a loose federation. In the bargains struck over the Partition, the Congress claimed for itself the unitary centre in Delhi and power over three-fourths of India. In the following decades, the ruling elite could rely on the anxieties bred by the Partition to forge a hegemonic centralist policy that was responsible in part for the rise of separatist movements in various peripheral states.

The point is not simply that an undivided India would have allowed us a history sans the wars that have plagued our past. One must go further and contemplate the thought that in a polity that was a federation with established autonomy for its members, the bloodshed we have seen in states like Punjab, Assam, and Kashmir could also have been avoided.

The Partition sanctioned a nationalist paranoia about borders, about migration across our boundaries, and legitimised a profound suspicion of minorities. While reservations for the so-called backward castes was a matter of national debate as well as active implementation, the idea of protecting the rights of religious minorities in India was buried under the rhetoric of appeasement. With reservation for Muslims, Laloo Yadav could have entered into an alliance with Nawaz Sharif—and the Pakistanis might have become our allies in the fodder scam long before they became partners with us in match-fixing.

It galls many Pakistanis to hear Indians talk of the Partition with regret.But, if the Partition hadn’t occurred, Pakistan would not have been trapped in an identity crisis, trying vainly to produce for itself an Arab history and a pure Islamic identity. Similarly, if we didn’t have behind us the history of the Partition, parties like the BJP would not have gone about so systematically purging our history books and even our language of the traces of a long coexistence with Islam.

Indeed, an undivided India would have been an unwieldy polity. But we would not at least be championing nuclear war. India would still be home to a million mutinies, but it would be very difficult for our leaders to dismiss any protest as terrorism. There would still be religious divisions. But it would have been impossible to undertake with such insolent impunity the demolition of the Babri mosque.

The Partition was a tragedy, but the greater tragedy is that today the dream of a united India is the fantasy of the fanatics. In Pakistan, Maulana Masood Azhar, the leader of the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, declares that he will be a modern Bin Qasim: "Allah has sent me here, and if you cast an evil eye towards my beloved country, I will enter India with 500,000 of my mujahideen, inshallah." In many Indian schools where the syllabi reveal a saffron bias, writes Nalini Taneja, the map of India "is shown as including not only Pakistan and Bangladesh but also Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet and even parts of Myanmar."

I have been party to a fantasy of this sort myself. All through my adolescence I had wanted to undo the Partition, not because I wanted to reverse the tragedies of 1947—no, I wanted the Partition to have never taken place because I had seen visions of an invincible, united India, marching into battle at Lord’s under the same colours. Gavaskar and Imran, Kapil and Miandad, Tendulkar and Akram....

Even our ordinary pleasures have been blighted by a new, popular kind of hypernationalism in the last few years. I was reminded of this recently when minutes after the Indian victory in a one-day match against Pakistan last March, my teenage nephew excitedly sent this SMS to me: Pakistan ko sharaafat sikha diya, Hindustan ki takat dikha diya, Sun le Musharraf, Kashmir to kyaa, Karachi mein bhi aaj tiranga lehra diya. (We have taught Pakistan how to behave, we have shown India’s strength. Listen Musharraf, forget Kashmir, we have planted the tricolour even in Karachi.)

Amitava Kumar is the author of Husband of a Fanatic, published this month by Penguin-India.

Inchon 1950: What if Macarthur’s brave port assault had failed, would all of Korea be communist?

Dublin 1922: What if Michael Collins had refused partial Irish freedom? Would Ireland be united?

Tags