A Rajasthani-Irish collab Citadels of the Sun after Mehrangarh fort will hop to Grianán of Aileach fort in Donegal. Two Padma Shri vocalists: Lakha Khan on the Sindhi sarangi will sing Meera bhajans, Sufi kalaams, Hindi tunes, and Anwar Khan Baiya will sing Meera, Kabir, Dadu, and Gorakhnath bhajans. Arifa from Amsterdam stirs in Balkan and Middle Eastern sounds, in a fusion with Manganiar and Langa khartal and dholak master musicians. An interactive session with indigenous Khasi musicians, who are academicians pursuing a PhD. A dance bootcamp of Ghoomar and Kalbeliya and a performance by Agni Bhawai, a Rajasthani fire eating and dance performance. A bevy of women headliners: Jagran exponent Sumitra Devi, Mohini Devi of the Jogi Kalbeliya tradition, and Suraiya ji of rajwadi mand Hindustani music genre...

Why 2022 Jodhpur RIFF Is A Beacon Of Hope For Rajasthani Folk Musicians

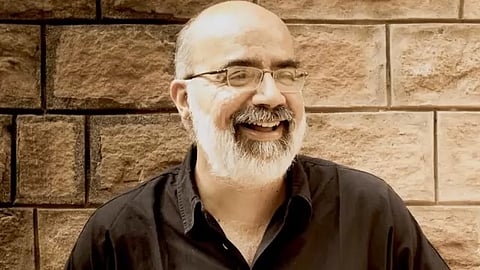

A dynamic festival director and a series of year-long initiatives is what makes the Rajasthani International Folk Festival (RIFF) more than its four-day event for tourists and lovers of folk music.

These highly versatile sounds are only a speck in the extensive programming at the 13th edition of the four-day Rajasthani International Folk Festival (RIFF), packing in 250 artists. RIFF, timed around Sharad Purnima when the full moon will dawn on the Mehrangarh fort named after the sun. The line-up, despite a two-year interlude courtesy of the pandemic, is quite ambitious. As always, the maverick who stitched it together is Divya Bhatia, festival director of RIFF with Maharaja Gaj Singh II of Marwar-Jodhpur as India's patron and Mick Jagger, The Rolling Stones’ frontman, as an international patron.

“From Jodhpur, I’ll head to London, then Mauritius, back to Jodhpur, then Portugal, then Oman, Muscat, come back, then Morrocco, then Columbia...before November. I travel the world to see music. This year, I watched 18 bands play in South Korea. I watch anywhere from 200-300 bands in ‘lighter’, years, and 8-900 bands in ‘heavier’ years. I can tell you my dates, schedules… it’s all in my head. Maybe, I remember because I have no time for gossip, all my work is my life, and I don’t think in silos,” he adds.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Bhatia is adept in tabla, sarangi, bongo, conga, and box; can speak in German, Spanish, and Italian; acted in The Dilemma a Motley production by Naseeruddin Shah; headed Prithvi Theatre Festival, Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, Aadyam Theatre; starred in films Delhi Belly, Talvar, Ship of Theseus and Badlapur; arranged music for Ambani, Kirloskar, Tata, and Jindal weddings, and is visiting faculty for Applied Theatre at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, London. Jodhpur RIFF, he says, was just en route to his personal trajectory. He fell in love with folk music as a child after discovering the hour-long weekday slot reserved for the genre on All India Radio. In his theatre days, he became engrossed with actor-audience dynamics. Not a fan of classroom learning, he says these varied life experiences came into use when he came onboard RIFF in 2007.

Local musicians in RIFF’s programming are largely the Manganiars and Langas, both Dalit communities under centuries-old subjugation by their jajamans (sarvana/upper caste benefactors), and are embroiled in casteist battles in Jodhpur. Many of them are landless, some have become labourers, and senior musicians, especially, are out of work. Some own small homestays or hotels, and others performed for Jagrans (all-night vigils) and weddings, but pandemic these activities to a halt. The government, he says, in the race to urbanise, has looked after indigenous craftsmen, but forgotten its traditional folk artists. Through music, revival, and rehabilitation initiatives, RIFF is trying to change its fortunes, and continue to offer platforms to folk musicians outside Rajasthan.

Like its Citadels of Sun, where handpicked Rajasthani musicians performed at Grianan of Aileach fort in Ireland, and Irish musicians performed at the Mehrangarh Fort in 2019. At this RIFF edition, the joint performance would chronicle a day's trajectory from dawn to dusk. “All root traditions in the world follow the lunar calendar for its advice on the new harvesting cycle. Eid is based on the Lunar calendar, and even our tithis (important dates). How then do you create a modern-day festival that folk artists can feel is their own?” Answer: time it around the auspicious day of Sharad Purnima, which marks the beginning of harvest, the onset of winter, a time change, and to start afresh. “It’s the brightest full moon that slowly rises behind the artiste on the main stage. The concert schedule is designed the ensure the audience is outdoors during sunrise, sunset, moonrise, etc.,” says Bhatia.

During the pandemic, RIFF collaborated with the British Council and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture to organise a Rajasthani roots gig called Classic Bagh Festival on the lawns of Delhi’s Sunder Nursery amphitheatre to raise the morale of the 50 folk musicians who performed. Its year-long fundraising initiative managed to support close to 2,000 artists and their families across 60 villages in Rajasthan. “We identified the very needy families, contact a shop in their locality and transfer them the required money to make food kits, and have locals distribute these,” says Bhatia.

A festival highlight is the premiere of RIFF’s incubated band called SAZ, after the initials of its bandmates and Langa musicians, Sadiq, Asin, and Zakir, which is also a first-ever indie music gig in the festival. How does Indie music fit into roots? “Every music genre has roots. I can have a history of electronic or contemporary music. But what are their roots? Roots are about lineage and connection, not history.” SAZ however began from a failed song-writing experience.

In Rajasthani folk music ethos, almost no new songs are being written. "As an experiment, we had a group of Rajasthani contemporary poets interact with master musicians, hoping the latter would compose the contemporary lyrics into their songs. But they were put off by the negativity. They said yes, trees are getting cut, but do I have to sing it in a song and tell you that? I would rather sing about the beauty of the bird in the tree so you realise that it’s missing when the tree is gone. They felt contemporary lyrics were always about the ‘I’, ‘what I think is right’. Our poetry is never about ‘I’, always about ‘us’, and written in beautiful poetry. That’s how SAZ was formed, keeping the old ethos in mind, along with new lyrics,” informs Bhatia.

But some old traditions, are best, be gone. Like the purdah (veil) system that frowns upon women giving a song or dance recital in front of men. “Interestingly, a lot of these traditional artists learned to sing from their mothers. The mothers know all the lyrics, and their fathers, present and play instruments. We are slowly encouraging the women to perform,” says Bhatia, pointing to the two opening acts and other women-anchored acts in the line-up.

Among the year-round initiatives, is a guru-shikshya model. For two months now, seven master musicians, between 30 to 70 years of age, are giving paid music lessons in their homes to about 35-40 youngsters in the vicinity. If this pilot model is successful, RIFF will raise funds and construct a bigger model where students will get the chance to perform at public venues. Another initiative is a living music museum having an instrument library and workshops at the Mehrangarh Fort Museum. The making costs of indigenous stringed instruments sarangi and kamaicha are close to Rs 25,000, proving steep for artisans. Twelve commissioned kamaichas and sarangis are already underway.

Tags